Seven Days in Bukhara and Samarqand with Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani (b. 1362/1943) and Mufti Shabbir Ahmed (b. 1376/1957)

This page will be updated regularly, scroll to the bottom to read the latest daily updates.

In the name of Allah, the Compassionate the Merciful

Day 1 – Saturday 13 April 2019

Arrival into Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Introduction

Four days ago, I woke up to a phone call from our respected Shaykh al-Islām Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani explaining that he is currently in Moscow with plans to travel to Bukhara (Uzbekistan) on Sunday, adding that I should consider joining him. It was only less than three weeks ago that Mufti Ṣāḥib survived an assassination attempt. Clearly, this had not deterred him from continuing his travels both in Pakistan and beyond. May Allah Almighty keep his shadow over us for long.

Last year, I was fortunate to travel with him in the Balkans and most recently seven weeks ago, I spent some time with him in the blessed city of Madīnah in Saudi Arabia. Spending time in the company of scholars such as Mufti Ṣāḥib provides a unique opportunity to benefit from and tap into an ocean of knowledge and wisdom. This combined with the fact that I had always had a strong desire and intention to visit this region which was once the centre of Islamic knowledge and home to thousands of scholars. Our legacy, tradition and history are entrenched with this region, and there could not be a better opportunity to appreciate this than by travelling with Mufti Ṣāḥib.

Therefore, along with my parents, we leave from London Heathrow on Friday 12 April 2019 on the 9.35pm Uzbekistan Airways direct flight to Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan.

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan is a Central Asian nation and former Soviet republic. It is known for its mosques, mausoleums and other sites linked to the Silk Road, the ancient trade route between China and the Mediterranean. Its population is 33 million with the Muslim population exceeding 90%. It is home to cities which have both modern and medieval economic and cultural significance. They include: Tashkent, Samarqand, Bukhara, Termez, Fergana, Namangan and Andijan. The country is sandwiched between and landlocked by five ‘stan’ countries: Kazakhstan to the north, Kyrgyzstan to the northeast, Tajikistan to the southeast, Afghanistan to the south and Turkmenistan to the southwest.

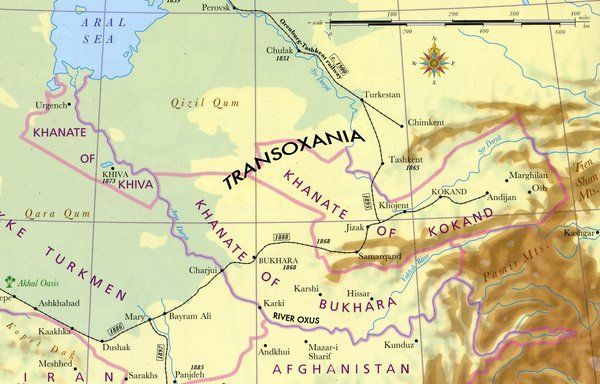

Mā Warāʾ Al-Nahr

Uzbekistan is part of the region known as mā warāʾ al-nahr, which literally translates as what is beyond the river, a reference to Transoxiana, the region beyond the Oxus river. This term is commonly used in fiqh books and many senior ḥanafī jurists lived in this region. Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Southern Kyrgyzstan and southwest Kazakhstan are part of Transoxiana.

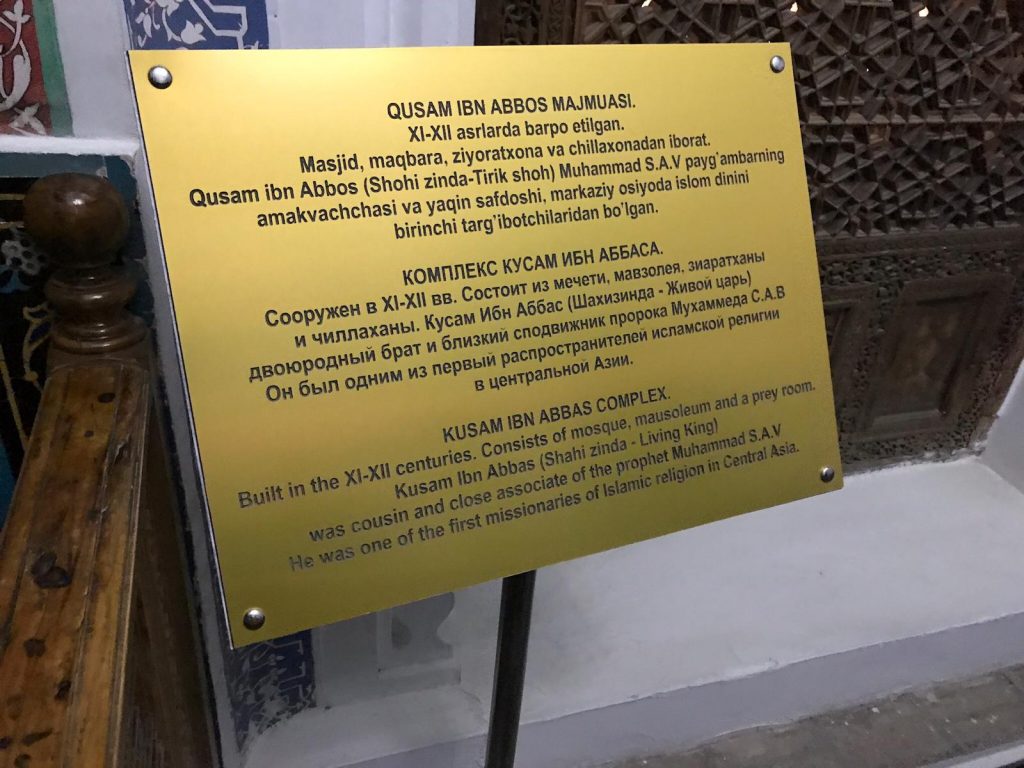

Part of this region was conquered by Qutaybah ibn Muslim (d. 96/715) between 706 and 715 CE and loosely held by the Umayyads from 715 to 738. The conquest was consolidated by Naṣr ibn Sayyār (d. 131/748) between 738 and 740 CE, and continued under the control of the Umayyads until 750, when it was replaced by the Abbasids. However, prior to all this, the companion Qutham ibn al-ʿAbbās (d. 57/676-7, may Allah be pleased with him) was among the first group of Muslims to begin the conquest of this region under the leadership of Saʿīd ibn ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān (d.ca. 62/682) in the era of Muʿāwiyah (d. 60/680, may Allah be pleased with him). He was martyred in Samarqand. It is understood that he is the only companion to have passed away in Uzbekistan, which makes him the final companion to have passed away here.

Tashkent (Shāsh)

We descend into Tashkent International Airport at 8.35am. Friendly staff greet us at the Airport and the immigration process is swiftly conducted. From 1st Feb 2019, British passport holders do not require visa and there is no entry fee. Within 15-20 minutes, we are on our way out of the Airport.

We are warmly received by our respected Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani’s host, Shaykh Fozil (pronouncd as fāḍil) Kayumov, who takes us to our hotel. The temperature is moderate, about twenty degrees. Shaykh Fozil graduated from the famous Mahad al-Fath al-Islami, Damascus, Syria in 2009. He is part of the management of Dar al-Hilal (Hilol Nashr) organisation which specialises in publishing Islamic books in Uzbek and Russian languages.

After resting a short while, we begin touring Tashkent with Shaykh Fozil. Tashkent is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan, located in the north-east of the country. It is one of the most populated cities in ex-Soviet Central Asia. In 2018, its population was approximately 2.5 million. It currently has 130 mosques. In previous times, this city was known as Shāsh. Shāsh means stone. Tashkent (pronounced in Arabic as Ṭashqand) means the city of the stone, as Qand means city and Ṭash means stone. The name was changed several hundred years ago. The author of the famous ḥanafī text on uṣūl al-fiqh, Uṣūl al-Shāshī, which is taught as part of the niẓāmī syllabus, originated from here. It is not known with certainty who the author of the text is. Suggestions include: Abu Yaʿqūb Isḥāq ibn Ibrāhīm al-Shāshī (d. 325/936), Abu ʿAli Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Isḥāq al-Shāshī (d. 344/955), Niẓām al-Dīn al-Shāshī (7th/13th century) among others. Perhaps, the most famous scholar of this city is the famous Shāfiʿī jurist, Imam Abū Bakr Qaffāl al-Shāshī (d. 365/976), we hope to visit his tomb later in the trip. What is interesting is that the famous geographer Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī (d. 622/1225) mentions in Muʿjam al-Buldān (3:308) that the inhabitants of Shāsh are shāfiʿīs despite the rest of this region being dominated by ḥanafīs, attributing this to Imam Qaffāl who studied the shāfiʿī fiqh outside this region and returned to the city. Today, however, this city like the vast majority of this region is predominantly ḥanafī and there is not a single shafiʿī. This ‘dictionary of countries’ (Muʿjam al-Buldān) of Yāqūt is an incredible book in alphabetical order containing geographic descriptions for most of the Muslim world, supplemented with historical, ethnographic, and associated narrative material. It is a very useful primary source. Some parts of the Muslim world such as the Balkans is not mentioned therein as it was conquered by the Ottomans after the era of Yāqūt.

Dar al-Hilal (Hilol Nashr)

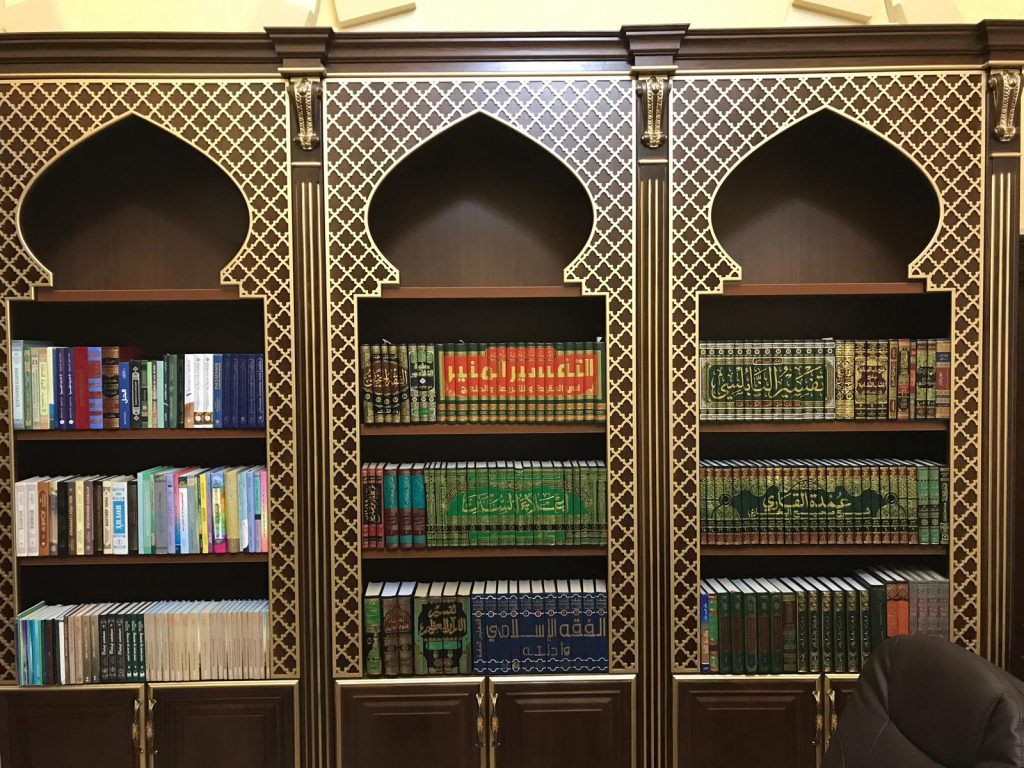

Our first stop is the Headquarters of Dar al-Hilal (Hilol Nashr) where we arrive shortly after Ẓuhr Ṣalāh. The organisation specialises in printing, publishing and selling Islamic books with a particular emphasis on the Uzbek language as well as Russian, the second official language of the country. The revolutionary work of organisations like Dar al-Hilal must be understood in light of the recent history of the country which was subject to more than seventy years of communism. Religious restrictions continued after Soviet rule ended and the remnants and effects of the dark age continue to date. Since the appointment of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev in December 2016, many religious restrictions have been lifted and there is an increase in Islamic activity. Unlike before, there are no restrictions on visiting Masjids for Ṣalāh and the rules pertaining to the headscarf and beards are being relaxed, although some complications remain. Last year, the headscarf was banned in schools and universities, however, today an announcement has been made providing flexibility.

It is in this context that a great scholar by the name of Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq ibn Muḥammad Yūsuf (d. 2015/1436) founded Dar al-Hilal in 2011 with a sole focus on spreading Islamic knowledge. The first book published by the Dar was the first volume of the Uzbek translation of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī.

Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq ibn Muḥammad Yūsuf

We are welcomed at the organisation’s Headquarters by Shaykh Muḥammad’s son, who currently presides over it, Shaykh Muḥammad Ismāʿīl, who completed his Islamic studies in Libya. He and Shaykh Fozil introduce us to the organisation and give us a tour of the books published by them which include a range of translations with a particular emphasis on the works Shaykh Muḥamamd al-Ṣādiq.

Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq was born in Andijan on 21 Rajab 1371, corresponding to 15 April 1952. He acquired his early education with his father Shaykh Muḥammad Yūsuf and others and later joined the Mir-i-Arab Madrasah in Bukhara. Thereafter, he studied at the Maʿhad al-Imam al-Bukhārī in Tashkent and travelled to Libya to further his Islamic studies. After graduating in 1980, he returned to Uzbekistan. He served in various religious and political roles until 1993 when he was forced to leave the country. After spending a year in Saudi Arabia and several years in Libya, he returned home in 2001. He served in various global Muslim organisations and wrote many books in Uzbek. They include the translation of the Qurʾān with brief commentary, translation of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, commentary of al-Adab al-Mufrad, al-Kifāyah (a three-volume commentary of the ḥanafī fiqh manual wiqāyah) and a nine-volume collection of his Fatāwā of which seven volumes are published. He authored more than 125 books on a range of topics. Dar al-Hilal has published many of these and is working on publishing the remainder. His books are available online and also on Apps. Train passengers across the country are able to access and read these books for free on their devices and there are ongoing discussions to provide a similar service to the passengers of Uzbekistan Airways. The Tafsīr al-Hilāl authored by Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq in six volumes is the first complete tafsīr in modern Uzbek. Similar to Turkey, tafsīrs exist in Uzbek from earlier times, however, they are written in Arabic/Persian script, which is alien to the vast majority of Uzbeks.

