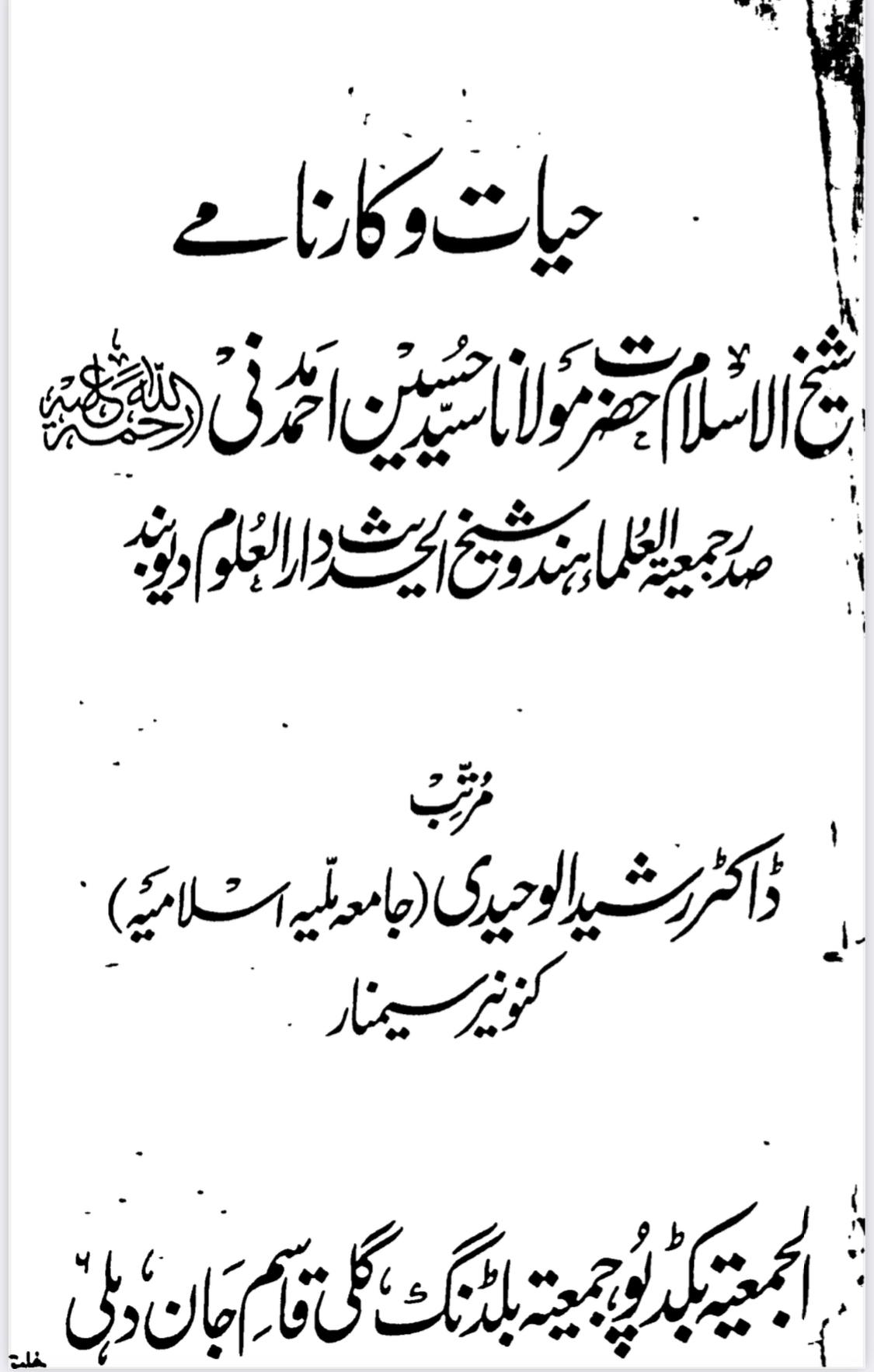

An amazing book on Shaykh al-Islām Mawlānā Ḥusayn Aḥmad Madanī (d. 1377/1957)

