Friday Sermon Sultan Ḥadīth Query

Question

Many Imams refer to a Sultan in their Friday sermons and mention the following sentence or something similar:

من أھان سلطان اللہ في الأرض أھانه اللہ

Is there any basis for this and what does it mean? Is it permissible to cite this narration when the Muslims do not have a Sultan?

Read the answer below or click on the following link for the PDF version: Friday Sermon Sultan Hadith Query

بسم اللہ الرحمن الرحیم

Answer

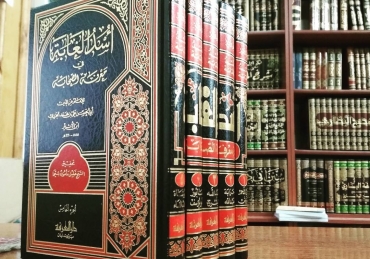

Ziyād ibn Kusayb al-ʿAdawī (n.d.) narrates: I was with Abū Bakrah [may Allah be pleased wih him, d. 51-2/671-2] under the pulpit of [ʿAbd Allah] Ibn ʿĀmir [may Allah be pleased wih him, d. 59/678-9] while he was delivering a sermon wearing a fine garment. Abū Bilāl[1] said: “Look at our Amīr wearing clothes of sinners.” So Abū Bakrah said: Be quiet. I heard the Messenger of Allah ﷺ saying: “Whoever insults Allah’s Sultan on the earth, Allah disgraces him.” This narration has been transmitted in many ḥadīth books.[2] Imām Tirmidhī (d. 279/892) has classified this narration as ḥasan (agreeable). The great master of ḥadīth sciences Ḥāfiẓ Mizzī (d. 742/1341) concurs with this.[3] Accordingly, there is no harm in narrating this in the Friday sermon.

ʿAllāmah Ṭībī (d. 743/1342) explains that the term ‘Allah’s Sultan’ has been used to indicate the status of the Sultan and the respect he deserves, similar to the term ‘House of Allah’.[4] Ḥāfiẓ Suyūṭī (d. 911/505) explains that this is because Allah has appointed the Sultan to execute his commands. Therefore, to respect the Sultan is to honour the position and the honorific role bestowed on him by Allah. He further adds that insulting the Imam includes disobeying his commands in matters of virtue.[5] ʿAllāmah Munāwī (d. 1031/1622) further elaborates and suggests that the complete system of religion cannot be attained except through an Imam who is obeyed. Thus, the Sultan is the protector and guardian of the faith, whose absence would result in killings, trials, tribulations, and a collapse of religious and social systems and structures.[6] There are many narrations that affirm the importance of obeying the leader. The Prophet ﷺ said, “You should listen to and obey your ruler even if he was an Ethiopian slave whose head looks like a raisin.”[7]

It is worth noting that some versions of the narration include the words: “The Sultan is the shade of Allah.”[8] Other narrations include the words: “The Imam is the shade of Allah on earth.” Ḥāfiẓ Haythamī (d. 807/1405) suggests that this has been narrated by Imam Aḥmad (d. 241/855) and that the narrators of his chain are trustworthy.[9] The Sultan has been described as the shade of Allah because his role is to prevent harm and protect the wellbeing and welfare of the people similar to how the shade protects a person from the heat and rays of the sun. People seek redemption in the shade of his justice from the heat of oppression. Thus, this status is for the Sultan who champions justice and implements the commands of Almighty Allah and fulfils his rights and the rights of his servants. Otherwise, the Sultan will be a shade of his personal desires and whims. The role of the Sultan is to establish faith, adhere to and implement divine laws and establish a just rule.[10] The Prophet g said in another narration, “Verily, the Sultan is the shade of Allah on earth. The servants of Allah seek shelter in him. If he does justice, his due is reward and the due of the people is gratitude. If he is oppressive, his due is sin and the due of the people is patience.”[11]

Finally, is it relevant to narrate the aforementioned narration considering that the Muslims do not currently possess a unified leadership? The answer to this is twofold:

Firstly, the Qurʾānic verses and prophetic narrations are relevant, beneficial and applicable until the final hour. Many Islamic teachings for example in relation to the criminal justice system are not currently practiced; however, they are taught and discussed as they are relevant and remain applicable until the final hour.