The setup at Dar al-Hilal is impressive and very professional. An in-house printing department prints books to a very high standard. There are nine branches in the country that sell the books they print as well as other books, three in Tashkent and the remaining in other provinces. There is also a branch in Moscow, Russia and one in Osh, Kyrgyzstan, and one in Seoul, South Korea. The reason for opening a branch in South Korea is that there are more than 3000 Uzbek nationals studying and working there. Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq also succeeded in appointing an Imam for these people and a Masjid was also established in South Korea to serve their needs.

After listening to Shaykh Muḥammad Ismāʿīl and his colleagues, my respected father Mufti Shabbir Ahmed comments that Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq revived the dīn in this area and deserves the title of mujaddid of Uzbekistan. He like his father were linked to the naqshbandī sufi order, the prevalent order in this region. In 2015/1436, Shaykh passed away after suffering a heart attack. A beautiful complex has recently been built in his name ‘Masjid Sheikh Muhammad Sadik Muhammad Yusuf’ which comprises of a Masjid, library, museum and a women’s facility. It has not been inaugurated yet. Generally, in this region, women do not attend Masjids for prayers and most do not have facilities. This is perhaps an example of the region’s influence on the fiqh of the Indian sub-continent.

We take leave from Dar al-Hilal and continue our tour of Tashkent. The city is well established with modern infrastructure. The skyline is dominated with Masjids, and under the presidency of the current President, many new Masjids are being built and old ones renovated. Shaykh Fodel explains that the majority of scholars of the country completed their studies in Pakistan, Libya, Syria or Egypt and many Uzbek students are now benefiting from Syrian scholars based in Istanbul. Shaykh Fodel and his colleagues hosted Shaykh Muḥammad ʿAwwāmah (b. 1358/1940) last year. The government also enjoys a good relationship with the current Turkish government, this is positive.

Hadiqotu Yoshullilar

Our next stop is Hadiqotu Yoshullilar (the garden of leaders) where a late afternoon lunch is prepared. Visitors experience Khwarazmi cuisine in a traditional Uzbek setting, as well as a traditional Russian, Chinese and British settings. The Uzbeks are known for their hospitality. Shaykh Fodel explains that the city of Khwarazm has preserved the old infrastructure from the golden era more than any other city. We do not intend to visit this city during this tour. However, this is a city worth visiting as it was once a hub of Islamic knowledge and many scholars are attributed to it.

The Minor Congregational Mosque

We perform ʿAṣr Ṣalāh in the Minor (Manār/Minār) Congregational Mosque built by the former President, Islam Karimov. The Masjid can hold 7000 people at any one time. There is also a stream nearby, the timing of the day and the spring weather makes it perfect for a short stroll. Spring and Autumn are the best seasons to visit this region, although rain is predicted after a few days. Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī (d. 622/1225) mentions in Muʿjam al-Buldān (3:308) the greenery of the city, its flat nature (there are no mountains or hills), direct access to water in the homes and how the city is one of the cleanest in Transoxiana. This description is also true today.

Masjid Suzuk Ota

Our next stop is Masjid Suzuk Ota, which is another landmark of the city.

Masjid Shaykh Zayn al-Dīn

The final place we visit is Masjid Shaykh Zayn al-Dīn. Shaykh was a saint from Yemen, who is buried in the graveyard adjacent to the Masjid. The aforementioned Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq is also buried here. Many other scholars, Muftis and judges are buried here.

We perform Maghrib Ṣalāh here. Immediately after the Adhan, the post-Adhān supplication is read loudly, and Maghrib Ṣalāh commences immediately. After Ṣalāh, the Imam reads the Allāhumma anta al-Salām supplication loudly and people perform the Sunnah prayer. Thereafter, the Imam recites Subḥanallāh, Al-Ḥamdulillāḥ and Subḥānallah loudly once with pauses in between, prompting the congregation to read the masnūn adhkār. This is followed by the Imam reciting some Qurʾān and a short congregational supplication thereafter.

My respected father earlier recommended to the scholars at Dar al-Hilal that along with recitation of the Qurʾān, Imams should provide some translation and explanation, enabling the congregation to benefit from Islamic knowledge on a daily basis.

What is really promising is that the Masjid is full and the area surrounding the Masjid is very vibrant. The women’s section, however, is empty. In the month of Ramaḍān, the courtyard also fills up and there is a spill over outside the Masjid. This clearly demonstrates the revival of Islam in this region and the attachment of the people to Islam despite decades of communism. This change is welcome and will, if Allah wills, form the basis of the revival of the golden era.

It has been a long twenty-four hours. It is time to rest for the night.

Yusuf Shabbir

Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Day 2 – Sunday 14 April 2019

Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani arrives in Bukhara

High Speed Rail to Bukhara

It is an early morning start at 6.30am as we leave for one of Tashkent’s Rail Stations to travel on the 7.30am High-Speed train to Bukhara where our respected Shaykh al-Islam Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani is arriving later in the day. The distance between Tashkent and Bukhara is 580km, the journey by car takes seven to eight hours. However, the journey by the High-Speed train takes three hours and fifty minutes passing the city of Samarqand on the way.

The service is excellent; however, it is not a scenic route. The one-way fare is approximately 21 USD. The Uzbek currency is 8450 Som to one USD.

The service is excellent; however, it is not a scenic route. The one-way fare is approximately 21 USD. The Uzbek currency is 8450 Som to one USD.

Some jurisprudential issues

Accompanying us on this journey from Tashkent is Shaykh Fodel, Shaykh Rahmatullah, Shaykh Hikmatullah (a student of Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani), Shaykh Hasan (lecturer in Maʿhad al-Imam al-Bukhārī) along with Mufti Abdul Mannan. Mufti Abdul Mannan, a native Uzbek, speaks Urdu at an intermediate level, as he studied in Deoband in 2004 for his final year and has acquired Iftāʾ training in Deoband over the past decade by visiting for a few months periodically. We met him yesterday at Dar al-Hilal where he works and had an interesting discussion. He manages a local Fatwa website. Learning points include the complexity of Ṣalāh times (the UK is not alone!) which currently accord with 15 degrees or even less. Unlike the UK and Bulgar/Kazan, the Astronomical Twilight (18 degrees) disappears throughout the year. ʿAṣr Ṣalāh time begins at mithlayn, this again explains the practice in the Indian sub-continent unlike the practice of ḥanafīs in Shām and neighbouring regions. Twenty Rakʿat Tarāwiḥ Ṣalāh is the norm with complete recitation of the Qurʾān, eight does not exist and there is unity in this regard al-Ḥamdulillāh. Horse meat is prevalent. My respected father comments that the former Grand Mufti of India, Mufti Maḥmūd Ḥasan Gangohī (d. 1417/1996) permitted its consumption because horses are no longer used in warfare (Later our respected Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani confirms he has consumed horse meat). The government appointed Mufti’s position in relation to three divorces uttered together is that it is one.

Shaykh Raḥmatullāh asked my father regarding some prisoners who were jailed previously and restricted from performing any Ṣalāh. Some would perform via ishārah (gesture) whilst others would perform whilst walking. Is their Ṣalāh valid? My father replied: it is undoubtedly valid. It is worth noting that although the current situation is much better than before, certain restrictions remain. Preaching is restricted. All religious institutes are managed by the state. Private seminaries or supplementary classes (makātib) or durūs (lessons) cannot be established independently. It is for this reason, my respected father comments that wearing a scarf in these countries is also a great sacrifice and that one must avoid judging people.

Arrival into Bukhara

We arrive at Bukhara Rail Station at 11.20am, the recently built station is situated in the outskirts of the city. Bukhara is an ancient city which contains hundreds of well-preserved mosques, madrassas, bazaars and caravanserais, dating largely from the 9th to the 17th centuries. It was a prominent stop on the Silk Road trade route between the East and the West and a major medieval centre for Islamic theology and culture.

Its current population exceeds quarter million. Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī (d. 622/1225) mentions in Muʿjam al-Buldān (1:353) that he was unable to ascertain the origins and rationale of the name Bukhara. He further explains the story of its conquest in the era of the companion Muʿāwiyah (d. 60/680, may Allah be pleased with him).

Some local brothers receive us at the Train Station and take us to the As-Salam hotel in the centre of the historic city. Having used and listened to the term ‘Bukhārī’ thousands of times, one is full of emotion when entering the city and thinking about the life and era of Imam Bukhārī (d. 256/870) who was born here, acquired his early education here and also spent time here during his later life including before his demise.

Tour and history of Bukhara

After Ẓuhr Ṣalāh, we begin to tour the historic centre of Bukhara along with two friends from the UK who arrived here earlier in the day, Mufti Muhammad ibn Adam and brother Yahya Batha of Turath Publishers. The city is very clean similar to Tashkent. Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī (d. 622/1225) mentions in Muʿjam al-Buldān (1:353) that the city is very old, clean, with many gardens and wide range of fruits. Something unique I observe throughout this visit is that each ablution facility has two small towels for each person, a red towel to wipe the feet and another towel to wipe the other body parts.

People are very welcoming and given the way we dress are very eager to have themselves photographed with us. Irrespective of one’s position on photography and images, one must handle such situations with wisdom taking into account the current state of Islam in these countries and the challenges they face and the need to bring people closer to Islam.

The centre of Bukhara contains a number of mosques and madrasas which are all designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Encyclopaedia Britannica provides a useful summary of the history of this city, which is useful to quote to understand and appreciate the different influences on the city. It states:

“Bukhara, Uzbek Bukhoro or Buxoro, also spelled Buchara or Bokhara, city, south-central Uzbekistan, located about 140 miles (225 km) west of Samarkand. The city lies on the Shakhrud Canal in the delta of the Zeravshan River, at the centre of Bukhara oasis. Founded not later than the 1st century CE (and possibly as early as the 3rd or 4th century BCE), Bukhara was already a major trade and crafts centre along the famous Silk Road when it was captured by Arab forces in 709. It was the capital of the Sāmānid dynasty in the 9th and 10th centuries. Later it was seized by the Qarakhanids and Karakitais before falling to Genghis Khan in 1220 and to Timur (Tamerlane) in 1370. In 1506 Bukhara was conquered by the Uzbek Shaybānids, who from the mid-16th century made it the capital of their state, which became known as the khanate of Bukhara. Bukhara attained its greatest importance in the late 16th century, when the Shaybānids’ possessions included most of Central Asia as well as northern Persia and Afghanistan. The emir Moḥammed Raḥīm freed himself from Persian vassalage in the mid-18th century and founded the Mangit dynasty. In 1868 the khanate was made a Russian protectorate, and in 1920 the emir was overthrown by Red Army troops. Bukhara remained the capital of the Bukharan People’s Soviet Republic, which replaced the khanate, until the republic was absorbed into the Uzbek S.S.R. in 1924. It remained the capital when Uzbekistan gained independence in 1991. The city grew rapidly after the discovery in the late 1950s of natural gas nearby. The historic centre of Bukhara, designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1993, still retains much of its former aspect, with its mosques, madrasas (Muslim theological schools), flat-roofed houses of sun-dried bricks, and remains of covered bazaars. Among important buildings are the Ismāʿīl Sāmānī Mausoleum (9th–10th century); the Kalyan minaret (1127) and mosque (early 14th century); the Ulūgh Beg (1417), Kukeldash (16th century), Abd al-ʿAziz Khān (1652), and Mir-e-ʿArab (1536) madrasas; and the Ark, the city fortress, which is the oldest structure in Bukhara.”

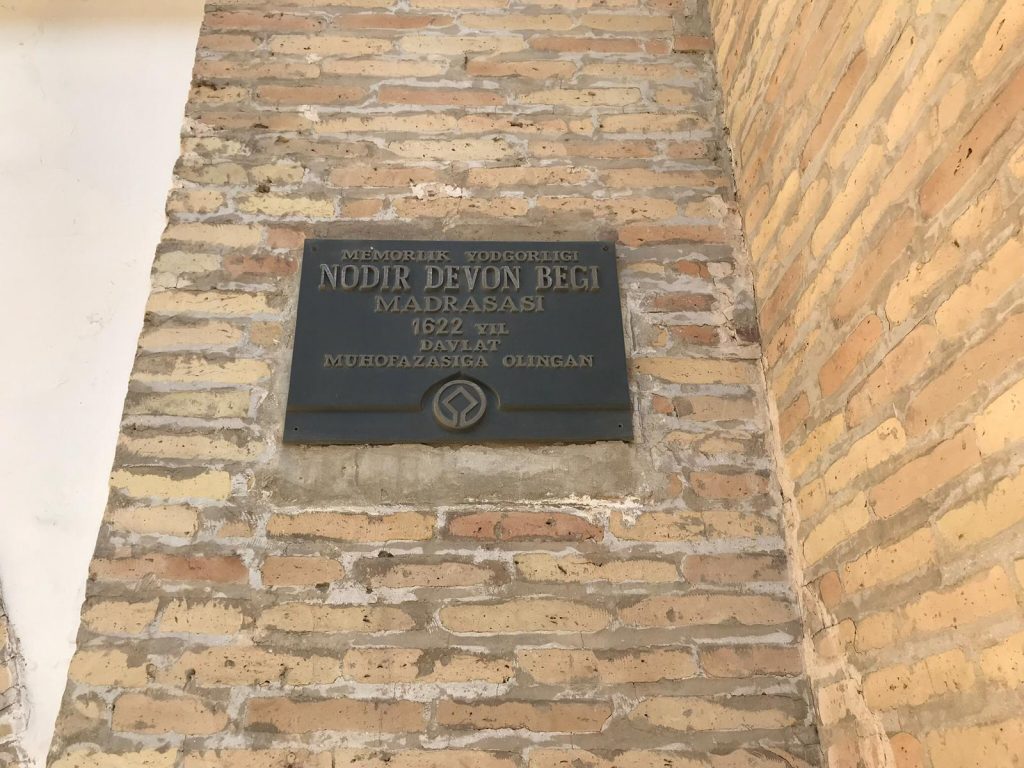

We visit the Nodir Devon Begi Madrasah as well as the Kokaldo Madrasah and observe the student dormitories and their living conditions.

Once upon a time, the city was a hub for Islamic learning. Students from all over the region would flock here to acquire Islamic education. Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī (d. 622/1225) mentions in Muʿjam al-Buldān (1:353) that the city is one of the greatest cities of Transoxiana and the most revered. Today, it is sad that most of these places only serve as tourist attractions. Bukhara is a popular tourist destination. As we head back to our hotel, we meet with a group from the UK led by Mufti Ashfaq of Bradford and also another group from South Africa led by Shaykh Ebrahim Bham. My respected father Mufti Shabbir Ahmed comments that it was only the grace of Allah Almighty upon Imam Bukhārī, the non-Arab, from a city located beyond River Oxus far from Arabia, adding that it is remarkable how thousands of students would flock here to acquire Islamic education and ḥadīths despite the difficulties in travelling.

Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani arrives from Moscow

Later in the afternoon at 5.30pm, Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani lands at Bukhara International Airport from Moscow with his wife, his son Dr Mawlana Imran Ashraf Usmani and grandson Mohammed Abdullah Usmani, who is currently training to become a scholar. Mufti Ṣāḥib was invited to Russia by the National Research University Higher School of Economics, a prestigious institution similar to the London School of Economics, to deliver speeches on Islamic Finance to a select group of top academics and senior executives. Mufti Ṣāḥib later informs us that they were all non-Muslims who listened very attentively and visited him personally in Karachi to extend an invitation. Mufti Ṣāḥib visited Russia once prior to this 12-14 years ago and noted a material difference in the situation of Muslims. In Moscow alone, there are 2 million Muslims and the main Mosque can hold 15,000 worshippers, making it the largest mosque in Europe. Mufti Ṣāḥib delivered the Friday sermon here and there were 20,000 people present with a spill over outside.

We greet Mufti Ṣāḥib at the hotel after Maghrib Ṣalāh and are delighted to see that he is in good health, al-ḥamdulillah. He shares with us some details of the failed assassination attempt on him. The hosts have arranged a tour of the old city. We walk whilst Mufti Ṣāḥib is driven in an electric rickshaw. The guide explains that there are some Jews that reside here and there is also a synagogue. A cursory search online indicates that there are only a few Jewish families remaining here, however, there are 10,000 graves of Jews here, which suggests that Bukharan Jews lived here in large numbers. Many have migrated to Palestine following the catastrophe (nakhbah) in 1948.

As we tour the historic centre, we pass the water canal which would supply water to the residents of the city in the past. The guide highlights a Mulberry Tree which dates back to 1477 CE.

Mufti Ṣāḥib explains that he visited Bukhara and this country in 1992 and notes a big difference. The purpose of his visit then with a group of other scholars was to highlight the Qadiyani/Ahmedi problem. He was unable to write about this trip due to commitments. We go through the Taqi-Sarrafon (Dome of moneychangers) market, one of the city’s domed bazaars of medieval times. This is where traders from India, China and other places would visit and exchange money.

The Magok-i-Attari Mosque

Next, we pass the Magok-i-Attari Mosque which is another historical mosque here with octagonal domes. It was built around the 10th century on the remains of a Zoroastrian temple from the pre-Islamic era. It is one of the oldest surviving mosques in Central Asia and one of the few surviving buildings in Bukhara from the time before the Mongolian invasion. Unfortunately, today, the mosque is used as a carpet museum. We also visited this earlier in the day.

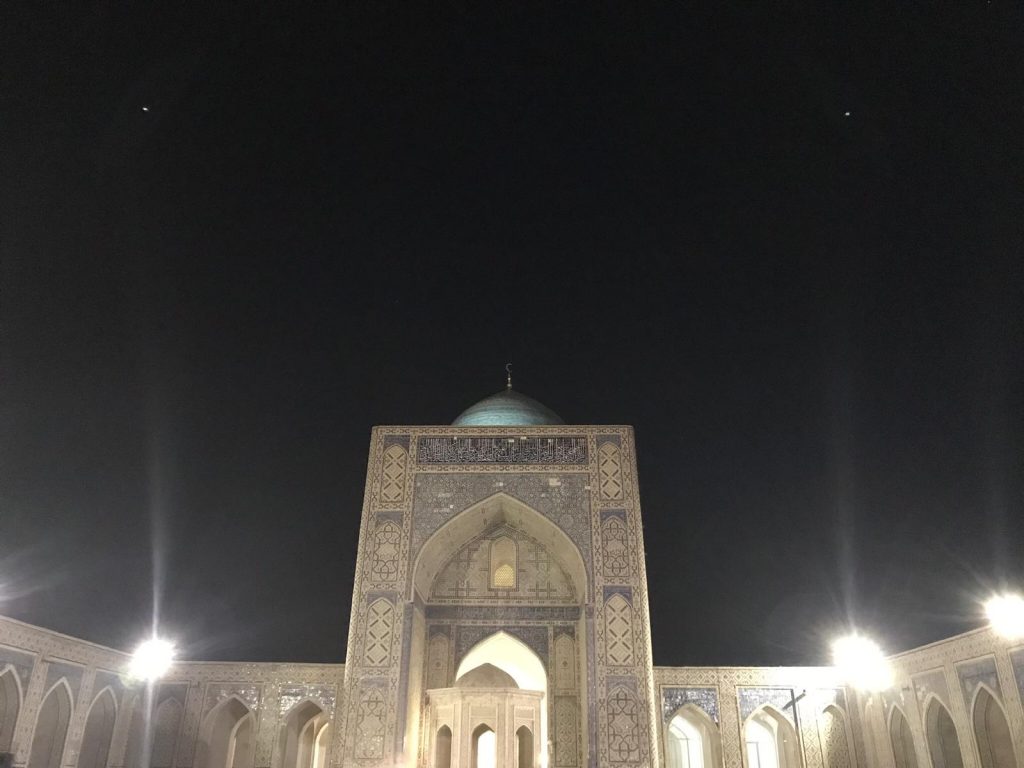

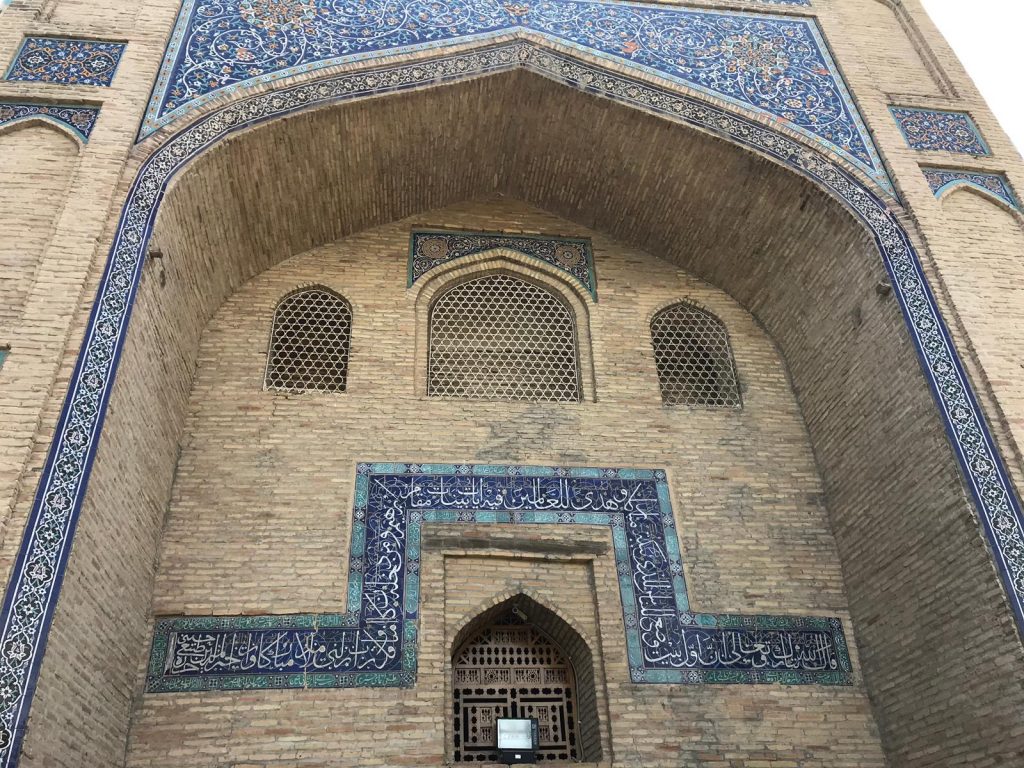

The Kalan Mosque, Minaret and Mir-i-Arab Madrasah

We head towards the famous Kalan Mosque which is one of the outstanding monuments of Bukhara, dating back to the fifteenth century during the era of the Sheybanids. The roof of the galleries encircling the mosque’s inner courtyard has 288 domes resting on 208 pillars. Facing the courtyard is a tall tiled Iwan portal, for entry to the main prayer hall. The mosque is surmounted by a large blue tiled dome. This is the mosque where Imam Bukhārī (d. 256/870) is reported to have taught ḥadīth, some 20,000 students would participate in his lessons. However, the current structure did not exist at the time. The current structure was preceded by the Karakhanid Djuma Mosque, which was made of wooden structure and subsequently destroyed by fire during the Mongolian invasion.

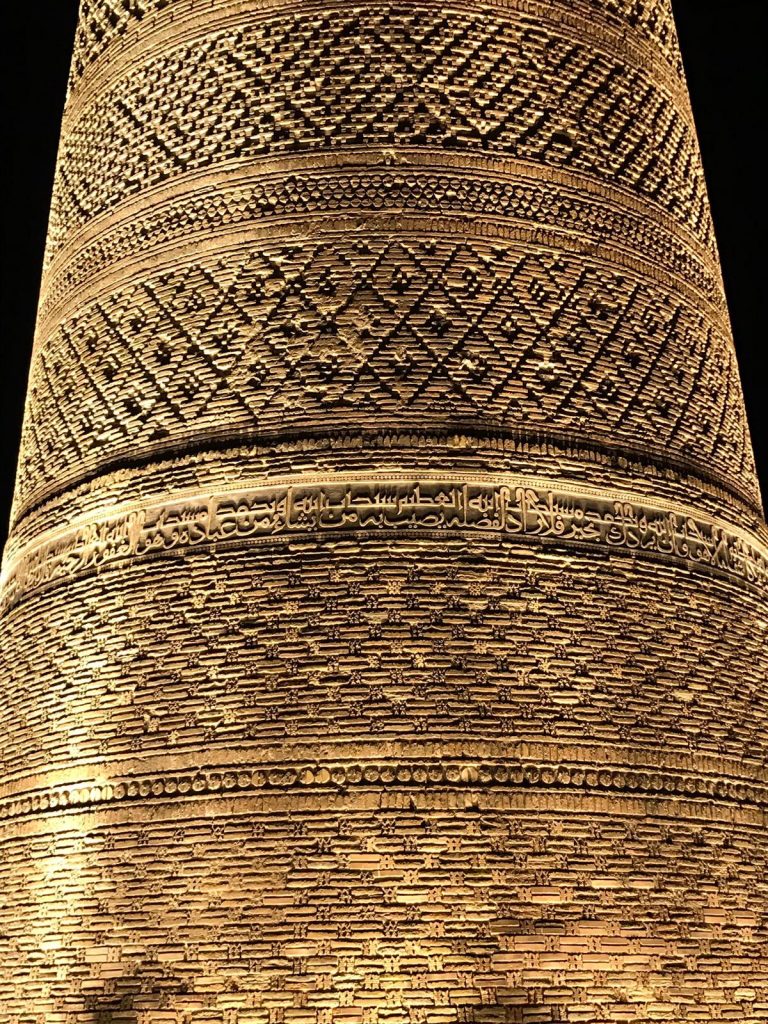

As we approach the Masjid, the beautiful Kalan minaret comes into clear view. It is also known as the Tower of Death because for centuries criminals were executed by being thrown from the top. The minaret, designed by Bako, was built by the Qarakhanid ruler Mohammad Arslan Khan in 1127 CE for the adhān. It is made in the form of a circular-pillar brick tower, narrowing upwards, of 9 meters diameter at the bottom, 6 meters overhead and 45.6 meters high.

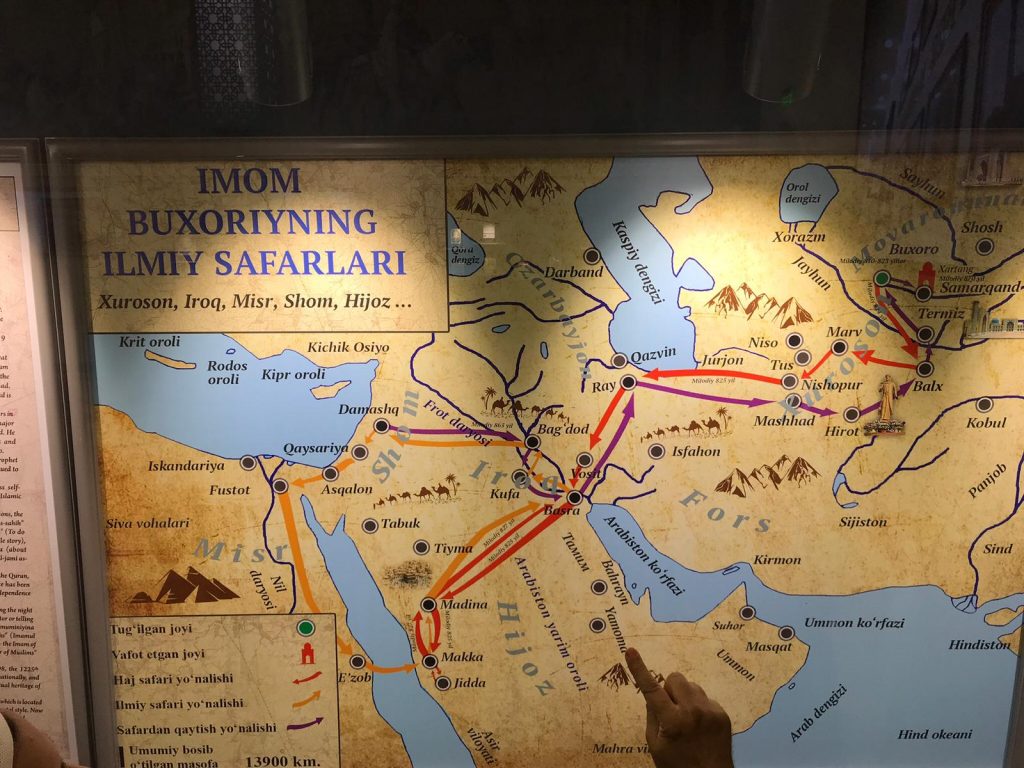

As we enter the Masjid, Mufti Ṣāḥib comments, “I can feel and sense the fragrance of knowledge in the air”. He adds, “I am thinking about the era of Imam Bukhārī, I am picturing the scenes of this centre of knowledge.” Mufti Ṣāḥib adds that Imam Bukhārī travelled approximately 14,000km in the pursuit of knowledge on foot and on animals. Allah Almighty created him to protect and preserve the Sunnah, it appears that he was created for this purpose. He was not an Arab, yet, all Arabs and non-Arabs depend on his works and attest to his credentials. We perform ʿIshāʾ Ṣalāh here in the Masjid.