Secondly, the absence of a unified Muslim leadership makes it all the more important to transmit relevant narrations regarding leadership so that Muslims are reminded of their communal obligation to appoint a leader and establish a unified just rule in accordance with divine laws. Shāh Walī Allāh Dehlawī al-Ḥanafī (d. 1176/1762) writes, “It is a communal obligation on the Muslims until the day of judgement to appoint a Caliph who fulfils the criteria of caliphate.”[12] Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymiyah al-Ḥanbalī (d. 728/1328) explains that this is one of the greatest obligations without which Islam cannot be complete.[13] Similarly, Imam Abū ʿAbd Allah al-Qurṭubī al-Mālikī (d. 671/1273) writes, “This verse is the basis for the appointment of the Imam and the caliph who is listened to and obeyed, so that the words [of Muslims] can unite through him and the rules of the caliph can be implemented through him. There is no difference of opinion among the Ummah or the Imams regarding the obligation of this.”[14] Similarly, Imam Nawawī al-Shāfiʿī (d. 676/1277) writes, “The scholars are unanimous that it is necessary on the Muslims to appoint a caliph.”[15] There are many misconceptions about a unified Muslim rule. However, at the heart of a unified Muslim rule is a federal structure underpinned by universal values of justice, social action, human rights, rule of law and equality. Under the unified Muslim leadership over the past fourteen centuries, those who did not share our faith were granted protection and the Muslim world was more safe, prosperous and peaceful.

In conclusion, there is no harm in Imams transmitting the aforementioned narration, though it is not necessary. May Almighty Allah shower his mercy on the Ummah and grant us leaders who can bring about peace and prosperity all over the world.

Allah knows best

Yusuf Shabbir

2 Ramaḍān 1437 / 7 June 2016

Footnotes

[1] Mullā ʿAlī al-Qārī (d. 1014/1605) suggests in Mirqāt al-Mafātīḥ (6: 2407) that perhaps Abū Bilāl refers to Abū Burdah ibn Abī Musā al-Ashʿarī (d. 103-4/721-3). Shaykh ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Mubārakpūrī (d. 1353/1935) concurs with this in Tuḥfat al-Aḥwadhī (6: 394). This is theoretically possible because Abū Burdah was over eighty years old when he passed away, as mentioned in Siyar (4: 343). However, Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī (d. 748/1348) suggests in Siyar (3: 20; 14: 508) that this is referring to the Kharijite Abū Bilāl Mirdās ibn Udayyah (d. 61/680-1). This is also the view of Ḥāfiẓ Mizzī (d. 742/1341) (see footnotes of Tahdhīb al-Kamāl, 7: 399) and ʿAllāmah Ibn al-Athīr (d. 630/1233) in al-Kāmil (3: 110). This is the correct view as it is highly unlikely that someone like Abū Burdah would make such negative comments regarding the companion ʿAbd Allah ibn ʿĀmir (may Allah be pleased with him, d. 59/678-9).

[2] Sunan al-Tirmidhī (2224); Musnad Abī Dāwūd al-Ṭayālisī (928), Musnad Aḥmad (20433); al-Sunnah of Ibn Abī ʿĀṣim (1017), Musnad al-Bazzār (3670), al-Thiqāt (4: 259); al-Sunan al-Kubrā (16659).

[3] Tahdhīb al-Kamāl (7: 399).

[4] Al-Kāshif ʿan Ḥaqāʾiq al-Sunan (8: 2576).

[5] Qūt al-Mugtadhī (2: 535). Also see Mirqāt al-Mafātīh (6: 2407).

[6] Fayḍ al-Qadīr (4: 142).

[7] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī (7142).

[8] Al-Sunnah of Ibn Abī ʿĀṣim (1024); Shuʿāb al-Īmān (6988).

[9] Majmaʿ al-Zawāʾid (5: 215).

[10] Al-Nihāyah fī Garīb al-Ḥadīth wa al-Athar (3: 160); Sharḥ al-Nawawī ʿalā Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim (16: 123); Lisān al-ʿArab (11: 419); al-Fatāwā al-Kubrā (5: 123); al-Kāshif ʿan Ḥaqāʾiq al-Sunan (8: 2587); Mirqāt al-Mafātīḥ (6: 2419); Fayḍ al-Qadīr (4: 142).

[11] Al-Amwāl of Ibn Zanjawayh (32); Musnad al-Bazzār (5383); Fawāʾid Tammām (502); Shuʿab al-Īmān (6984); Tārikh Baghdad (17: 72). This narration is weak as mentioned by Imām Bayhaqī (d. 458/1066), ʿAllāmah ʿIrāqī (d. 806/1404) in al-Mugnī (1: 1441) and ʿAllāmah Haythamī (d. 807/1405) in Majmaʿ al-Zawāʾid (5: 196). Ḥāfiẓ Mundhirī (d. 656/1258) is also inclined towards this in al-Targhīb aa al-Tarhīb (3: 118). However, Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymiyah (d. 728/1328) suggests in al-Fatāwā al-Kubrā (5: 123) that the [meaning] of this narration is ṣaḥīḥ (sound).

[12] Izālah al-Khafāʾ ʿan Khilāfat al-Khulafāʾ (1: 88).

[13] Al-Siyāsat al-Sharʿiyyah (p. 129).

[14] Tafsīr al-Qurṭubī (1: 264).

[15] Sharḥ Muslim (12: 205).

Who are the leaders of the youth in Paradise: Abu Sufyan or Hasan and Husayn