In the courtyard within the Masjid complex, there is a platform where Genghis Khan’s army killed 14,000 scholars, and during the more recent soviet rule, many hundreds of scholars and Imams were killed. The guide mentions that there was perhaps a well here, where all the bodies were thrown into and the platform was built on top of it in memory of those killed. During the Mongolian invasion, copies of the Qurʾān were scattered all over the mosque yard, and the chests where these copies were stored were utilised to feed the Mongols’ horses.

Opposite the Masjid is the famous Mir-i-Arab (prince of Arabia) Madrasah, the only madrasah in the entire Soviet Union that operated during Soviet rule. It was established in 1535 by the Yemeni scholar, Shaykh ʿAbdullāh Yemeni, who is also buried here. He was a disciple of Shaykh ʿUbaydullāh Aḥrār (d. 895/1490) who is buried in Samarqand. When the Safavids attacked Bukhara, Shaykh ʿAbdullāh Yemeni played a leading role in repelling them. In return, the ruler gave money to Shaykh to build the Madrasah. However, he passed away before construction completed. Once complete, the Madrasah operated from its inception until it was closed in 1920, and was subsequently reopened by Stalin in 1944 in an effort to gain Muslim favour for his war effort. Tomorrow, we are scheduled to visit this Madrasah.

During the late evening meal, Mufti Ṣāḥib reflects on the work of Dar al-Hilal and mentions that he knew Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq very well. He was very balanced, learned and wrote many books. He also served as a Parliamentarian and served on many international Islamic organisations. My respected father mentions that the ḥadīth pertaining to mujaddids is general and not restricted to one person in an era and that Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq was a mujaddid of this region. Mufti Ṣāḥib concurs.

In other developments, Mufti Ṣāḥib shares that the 8th, 9th and 10th volumes of his Inʿām al-Bārī (the Urdu lessons of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī) have been published. A discussion follows regarding his visit to Iran and how most of the landmarks related to Sunni scholars including of Imam Muslim (d. 261/875) in Nishapur have been destroyed. The excellent work of Jamiah Darul Uloom Zahedan is highlighted, where Mufti Ṣāḥib has students. Mufti Ṣāḥib has students all over the world. Only today, a group of scholars arrived here from Tajikistan, some of whom studied in Darul Uloom Karachi, to spend some time with Mufti Ṣāḥib.

Day 3 – Monday 15 April 2019

The saints and scholars of Bukhara

The morning tour of Bukhara begins with a visit to the tombs of two of the great saints of the Naqshbandī Sufi chain. There are four famous Sufi chains, Naqshbandī is the prevalent chain in this region and is named after its founder, Shaykh Bahāʾuddīn Naqshband (d. 791/1389). He is buried in Qasr-e-Aarifan, a short drive from Bukhara city.

Tomb of Shaykh ʿAbdul Khāliq Gijdiwānī (Gijduvon, Bukhara)

However, our first stop is to the tomb of another Naqshbandī saint Shaykh ʿAbdul Khāliq Gijdiwānī (d. 575/1179) who is number 11 in the Naqshbandī chain, as illustrated in the following list:

- Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ (d. 11/632).

- The companion Abū Bakr al-Ṣiddīq (d. 13/634, may Allah be pleased with him).

- The companion Salmān al-Fārisī (d. 33/654, may Allah be pleased with him).

- Imam Qāsim ibn Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr al-Ṣiddīq (d. 101 or 106 or 107).

- Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (d. 148/765).

- Shaykh Bāyazīd Bisṭāmī/Basṭāmī (d. 261/875).

- Shaykh Abū al-Ḥasan al-Kharaqānī (d. 425/1033).

- Shaykh Abū al-Qāsim al-Gurgānī (d. 450/1058).

- Shaykh Abū ʿAlī Farmādī (d. 477/1084 or 511/1117).

- Shaykh Abū Yaʿqūb Yūsuf Hamadānī (d. 535/1141).

- Shaykh ʿAbdul Khāliq Gijdiwānī (d. 575/1179).

- Shaykh ʿĀrif Reogārī (d. 616/1219).

- Shaykh Maḥmūd Anjīr-Fagnāwī (d. 717/1317).

- Shaykh ʿAzīzan ʿAlī Ramitānī (d. 715/1315 or 721/1321).

- Shaykh Muḥammad Bābā Samāsī (d. 755/1354).

- Shaykh Sayyid Amīr Kulāl (d. 772/1370).

- Shaykh Bahāʾuddīn Naqshband (d. 791/1389).

Mujaddid al-Alf al-Thānī, Shaykh Aḥmad Sarhindī (d. 1034/1624), who was based in India, is 25th in this chain. All the saints from Shaykh ʿAbdul Khāliq Gijdiwānī to Shaykh Bahāʾuddīn Naqshband lived and passed away in Uzbekistan. As Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani remarks, “this area is full of saints.” It appears, and Allah knows best, judging from the dates and the areas served by these saints that the Sufi chains was not prevalent in Bukhara in the era of Imam Bukhārī (d. 256/870), and Allah knows best. However, in subsequent centuries, the Naqshbandi chain became prominent in this region.

Shaykh ʿAbdul Khāliq Gijdiwānī’s grave is located in Gijduvon town, 47km from Bukhara city on the way to Samarqand. It is an hour drive. It is raining as we arrive and it has been raining since last night. The weather has changed drastically since yesterday. There is a very large memorial complex built at the site of the grave.

The Scientist and ruler Ulugh Beg (d. 853/1449) established a Madrasah next to the tomb, just as he established a madrasah in Bukhara city and also a third one in another location. Unfortunately, the madrasah here is not operational, however, a local scholar confirms that there are plans to re-start it. He adds that the country suffered from communism for seventy years, however, the situation is improving now. People love Isla and all our names are Islamic. He further adds that there are graves of scholars and saints all over the region and it is for this reason our scholars would recommend people to perform ablution before leaving the homes.

Tomb of Shaykh Bahāʾuddīn Naqshband and Madrasah Mir-i-Arab (Advanced)

We return towards Bukhara city and proceed towards the tomb of Shaykh Bahāʾuddīn Naqshband, located in the outskirts of the city. His full name is Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Bukhārī. He is the founder of the Naqshbandī Sufi order. His statements include: “Attachment with anyone besides Allah is a great barrier for the sālik (the one treading the path of sulūk).” He would also emphasise on following the Sunnah (Shaqāʾiq al-Dawlat al-ʿUthmāniyyah, p.154).

We arrive here at 11.45am. There is a large memorial complex built around his grave and we observe many visitors.

Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani recalls that on his previous visit in 1992, the grave was not solid. We all recite some Qurʾān at the grave. Mufti Ṣāḥib’s practice when visiting graves is to very quietly recite Surahs Fātiḥah, Ikhlāṣ, Mulk and also Sūrah Yāsīn subject to time.

Perhaps, the greatest source of inspiration and happiness for us is the branch of the Mir-i-Arab Madrasah here adjacent to the grave. The Mir-i-Arab Madrasah Mutawassiṭah (intermediate) is located opposite the Kalan Mosque in the centre of Bukhara, and the Mir-i-Arab Madrasah ʿĀliyah (advanced) is situated here. There are 100 students studying advanced Islamic studies here who have all gathered in the lecture hall. A student reads the chapter of the virtue of Shām from Sunan al-Tirmidhī and the ḥadīth therein with the full chain of Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani to Imam Tirmidhī (d. 279/892) and beyond. This is followed by an Arabic lecture delivered by Mufti Ṣāḥib which is well received.

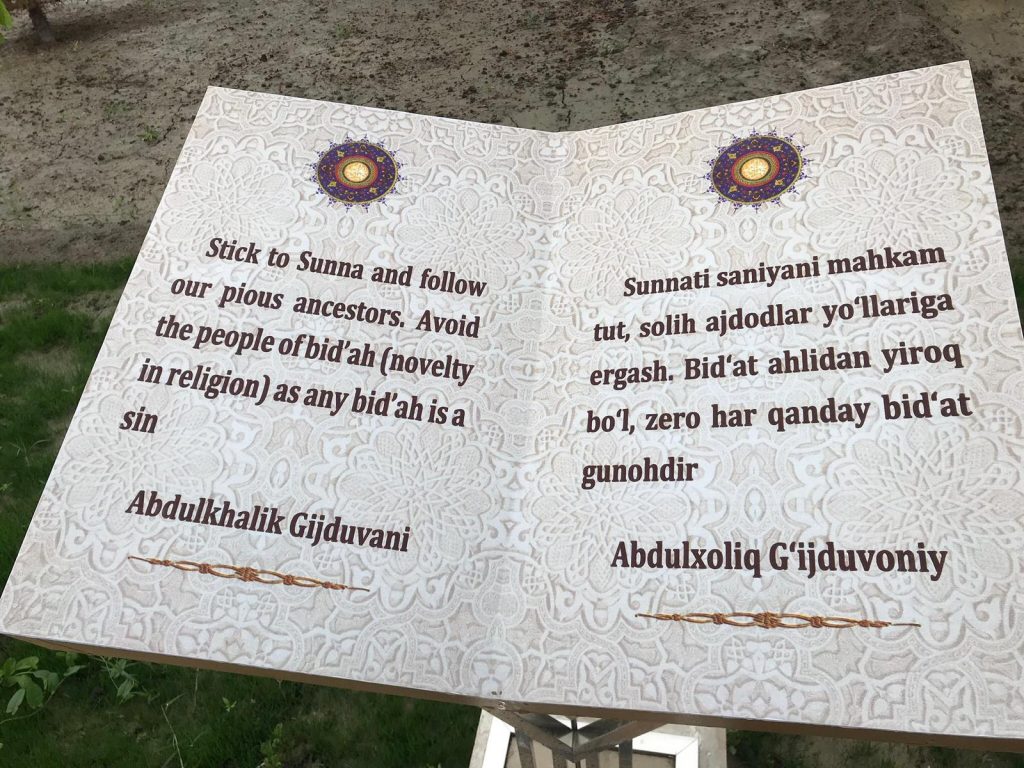

The summary of Mufti Ṣāḥib’s lecture is as follows, “Knowledge on its own does not benefit. My father Mufti Muḥammad Shafīʿ [d. 1396/1976] would say, ‘if knowledge was the criterion for a person’s virtue, then Satan was the most knowledgeable, however, his knowledge did not benefit him, because he disobeyed Allah.’ Therefore, knowledge alone is not in itself the primary objective. The primary objective is the obedience of Allah and his Messengers. Therefore, the purpose of studying books like Sunan al-Tirmidhī is to understand the ḥadīths pertaining to all aspects of life and act upon them. A person should follow the Sunnah in every aspect of the inner and the outer. Behind you is Shaykh Bahāʾuddīn who emphasised on following the Sunnah and abstaining from innovations. Mujaddid al-Alf al-Thānī, Shaykh Aḥmad Sarhindī has written in his makātīb that he acquired all the sciences of the outer and thereafter the inner until he reached its peak. After reaching this lofty status, he would remark, ‘I supplicate to Allah to enable me to live on the Sunnah and die upon the Sunnah.’ This is the purpose of these Sufi chains. The purpose is one which is to follow the Sunnah, although their routes may vary. We have just returned from the grave of Shaykh ʿAbdul Khāliq Gijdiwānī and a quote of his was written there [with its English translation as it appears there], ‘Stick to Sunna and follow our pious ancestors. Avoid the people of bid’ah (novelty in religion) as any bid’ah is a sin.’”

Mufti Ṣāḥib granted ijazah in ḥadīth to all attendees. The Principal and the teachers gifted a special Bukharan turban, a Jubbah and a pair of shoes to Mufti Ṣāḥib which he wore immediately. The picture has already circulated worldwide.

Tomb of Imam Abū Ḥafṣ al-Kabīr and Imam Abū Ḥafṣ al-Ṣagīr

Our next stop is the memorial complex in Bukhara city that houses the graves of four scholars:

- Imam Abū Ḥafṣ al-Kabīr (d. 217/832).

- His son Imam Abu Ḥafṣ al-Ṣagīr (d. 264/878).

- His grandson ʿAbdullāh ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Ḥafṣ (n.d.) and

- The muḥaddith and faqīh Abū Muḥammad ʿAbdullāh ibn Muḥammad ibn Yaʿqūb al-Ḥārithī al-Bukhārī al-Kalābādhī ( 340/952) who compiled the Musnad of Imam Abū Ḥanīfah (see Siyar 15/424 for his profile).

Imam Abū Ḥafṣ al-Kabīr whose name is Aḥmad ibn Ḥafṣ is a senior ḥanafī jurist who studied directly with Imam Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Shaybānī (d. 189/805) along with other great scholars such as Imam Wakīʿ ibn al-Jarrāḥ (d. 197/812). He was born in the year 150 Hijrī, the year in which Imam Abū Ḥanīfah (d. 150/767) passed away. He is also a teacher of Imam Bukhārī. Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī (d. 748/1348) describes him in Siyar (10:157) as “the faqīh, the ʿAllāmah, Shaykh of Transoxiana, the jurist of the east” and mentions Bukhara as his place of death. Along with his knowledge, he was known for his piety and good deeds. His quote pertaining to gifting gifts during the religious festivals of non-Muslims is also cited widely in non-ḥanafī fiqh and ḥadīth commentary books. He is also the transmitter of Kitāb al-Ḥiyal from Imam Muḥammad, as mentioned by ʿAllāmah Sarakhsī (d.ca. 490/1097) in al-Mabsūṭ (30:209). When I mention this to Mufti Ṣāḥib, he mentions that I do not know whether the published work that has reached us is indeed this or otherwise. He adds that during his 1992 visit to Bukhara, there was no memorial complex at this site. We understand it was built ten years ago.

Imam Abū Ḥafṣ al-Kabīr’s son is Imam Abū ʿAbdillāh Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Ḥafṣ, also known as Abū Ḥāfṣ al-Ṣagīr. He is also a very senior ḥanafī jurist. Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī describes him in Siyar (12:617) as “the scholar of Transoxiana, Shaykh al-Ḥanafiyyah” adding that he was an Imam, trustworthy, God-fearing, pious, abstinent and an adherent of the Sunnah. He is Imam Bukhārī’s contemporary and accompanied him for a period in the pursuit of knowledge. Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī mentions that he was involved in the expulsion of Imam Bukhārī before his demise, however, ʿAllāmah Kashmīrī (d. 1352/1933) has expressed doubt regarding his involvement in Fayḍ al-Bārī (2:351) because of their relationship in their early life and the affection between the two. It is possible that his position may have changed or he was misinformed. Nevertheless, scholars before Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī do not appear to mention Abū Ḥafṣ al-Ṣagīr’s involvement which adds to the doubt.

A more important point is to be noted here. Many of our ḥanafī jurists have mentioned that Imam Bukhārī gave a Fatwā when he was young despite Imam Abū Ḥafṣ al-Kabīr stopping him that if two babies are fed milk of the same animal, this will establish Ḥurmat Raḍāʿah (foster relationship). Thereafter, the people evicted him from Bukhara. A few months ago, I was asked regarding this and I wrote a detailed answer online. The first jurist to mention this appears to be ʿAllāmah Sarakhsī (d.ca. 490/1097), and later jurists appear to have transmitted this from him. We have not come across any evidence that Imam Bukhārī returned to Bukhara before the demise of Imam Abū Ḥafṣ al-Bukhārī and started issuing edicts. It appears to be an error in transmission. Imam Ibn al-Mundhir (d. 318/930-1) has cited the Ijmāʿ (consensus) of scholars that drinking milk from the same animal does not establish ḥurmat (prohibition). Mawlānā ʿAbd al-Ḥayy Laknawī (d. 1304/1886) has also expressed doubts about this story and our respected teacher Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Muḥammad Yūnus Jownpūrī (d. 1438/2017) was firmly of the view it is unsubstantiated.

It is also worth noting that according to some scholars, Imam Bukhārī was forced to leave Bukhara on up to four occasions. However, this appears to be unsubstantiated, as we have only come across evidence for him being forced to leave once shortly before his demise following his refusal to give private tuition to the sons of Emir Khālid ibn Aḥmad al-Dhahalī (d. 270/883), who had also received a letter from Muḥammad ibn Yaḥya al-Dhahalī (d. 258/872) of Nishapur, complaining about Imam Bukhārī.

Returning to our tour, we perform Ẓuhr Ṣalāh in the Masjid near these graves. The Masjid for some reason has a semi-circular dome.

Grave of Shams al-Aʾimmah al-Ḥalwānī

Following the afternoon Siesta and performing ʿAṣr Ṣalāh, we visit the grave of Shams al-Aʾimmah al-Ḥalwānī (d. 452/1060), a senior ḥanafī jurist and teacher of Shams al-Aʾimmah al-Sarakhsī. Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī describes him in Siyar (19:415) as “Imam, ʿAllāmah, Mufti of Bukhara” and mentions his strong memory as well as the title “Abū Ḥanīfah al-Aṣgar” used to describe him. His grave is located within the old city in the Samarqand area. We enter from the Samarqand gate to reach this place. Bukhara in the past had twelve doors, the Samarqand gate is one of them. Many people mispronounce his name as Ḥulwānī. Whilst Ḥulwān is a name of a place in the Diyala province of eastern Iraq, with Imam Ḥasan ibn Alī al-Khallāl (d. 242/857) attributed to it, the correct attribution here is Ḥalwānī, from Ḥalwā (sweets), perhaps because Shams al-Aʾimmah al-Ḥalwāni’s family or ancestors were traders of sweets (see al-Ansāb, 4:213, 216; al-Jawāhir al-Muḍiyyah, 1:318, 2:561; al-Fawāʾid al-Bahiyyah, p.96).

Mufti Muhammad Taqi Ṣāḥib mentions that ʿAllāmah Sarakhsī’s grave is in Uzjund, Fergana, Kyrgyzstan, adding that some of Fergana is also in Uzbekistan. Imam Qāḍīkhān (d. 592/1196) is also buried in Ozjund. Both need little introduction. ʿAllāmah Sarakhsī was imprisoned in a jail, from where he authored his thirty volume al-Mabsūṭ, the commentary of al-Kāfī, along with parts of the commentary of al-Siyar al-Kabīr. Both commentaries are published. Another scholar to have authored a notable work in prison is Shaykh al-Islam Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 728/1328), who authored the masterpiece al-Ṣārim al-Maslūl in prison.

Visiting graves

At this juncture, it is worth briefly touching upon the ruling pertaining to travelling long distances for the purpose of visiting graves. Scholars and jurists have differing approaches to this, as outlined in my book, Kitab al-Arbaʿīn fī Ḥubb al-Nabī al-Amīn ﷺ. The balanced approach is that travelling long distances solely for the purpose of visiting a grave is not Sunnah nor desirable, however, if a person travels to a place for the purpose of propagating dīn, or assisting the people, or to acquire or impart knowledge, there is no harm in supplementing this with visits to local graveyards, and if there are graves of local scholars and saints such as those mentioned above, this is commendable. This should, however, not be the sole intention.

Imam Bukhārī’s birth place

Next, we visit Masjid Hoja Zaynuddin in the old city and perform Maghrib Ṣalāh here. Outside the Masjid is a large deep pi where it is suggested that Imam Bukhārī was born, Allah alone knows best. A local guide mentions that the Masjid was built a few hundred years ago from the soil of the birth place of Imam Bukhārī, which was then converted into a pit to avoid the place being desecrated. I am fortunate to read a ḥadīth here to Mufti Ṣāḥib. The guide adds that during communism, twenty scholars were killed here by the Soviets.

Mir-i-Arab Madrasah

Our final stop for the day is the Mir-i-Arab Madrasah Mutawassitah (intermediate) opposite the Kalan Mosque. We saw the Madrasah from outside yesterday. Today is our opportunity to visit the Madrasah. After visiting the tomb of Shaykh ʿAbdullāh Yemeni, Mufti Ṣāḥib delivers a speech in Arabic for the students.

He begins by recording his gratitude and explains the fragrance and nūr (light) that has spread from here across the world. He proceeds to read the ḥadīth al-raḥmah and grants ijāzah in ḥadīth. This is followed with a brief explanation focusing on the importance of mercy on Muslims and non-Muslims highlighting that this is the first ḥadīth taught to a student of ḥadīth. Regarding non-Muslims, our mercy towards them is to have a burning rage and desire within the heart for them to be saved from the eternal punishment.

The speech is followed by Q&A. In response to a question regarding Imam Tirmidhī’s use of the phrase “And some Kufans said”, Mufti Ṣāḥib explained that it is not a specific reference to Imam Abū Ḥanīfah (d. 150/767), rather it refers to a group of Kufan scholars. My respected father adds that this is not jarḥ (narrator criticism) and quotes Shaykh Muḥammad Zakariyyā Kāndhelwī (d. 1402/1982) who adds that in some versions of Sunan al-Tirmidhī, Imam Abū Ḥanīfah’s famous criticism of the controversial ḥadīth narrator Jābir al-Juʿfī (d. 127/744-5) is mentioned. This demonstrates that Imam Tirmidhī accepted Imam Abū Ḥanīfah’s authority on character discernment. A student asks regarding the lack of experiencing ḥalāwat (sweetness) when reciting the Qurʾān. Mufti Ṣāḥib advises to continue with the recitation, as experiencing sweetness is in itself not an objective, the objective is to please Allah Almighty. If sweetness is experienced then it is welcome, otherwise, it should not deter a person from continuing to recite.

Finally, Mufti Ṣāḥib addresses the question of tabarruk (taking blessings from the pious) explaining that there are two extremes in this regard. Some people reject it altogether and suggest it is shirk. This is wrong because there are several ḥadīths that affirm tabarruk. On the other hand, some people have total reliance on tabarruk and do not perform good deeds. Citing the example of the hypocrite ʿAbdullāh ibn Ubayy ibn Salūl (d. 9/631), he emphasises that tabarruk is of no benefit to he who performs no good deeds.

The students and staff at the Madrasah are very friendly, cordial and helpful. They ask questions and are very interested in the Islamic sciences. This is a great bounty of Allah when considering the seventy-year era of communism.

During the day, several other jurisprudential issues are discussed with Mufti Ṣāḥib. A local person enquired regarding an extreme case of a woman who is required to travel to Egypt to meet up with her husband, the husband is unable to afford to travel to Bukhara to collect her, can she travel? Mufti Ṣāḥib answers in short, “she can travel and she must seek forgiveness” adding that she should be dropped to the Airport by a maḥram and collected at the destination by her husband. The prevalent practice of Adhkār, double collective supplication and the recitation of the Qurʾān after each Ṣalāh in this region is also discussed. Mufti Ṣāḥib explains that people have started to regard it as part of the Ṣalāh and this iltizām (considering it necessary or implying that) is problematic. In addition, this could deter a person from attending congregational Ṣalāh altogether. When invited to travel for a completion of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī programme, Mufti Ṣāḥib does not travel for this purpose due to the emerging iltizām. At one point, Mufti Ṣāḥib mentions the short life of Mawlānā ʿAbd al-Ḥayy al-Laknawī (d. 1304/1886) and how he was a Mujtahid fī al-Madhhab.

We also learn during the day that many residents of Bukhara can converse in Persian. Imam Bukhārī has also used certain Persian words in his Ṣaḥīḥ.

Grave of ʿAbdullāh ibn Muḥammad al-Musnadī

Imam ʿAbdullāh ibn Muḥammad al-Musnadī (d. 229/) is a teacher of Imam Bukhārī. Many of his ḥadīths are transmitted in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. He is known as Musnadī because of his focus on musnad ḥadīth. This attribution ‘musnadī’ appears with his name in at least one place in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī (25). His grandfather is Yamān, on whose hands Imam Bukhārī’s grandfather Ibrāhīm accepted Islam. He passed away in Bukhara (Siyar, 10:658). We are unable to visit his grave as it closed at 6pm, however, this is worth noting.

It is now time to rest as in less than four hours we have to depart from Bukhara.

Yusuf Shabbir

Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Day 4 – Tuesday 16 April 2019

From Bukhara to Samarqand

It is a very early morning start at 4am as we head to Bukhara Rail Station to travel on the 4.55am High Speed Rail to Samarqand.

Joining us on this trip today is Mufti Abdurrahman Mangera from London and Dr Mawlana Asmar Akram from Scotland who arrived yesterday following a 48-hour journey. Leaving from Bukhara for Samarqand reminds a person about the final journey of Imam Bukhārī when he was forced to leave his home town. Imam Bukhārī headed towards Samarqand and arrived at a village 30km from Samarqand, known as Khartank, where he had some relatives. It was here, he made his famous supplication, “O Allah, the earth has become narrow upon me, so take away my soul.” He passed away shortly thereafter and was buried in the same village. Fragrance emitted from his grave for many days and his detractors realised their error and repented (refer to Siyar, 12:443, for further details).

Welcome at Samarkand Rail Station

We arrive Samarkand at 6.30am and are warmly received by Imam Zaynuddin, the Imam of Masjid Bukhari as well as the Qāḍī of Samarqand. The jurisdiction of a Qāḍī is primarily confined to family law in this country. Born in 1967, Imam Zaynuddin grew up during communism and it was during this period he memorised the Qurʾān privately in remote mountains and deserted areas, generally during the dark hours of the night. One Qurʾān would be shared between five students. Mufti Muhammad Taqi Ṣāḥib compliments him by saying: انتم ذقتم حلاوة الإيمان (you people have tasted the sweetness of faith), adding that we have not tasted it in the same way because we have inherited Islam from our forefathers without any sacrifice.

Samarkand

Samarkand has been described the paradise of this world (Muʿjam al-Buldān, 3:246) and is known for its mosques and mausoleums. It is situated on the Silk Road, the ancient trade route linking China to the Mediterranean. Prominent landmarks include the Registan, a plaza bordered by 3 ornate, majolica-covered madrassas dating to the 15th and 17th centuries, and Gur-e-Amir, the towering tomb of Timur, founder of the Timurid Empire. Its population exceeds half a million. It was once the hub of knowledge and many thousands of scholars lived here. Today, the city is well established in terms of its infrastructure.

Imam Bukhārī’s grave, Khartank

Out first stop without any rest is the grave of Imam Bukhārī who requires no introduction. In the words of our teacher Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Muḥammad Yūnus Jownpūrī (d. 1438/2017) who taught Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī continuously for 50 years and visited Imam Bukhārī’s in the early 90s, Imam Bukhārī was a miracle of the Prophet ﷺ, which manifested more than 200 years after his demise. He passed away in Khartank, which is 30km from Samarqand city, as mentioned above. There is a large memorial complex at the site that was built in recent years. There are many people here. The one positive point we note here and elsewhere is that there are no apparent polytheistic practices taking place, unlike some other parts of the world.

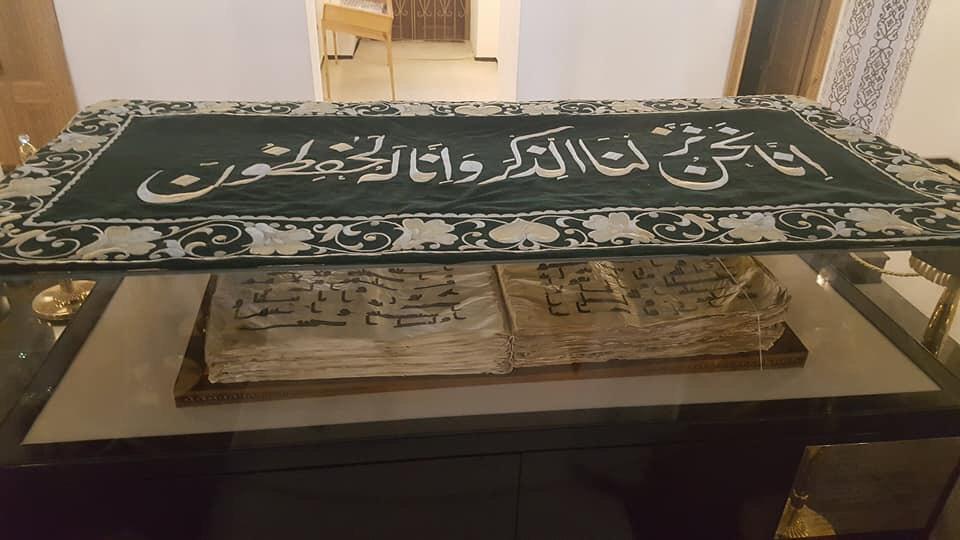

A staircase leads down to a room were the grave lies draped in a green cloth.

Words cannot describe the inner feeling as we enter the room. After reciting some Qurʾān quietly, Mufti Muhammad Taqi Sahib reads the first ḥadīth of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī in a very emotional tone with tears in his eyes. I have not seen him in such an emotional state. Mufti Ṣāḥib instructs me to read the final ḥadīth of the Ṣaḥīḥ. Mufti Ṣāḥib, my respected father and all those present turn to the Qiblah and start to supplicate quietly. Tears flow from the eyes, for we are all indebted to him forever.

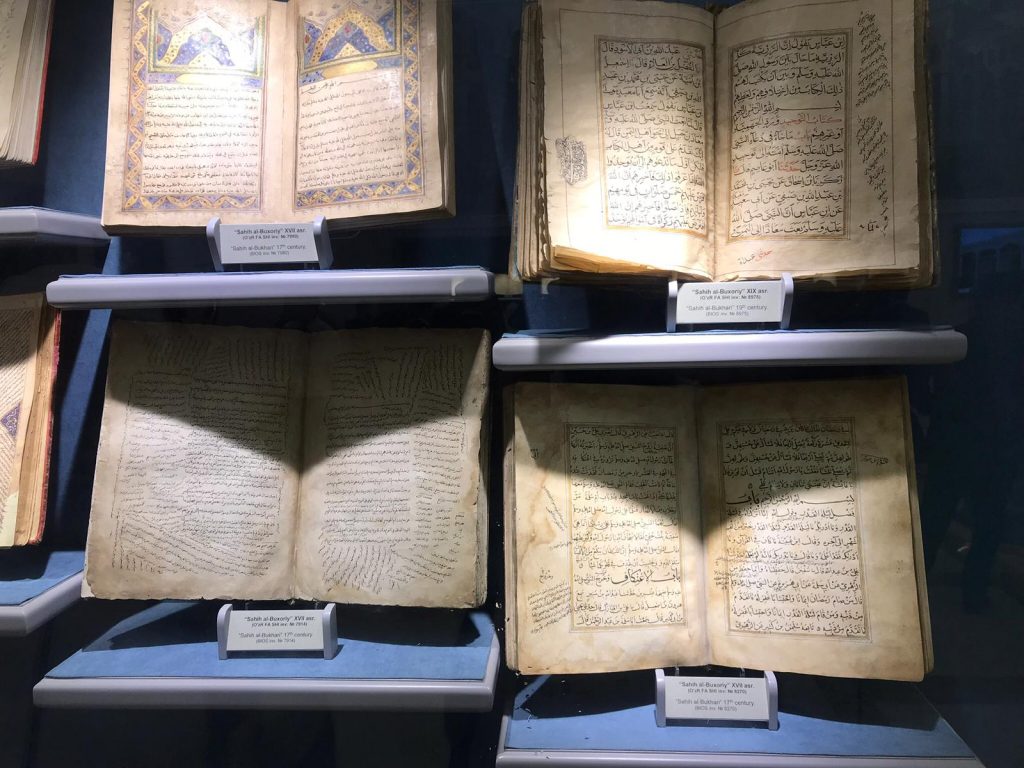

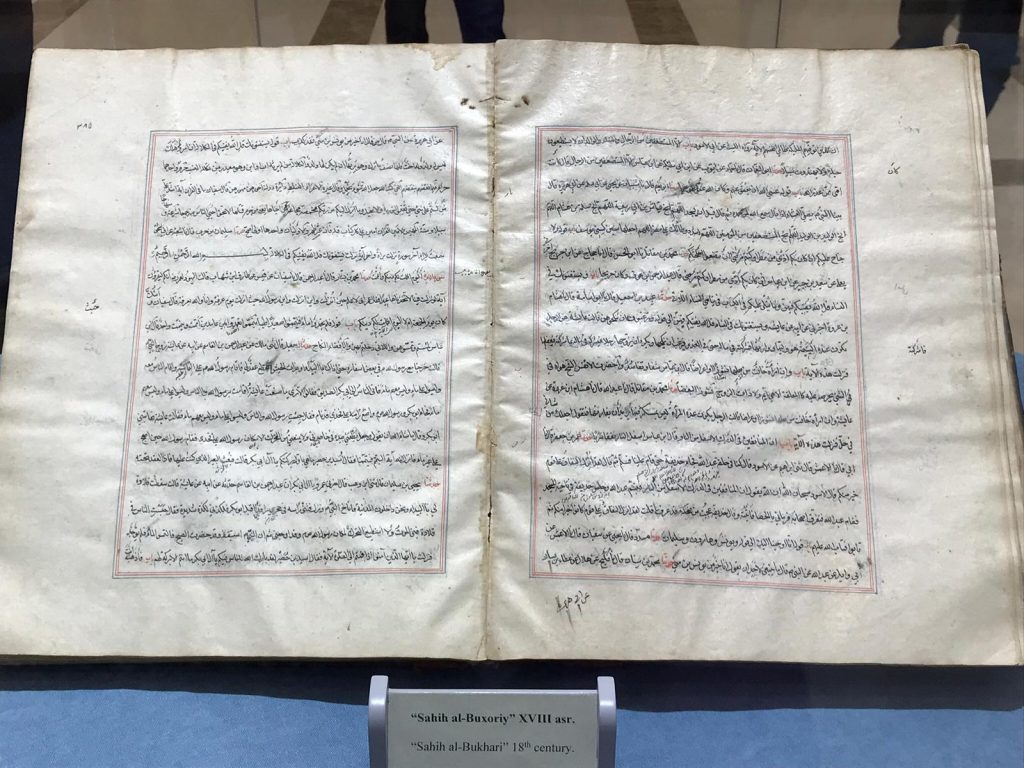

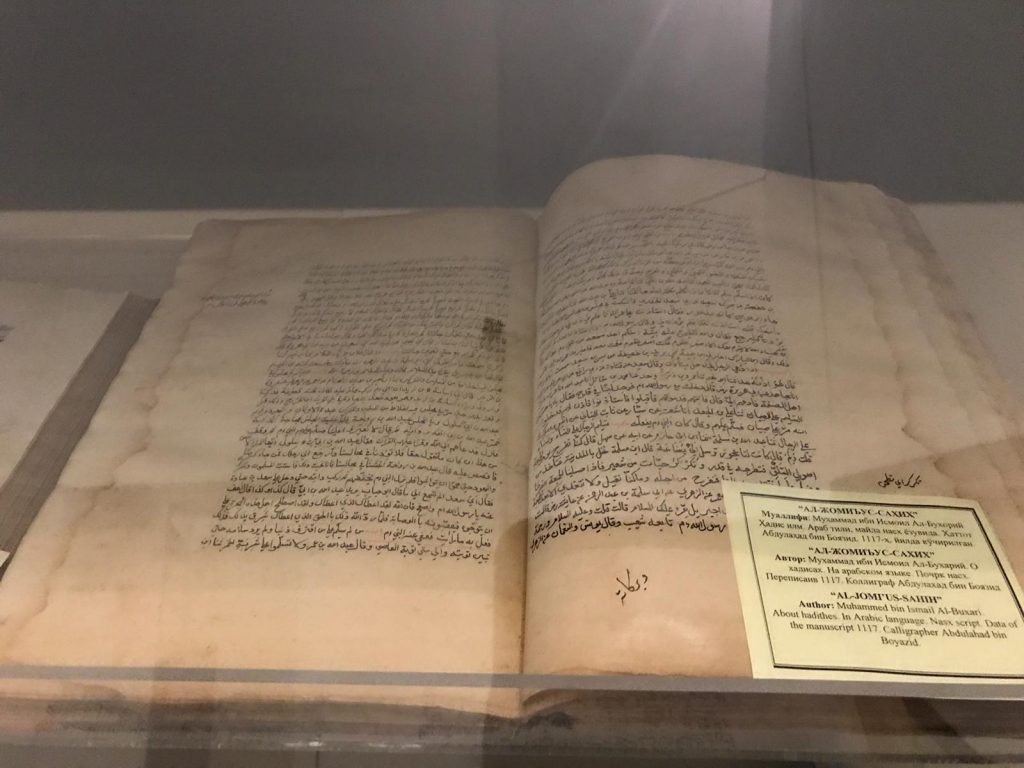

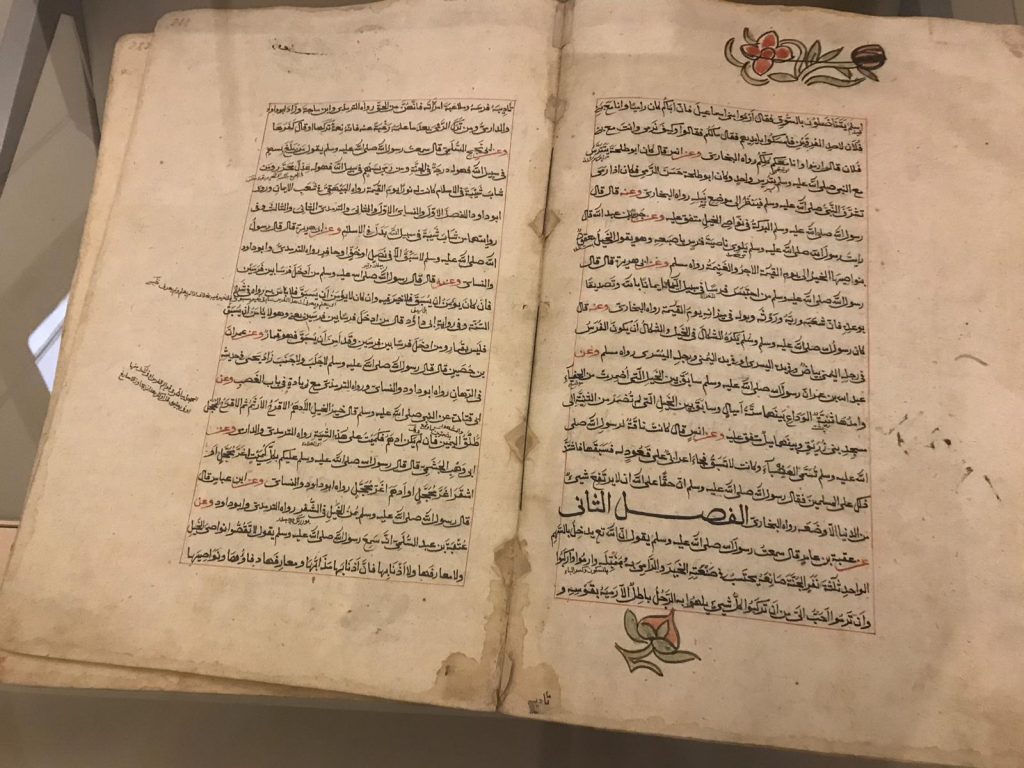

Next, we visit Markaz al-Imam al-Bukhari, which is home to a collection of manuscripts and old copies of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī.

Students and teachers have also gathered here. The Thulāthiyyāt narrations of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī are read by Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani, Dr Mawlana Imran Ashraf Usmani and Mufti Shabbir Ahmed. This is followed by a speech by Mufti Ṣāḥib focusing on three key messages. Mufti Ṣāḥib begins by highlighting that this is one of the most pleasant moments of his life. Imam Bukhārī travelled 1400km in the pursuit of knowledge.

His book is unanimously the most authentic book after the book of Allah. This is a miracle of Islam that all Muslims, Arabs and non-Arabs regard him – a non-Arab – the highest authority in the field of ḥadīth, despite the language of the Qurʾān and the ḥadīths being Arabic. Second, Mufti Ṣāḥib thanks the President for establishing this centre, which will inshāʾ Allah revive the ḥadīth and Islamic sciences here once again. The centre was established two months ago and we are among is first visitors. Third, Mufti Ṣāḥib explains that the reason for Imam Bukhārī’s success is not his profound knowledge alone, rather his piety and abstinence are central to this. He performed at least 14,000 rakʿat Ṣalāh whilst authoring his Ṣāḥīḥ. Acceptance is from Allah Almighty. The congregation is advised to keep this third point in mind when studying the Ṣaḥīḥ.

Within the complex, there is also a Madrasah that specialises in ḥadīth studies. The state-of-the-art building comprises of classrooms, dormitories, a canteen and also a swimming pool. It is an impressive setup. A short dars of Muwaṭṭāʾ is rendered here by my respected father Mufti Shabbir Ṣāḥib.

Ulugh Beg Observatory

We return to Samarqand and visit the Ulugh Beg Observatory shortly before midday. It was built in 1420 CE by the Timurid astronomer and leader Ulugh Beg (d. 853/1449) and was one of the finest observatories in the world. It was destroyed in 1449 and rediscovered in 1908. The guide explains that Ulugh Beg was the first person to measure the sky and determine the equator, 400 years before Greenwich. Here, the most important astronomical instrument is a large arch that would be used to determine midday (niṣf al-nahār). A trench of about 2 metres wide was dug in a hill along the line of the Meridian and in it was placed the arc of the instrument. A circular base shows the outline of the original structure and the doorway leads to the remaining underground section of the Fakhrī sextant that is now roofed over. The sextant was 11 metres long and once rose to the top of the surrounding three storey structure although it was kept underground to protect it from earthquakes. Calibrated along its length, it was the world’s largest 90-degree quadrant at the time, with a radius of 40.4 metres. The radius of the meridian arc was approximately 50 metres. It was used for the observation of the Sun, Moon, and other stars. Along with other sophisticated equipment such as an armillary and an astrolabe, the astronomers would determine midday according to the meridional height of the Sun, distance from the zenith and declination.

Mufti Ṣāḥib mentions that Mufti Rasḥid Aḥmad Ludyānwī (d. 1422/2002) was an expert of astronomy and taught Mufti Ṣāḥib this subject among others.

Opposite the Observatory is the Ulugh Beg Observatory Museum which was built in 1970 to commemorate its founder. The museum contains reproductions of his works as well as astrolabes and some other instruments.

Grave of Imam Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī

Our next stop at 12.20pm is the memorial complex wherein lies the grave of the famous ḥanafī jurist and theologian, Imam Abū Manṣūr Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn Maḥmūd al-Māturīdī (d. 333/944), the founder of the Maturidi school of theology and creed. He is described as “the Imam of guidance”. He authored several books including Kitāb al-Tawḥīd and Taʾwīlāt al-Qurʾān and passed away in Samarqand (al-Jawāhir al-Muḍiyyah, 2:130, 344; Tāj al-Tarājim, p.249).

As we enter the complex, Mufti Ṣāḥib highlights that the solid structure housing the grave did not exist in 1992. The grave is surrounded by several grave stones. A local guide explains that this area was originally part of a twenty-acre graveyard known as Jokardeza Graveyard. Only jurists were allowed to be buried here on the condition that their name was Muḥammad or Aḥmad. Given the significance of the graveyard, when Imam Bukhāri passed away 30km away, there was some discussion regarding burying him here. In the end, it was decided to bury him in Khartank where he passed away in accordance with the Sunnah, this was because he was regarded the flagbearer of the Sunnah and should be treated accordingly. It was sad to learn that when the Soviets occupied this region, they built a house for a Jewish family over the grave of Imam Maturidī, the Jew had two dogs named Adam and Eve. Of the twenty acres, only three acres have been restored to date.

Masjid Khoja Ubaydullah Ahrar

We perform Ẓuhr Ṣalāh in Masjid Khoja Ubaydullah Ahrar, which is next to the graveyard wherein lies the grave of Shaykh ʿUbaydullāh Aḥrār (d. 895/1490). He is the disciple of Shaykh Yaʿqūb Charkhī (d. 851/1447) who is buried in Tajikistan. Mufti Ṣāḥib has visited his grave. Shaykh ʿUbaydullāh’s disciple is Mawlānā ʿAbdurraḥmān Jāmī (d. 898/1492) as well as Shaykh ʿAbdullāh Yemeni as mentioned above. Shaykh ʿUbaydullah was a reformer whose approach was similar to that of Mujaddid al-Alf al-Thānī, Shaykh Aḥmad Sarhindī (d. 1034/1624). He would work with the rulers of the time to bring about change in the society using the top-down approach. He would avoid making the general masses take bayʿat on his hands, and would remark that if I was to start, then no saint would have any murīds (spiritual pupils) left.

As we walk out of the graveyard, I ask Mufti Ṣāḥib regarding a good book that details the life of Sufi saints from later generations. He mentions the book: Nafaḥāt al-Uns. Mufti Ṣāḥib is asked regarding the recitation of the Qurʾān at graves, whether it should be audible or not. The Salām should be audible and the Qurʾān should be read silently, he says. I ask Mufti Ṣāḥib regarding conveying Salām at graves on behalf of other people. He answers that this practice is established for the Prophet ﷺ, and suggests that perhaps qiyas can be done upon this for others. One of my very learned and special teachers yesterday sent me a message from the UK to convey his Salāms at the graves of the Imams.

Economy and deprivation

We return to our hotel, Regestan Plaza. Imam Zaynuddin provides insight into the economic condition of the country. There are gold and petrol mines. Gas is very cheap. Farming is common and there are also many factories.

Over the past few days, our limited observations suggest that the people are hard working. Poverty appears to be minimal in the urban areas, however, there is poverty in the rural areas. We have not come across anyone begging. My respected father highlights the need to build Masjids especially in the villages, and that it is a big bounty from Allah in the UK, Pakistan, India and elsewhere to have the freedom to build Masjids and preach therein with autonomy.

Grave of Qutham ibn al-ʿAbbās (may Allah be pleased with him)

Later in the evening, we head towards the graveyard of Qutham ibn al-ʿAbbās (d. 57/676-7, may Allah be pleased with him), the cousin of our beloved Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ. He resembled the Prophet ﷺ the most and was the final person to come out from his Laḥd grave. He was martyred in Samarqand during the conquest of the city under the leadership of Saʿīd ibn ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān (d.ca. 62/682) in the era of Muʿāwiyah (d. 60/680, may Allah be pleased with him). There are no ḥadīths transmitted from him in the six ḥadīth collections (Siyar, 3:440). Mufti Ṣāḥib makes a pertinent point that the differences between the Umayyads and the Banū Hāshim did not stop Qutham (may Allah be pleased with him) to work under and follow the instructions of the companion Muʿāwiyah (may Allah be pleased with him).

What is also interesting is that he is the only and final companion to have passed away in Samarqand. His brother ʿAbdullāh ibn ʿAbbās (d. 68/687-8, may Allah be pleased with him) shares a similar uniqueness in that he was the final companion to have passed away in Taif, Saudi Arabia, as outlined in my treatise regarding the final companions to have passed away.

As we approach the grave complex in the Shahi Zindah area, we enter via a graveyard to avoid a long staircase. This graveyard has graves from the Soviet era with facial images on each gravestone. Imam Zaynuddin explains that this practice no longer exists. The complex was built in the 10th century although it has been renovated recently.

After spending some time at the grave, we perform Maghrib Ṣalāh in the Masjid neighbouring the grave. Mufti Ṣāḥib leads the Ṣalāh and also delivers a speech. He says, “It is a great honour for this land to have a companion buried here.” He praises the efforts of Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq and Dar al-Hilal (see day 1) and makes particular mention of the translation of the nine ḥadīth books including Maʿānī al-Āthār and both Muwattāʾ.

As we return to the hotel, Mufti Ṣāḥib shows us a translation of one of the volumes of his Iṣlāḥī Khuṭubāt in Uzbek. This demonstrates two things; Mufti Ṣāḥib’s wide spread acceptance and the positive religious change in the country.

Registan

Later in the evening, some colleagues visit the Registan, which was at the heart of the ancient city and was home to some Madrasah, whilst some of us decided to rest.

Yusuf Shabbir

Samarqand, Uzbekistan

Day 5 – Wednesday 17 April 2019

From Samarqand to Termez

Samarqand requires at least two to three days; however, our time is limited. We are unable to visit the grave of the famous ḥanafī jurist and saint Faqīh Abū al-Layth al-Samarqandī (d. 373/983) who, it is suggested, is buried here. Mufti Abdurrahman Mangera who has a PhD on his Nawāzil suggests that he may have been buried in Balkh (currently in Afghanistan) where he spent the latter parts of his life. His Nawāzil, by the name of al-Fatāwā min Aqāwīl al-Mashāʾikh, has been published recently correctly by Darul Kutub al-Ilmiyyah. The Nawāzil book published prior to this was wrongly attributed to him, as outlined in detail by Mufti Abdurrahman Mangera in his thesis which is available online with parts of Nawāzil therein. Other published works of Faqīh Abū al-Layth include: Tanbīh al-Gāfilīn and Bustān al-ʿĀrifīn, both are published (Siyar, 16:322; al-Jawāhir al-Muḍiyyah, 2:196).

We depart from Samarqand at 9.30am and head south towards Termez, a city that lies on the border of Afghanistan. The distance between Samarqand and Termez is 375km. The route is very scenic, navigating our way through the mountainous region. The weather is also very good unlike the previous two days. However, it is a bumpy ride. The road infrastructure requires improvement.

We stop at 12pm at a local town by the name of Kitab in the Qashqadaryo province. Mufti Ṣāḥib delivers a brief speech here at the Madrasah Xoja Buxoriy (Khawajah Bukhari), which is named after a local pious Naqshbandī saint. Mufti Ṣāḥib advises the students to work hard and act upon the knowledge that is acquired.

We proceed from here to the village of Yakkabog in the same province where the locals have prepared lunch for us. Timur Lung was born here. It is 1pm. The people are extremely hospitable in this country. We eat, perform Ẓuhr Ṣalāh and continue the journey to Termez.

Būg, the resting place of Imam Tirmidhī

Our first stop before arriving in Termez city is Būg, now known as Cumisli (pronounced: Chumuslī). This is where Imam Tirmidhī (d. 279/892) is buried. Imam Tirmidhī requires little introduction. He is the author of the famous Sunan and al-ʿIlal. His teachers include Imam Bukhārī whose views he frequently cites in his Sunan. Imam Bukhārī also heard some ḥadīths from his student, as mentioned in the Sunan. Both enjoyed a close relationship. He became blind towards the end of his life due to crying and passed away in Termez (Siyar, 13:270).

As we enter the recently built complex wherein lies the grave of Imam Tirmidhī, a large group of people await us. It is a very emotional moment as we stand around the grave reciting and supplicating for the Imam. Mufti Ṣāḥib reads the one and only thulāthī narration of the Sunan. Mufti Muhammad ibn Adam and Dr Mawlana Ashraf Usmani read the first ḥadīth, and later this is also read by his son Abdullah and Mawlana Faruq Pandor’s son. Mufti Ṣāḥib makes a short supplication facing the Qiblah. Tears are flowing from the eyes. Mufti Ṣāḥib requests all present to supplicate that Allah Almighty forgive his errors in his commentary of the Sunan. He adds that he has gifted the reward of all his efforts on the Sunan to Imam Tirmidhī. This is significant. My respected father says to Mufti Ṣāḥib that we have all benefited from Dars Tirmidhī and Taqrīr Tirmidhī and supplicates for Mufti Ṣāḥib’s health and well-being. Mufti Abdurrahman Mangera, Mufti Muhammad ibn Adam, Mawlana Faruq Pandor and I studied the entire Tirmidhī with my respected father in Darul Uloom Bury. Mufti Muhammad also studied the first volume with Mufti Muhammad Taqi Ṣāḥib. This is a unique honour to travel with your teachers to such places. This is also the first time Mufti Ṣāḥib has visited this place, as in his previous visit he did not visit Termez.

We perform ʿAṣr Ṣalāh at the Masjid within the complex. Mufti Ṣāḥib delivers a short speech thereafter providing a brief commentary on the two parts of the first ḥadīth of the Sunan. An emphasis is made on outer purity by learning fiqh and inner purity by remaining in the company of pious people, along with acquiring wealth via lawful and pure means.

There is also a large cemetery within the outer compound. This has many graves with each grave having a simple headstone. This is the more correct way as opposed to building large solid structures.

As we leave the complex, Mufti Ṣāḥib is gifted some books by Mirza Ahmad Khushnazar, a local 63-year-old scholar who has translated the Sunan, the Shamāil, and a book on the profiles of tirmidhiyyūn (scholars of Tirmidh). There are signs of nobility on him.

Before we board the car, something strange occurs. A person comes to me as well as a few of our colleagues and attempts to give us monetary gifts. We politely refuse. It is remarkable because in most other countries, people ask visitors for money particularly at graves.

The resting place of al-Ḥakīm al-Tirmidhī

Our next stop is the resting place of al-Ḥakīm al-Tirmidhī (d.ca. 320/932), the pious saint, ḥadīth scholar and author of Nawādir al-Uṣūl, which has been published in recent years in five volumes with the asānīd of the narrations. The beauty of this ḥadīth collection is that the ḥadīths are accompanied with brief commentary. However, the book contains many extremely weak narrations and a person should verify the status before using any ḥadīths from therein. He also has certain isolated opinions (Siyar, 13:439).

The beautifully built complex is a 45-minute drive from Būg, very close to the border with Afghanistan. We arrive at 7.30pm, perform Maghrib Ṣalāh and spend some time at the grave. Unlike all other graves we have visited that are totally separate from the Masjid, his grave is next to the first few rows of the Masjid to the left and is only accessible from the main prayer hall. Mufti Ṣāḥib grants the writer permission to read the first ḥadīth of Nawādir al-Uṣūl.

Termez

We head towards Termez city which is not far and arrive at the Silk Road Hotel at 8.30pm. Termez is situated in the most southern part of the country near the Hairatan border crossing of Afghanistan. It is the hottest point of Uzbekistan and the weather here is very hot. Its population exceeds 140,000. Like the rest of the country, it is very clean. It is next to the Amu River (Jayḥūn) which according to a ḥadīth is from among the four rivers of Paradise (Musnad al-Bazzār, 8199). Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī (d. 622/1225) in Muʿjam al-Buldān (2:26) describes it a famous city, which is surrounded by a wall and that is market is furnished with bricks. He mentions some scholars who were from Tirmidh. They include the teacher of Imam Tirmidhī, Imam Abū al-Ḥasan Aḥmad ibn al-Ḥasan ibn Junaydib (d. after 240/854), also referred to as al-Tirmidhī al-Kabīr. He is also Imam Bukhārī’s teacher (Siyar, 12:156). We ask a local scholar if the location of his demise is known. He is unaware. Based on the material available to me at the moment, I have been unable to ascertain his place of demise.

Although it has been a long tiring day today, we decide to take a quick tour of the city late in the evening as we will not have the opportunity tomorrow. However, we are advised to avoid this at this time of the evening because of the close proximity of the Afghan border.

Yusuf Shabbir

Termez, Uzbekistan

Day 6 – Thursday 18 April 2019

Return to Tashkent

We depart from our hotel at 8.30am and head to Termez Airport.

The 10am flight to Tashkent is slightly delayed. The one-way flight only costs £28. The distance between both cities is 700km. In hindsight, it would have been much easier to have travelled from Samarqand to Tashkent via the High-Speed Train and fly into Termez from Tashkent. As the plane takes off, we see the Amu River (Jayḥūn).

During this journey, I ask Mufti Ṣāḥib regarding his approach and main books when compiling Takmilah Fatḥ al-Mulhim. He explains that he would use the commentaries of Imam Nawawī (d. 676/1277) and ʿAllāmah Ubbī (d. 827/1423-4) along with Fatḥ al-Bārī, in addition to specific books on specific subjects. He would sit in the old library of Darul Uloom Karachi which barely had space to sit. In relation to a question regarding effective note taking when reading books, Mufti Ṣāḥib advises to keep a file divided into subject areas, for example, purity, Ṣalāh and so forth, and record any new learning points therein. If in a rush, just note the reference. The second and third volumes of Tarāshey will be published soon. Mufti Ṣāḥib explains in relation to his writings that he is only the means, Allah Almighty is the one who grants tawfīq. When a person writes with a pen, it is the pen that writes, however, the writing is attributed to the person. Similarly, when a person authors a work, it is Allah Almighty who makes it happen. The issue of the impermissibility of the prevalent pet food in western countries is also discussed.

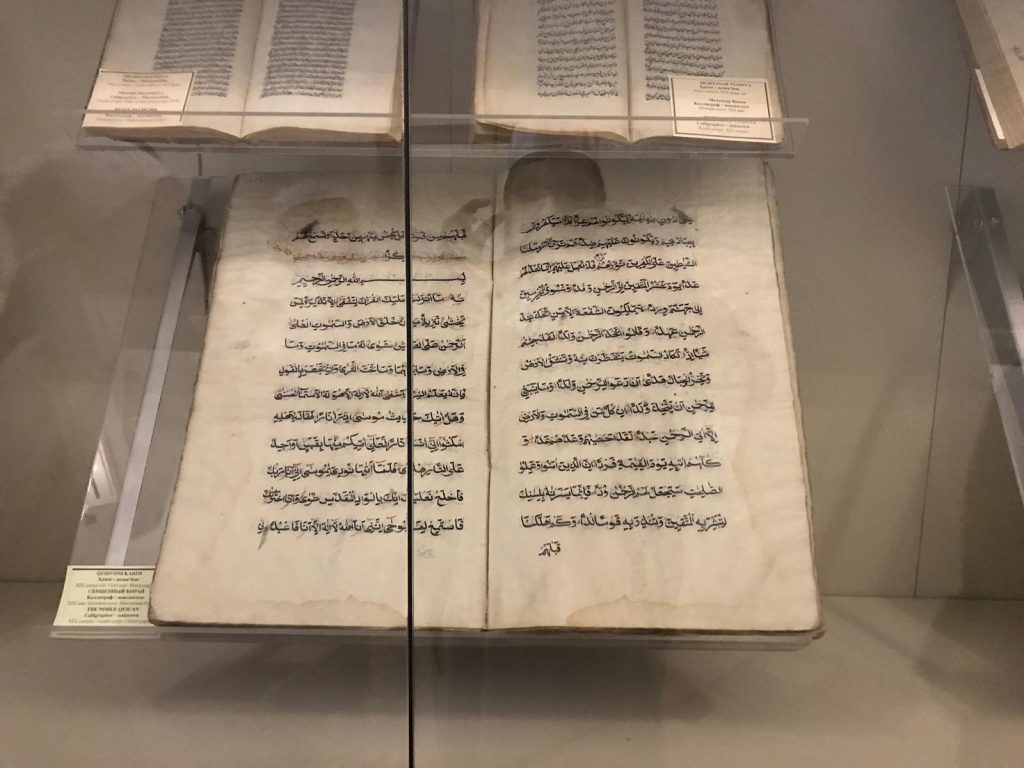

Al-Muṣḥaf al-ʿUthmānī

We arrive at Tashkent International Airport at 11.30am and head straight to the Hast Imam Library which is home to a Muṣḥaf claimed to be from the era of ʿUthmān (d. 35/656, may Allah be pleased with him). It is written in Kufic script without dots. ʿAllāmah Muḥammad Ḥamīdullāh (d. 1423/2002) provides a unique insight into this Muṣḥaf in Khuṭubāt Bahāwalpūr (p.26).

There are also manuscripts of other books here.

Tomb of al-Qaffāl al-Shāshī

Next, we head towards the resting place of the famous Shāfiʿī jurist Imam Abū Bakr al-Qaffāl al-Shāshī (d. 365/976). It has already been mentioned in the account of Day 1, that the residents of Tashkent were Shāfiʿīs unlike the rest of Transoxiana, this appears to have been the situation for several hundred years. There are no Shāfiʿīs here now. Imam Qaffāl was a very senior scholar of his era. Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī (d. 748/1348) describes him as Imam, ʿAllāmah, Faqīh, Uṣūlī, the scholar of Khorasan, the Imam of his era in Transoxiana. He is also known as al-Qaffāl al-Kabīr and travelled in the pursuit of ḥadīths. Ḥadīth experts such as Imam Ḥākim (d. 405/1014) transmit ḥadīths from him (Siyar, 16:283). He authored many books and passed away here in Tashkent.

We enter the mausoleum which is home to his grave, recite and supplicate and do similar at several other graves within the complex of some scholars of the 20th century.

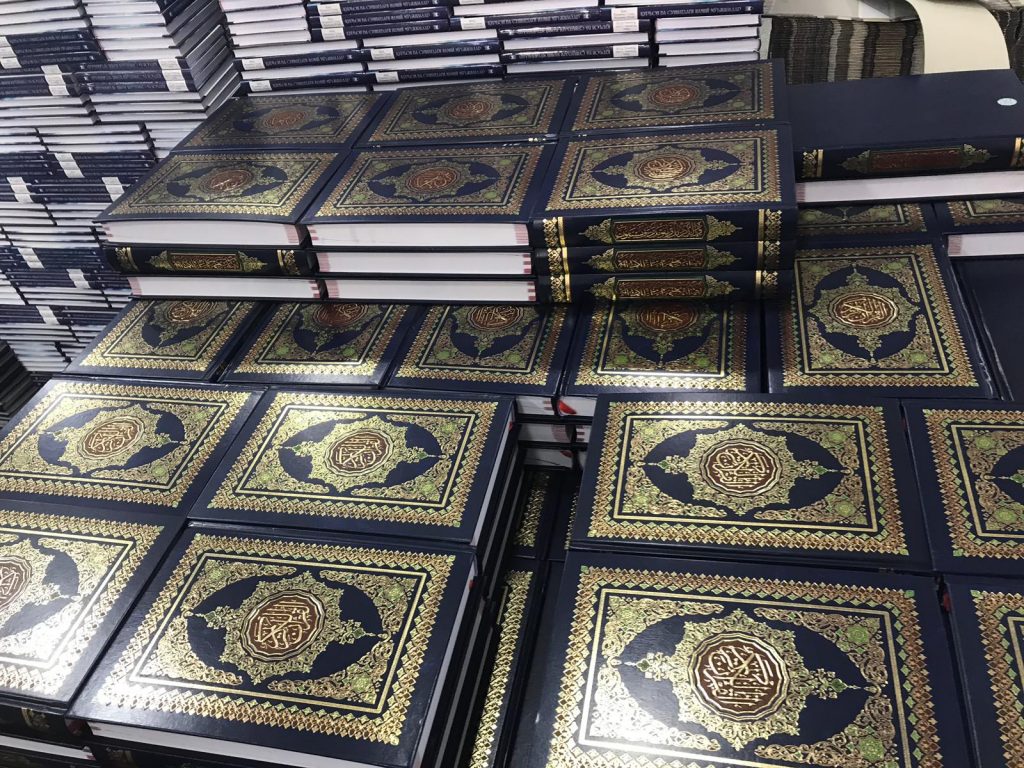

Dar al-Hilal and the Muṣḥaf Project

Later in the evening, we visit the headquarters of Dar al-Hilal, which specialises in the designing, printing and selling of Islamic books in Uzbek and Russian, as outlined in the account of Day 1. The organisation is the first in the country to publish Muṣḥafs. Until now, Muṣḥafs were imported from outside he country and would cost the end user $10 USD each. The organisation has taken it upon itself to publish Muṣḥafs in-house and sell it for $3.75 USD at cost price. Two days later on Saturday, they plan to sell the Muṣḥafs. Hundreds of customers will come and the road outside will have to be closed. This demonstrates the value and respect of the Muṣḥafs among local people.

Currently, the organisation prints 100,000 books across a range of subjects every month. After relocating to a larger venue, this will increase to 250,000 books per month, with a dedicated section for printing Muṣḥafs, the plan is to print 25,000 Muṣḥafs every month. Subḥanallāh, there was a time, when it was prohibited to read the Muṣḥafs and people struggled to find a Muṣḥaf. This is a great service to the community. The organisation has received national awards twice for binding, and five books of Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq, the founder, have also won awards. The organisation also sells Islamic books printed by other publishers. It is in this section we note that parts of Badāʾiʿ al-Ṣanāʾiʿ have been translated in Uzbek.

Shaykh Muḥamamd al-Ṣādiq’s son, Shaykh Ismāʿīl explains the reason behind establishing the in-house printing facilities. Some printers would refuse to print Islamic publications whilst others would deliberately create difficulties and cause delays.

Ijāzah of ḥadīth programme

After touring the printing facilities and learning about the books published and sold by Dar al-Hilal, the Ḥadīth Ijāzah programme commences. Over 300 students and scholars have gathered. The entire al-Awāʾil al-Sunbuliyyah collection of ḥadīths is read by Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani, my respected father, Dr Imran Ashraf Usmani, Shaykh Ismāʿīl and the humble writer. This is followed by a speech by Mufti Ṣāḥib in Arabic. The summary of the speech is as follows:

“I met Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq on many occasions in international conferences. However, I did not realise the extent of his knowledge and his works until this visit today. I grant you ijāzah, although I am not worthy of it, for blessing and to fulfil the instructions of colleagues. My thabt (containing my asānīd) will be published shortly.”

He proceeds to say, “I wish to share with you a glad tiding and some advice. The glad tiding is that we at Darul Uloom Karachi have embarked on a project to codify and gather all the Prophetic ḥadīths into one compilation with a global referencing and numbering system. We have used 960 published and non-published works and gathered 70,000 ṭuruq (routes) thus far. The first volume comprising of the book of faith is published and the second, third and fourth volumes will be published soon covering the chapters of knowledge, holding onto the Qurʾān and Sunnah, and purity. The advice is that acquiring knowledge on its own is not beneficial, it must be accompanied with action. The primary purpose is to follow the Sunnah in all areas of life. Many non-Muslim orientalists have more knowledge than many Muslims, however, their knowledge is of little benefit. A person who wishes to act upon the knowledge should remain in the company of scholars and pious people and always have the intention to please Allah Almighty.”

The programme is concluded with a Khatm (completion) of the Qurʾān by a middle-aged man. He recites the final and beginning of the Qurʾān in a melodious tone. Mufti Ṣāḥib explains this practice in light of the ḥadīth of Sunan al-Tirmidhī (2948) which indicates that a person should continue with his recitation and therefore start the next Qurʾān recitation immediately after one has been completed.

The programme is followed by a meeting with Banking Professionals interested in Islamic Finance. This is followed by a feast prepared by a local associate of Shaykh Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq at his house. The people here are extremely hospitable and show immense gratitude and respect for scholars and guests. Mufti Ṣāḥib cites some Persian poetry and comments that it is as though the Persian language was created for poetry. It appears that Persian is more popular in Bukhara than Tashkent.

Yusuf Shabbir

Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Day 7 – Friday 19 April 2019

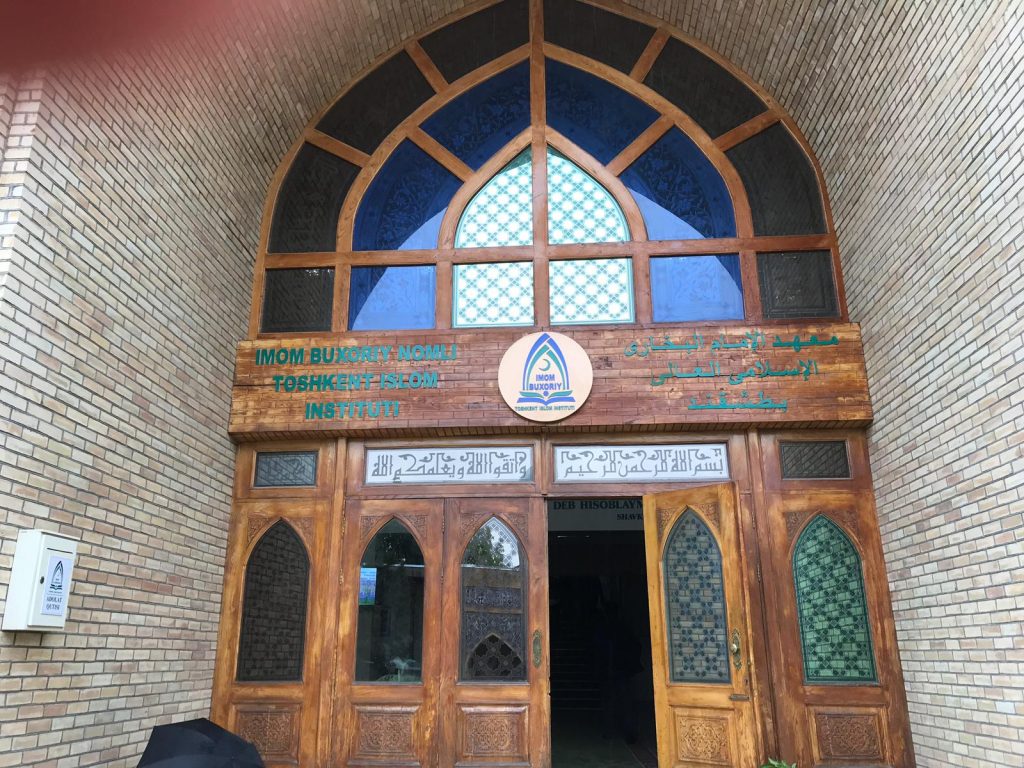

Meeting with Grand Mufti and visit to Maʿhad al-Imam al-Bukhārī al-Islāmī al-ʿĀlī

Meeting with Grand Mufti

The morning begins with a meeting with the Grand Mufti of Uzbekistan, 66-year-old Shaykh Usman Khan ibn Timur Khan Alimov. He was appointed Grand Mufti twelve years ago. During the Soviet era, he served as Imam of Masjid al-Bukhārī in Samarqand for thirty years.