Shaykh al-Islām Mawlānā Ḥusayn Aḥmad Madanī (d. 1377/1957) is among those personalities whose mention brings about a sweetness in the mouth, which is difficult to describe. It should therefore not come as a surprise that when I came across the Urdu book Ḥayāt wa Kārnāmey Shaykh al-Islām Ḥaḍrat Mawlānā Sayyid Ḥusayn Aḥmad Madanī Raḥmatullāhi ʿAlayh compiled by Dr Rashīd al-Waḥīdī, Professor of Jamia Millia Islamia and graduate of Darul Uloom Deoband, I read it within two days. The 512-page book features more than 40 articles authored by different scholars for a seminar on the life and achievements of Shaykh al-Islām that was held in India on 18-19 March 1988. Having read several works on this great Imam, revolutionary and leader of the 20th century particularly when visiting Malta and also having proofread the English abridged version of the autobiography Naqsh Ḥayāt, this book is among the best, filled with invaluable pearls and priceless gems.

One of the outstanding articles featured therein is by Shaykh Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī al-Nadwī (d. 1420/1999) who has succinctly explained the role of the British in destroying India and the Ottoman caliphate and the disastrous impact of this on Islam and Muslims. This context is not only vital to appreciate the contribution and sacrifice of Shaykh al-Islām, it is also important for the preservation of Islam and Muslims in the future, both here in the UK and beyond.

Whilst reading through this collection, I made note of several points of interest which are summarised here under some interlinked sub-headings for the benefit of our readers who do not understand Urdu.

Leadership and Politics

- Shaykh al-Hind Mawlānā Maḥmūd Ḥasan Deobandī (d. 1339/1920) stressed that it is permissible to work together with non-Muslims to liberate India, as long as the religious rights of Muslims are not impacted (p.70, 278-279). This is important. If Shaykh al-Hind and Shaykh al-Islām were alive today, would they have adopted the same strategy as they did then? This is a matter of discussion.

- Shaykh al-Hind advised Shaykh al-Islam: “Do not ever stop teaching, even if you only have one or two students” (p.163). One of the reasons behind Shaykh al-Hind’s success was that he had developed a network of passionate and committed students and scholars who continued his mission whilst he was incarcerated and also after his demise (p.179).

- Shaykh al-Islām would deliver a lecture once a week on history, politics, economics and geography and provide his insight into current affairs (p.66, 105). Masjids in the western world should organise regular events, highlighting the situation of Muslims in different countries, for example, by focusing on a different country each month. Remaining connected and concerned with the Ummah is a central highlight of Shaykh al-Islām and Shaykh al-Hind’s life-long mission.

- Along with religious sciences, Shaykh al-Islām would highlight the importance of the worldly sciences and their benefits (p.133). He himself studied history and geography in school in his early life, which played a role in the development of his ideology and life-long work.

- Shaykh al-Islām was prisoned cumulatively for approximately 7 years and 9 months, throughout his 81-year life (p.157).

- The Algerian scholars and freedom fighters, Shaykh Muḥammad al-Bashīr al-Ibrāhīmī (d. 1385/1965) and Shaykh ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd ibn Bādīs (d. 1359/1940) were students of Shaykh al-Islam and drew inspiration and guidance from him in their liberation struggle (p.168 – 175). The lesson for us is that we should have concern for our brothers and sisters all over the world, not just in our country. Whilst claiming to be heirs of such luminaries, we have become selective and only take from them that which keeps us confined to our comfort zones. Shaykh al-Islām’s life was all about staying out of the comfort zone. He would advise his associates to be prepared at all times (p.250). In his youth, he would undergo physical training for example by walking barefoot in the extreme heat for several hours, and when asked he remarked, “We will have to face more severe hardships in prison in future” (p.402). This should not come as a surprise, because Shaykh al-Hind would take Bayʿat upon physical struggles as mentioned in Naqsh Ḥayāt (2:203). Another example of being selective is worth mentioning. Some people object to undertaking protests in the UK and elsewhere to highlight the plight of Palestinians and for other causes, suggesting it is not from the Sunnah or the practice of the elders. However, there are many ḥadīths pertaining to enjoining good and forbidding from evil via the tongue (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, 49), and speaking the truth in the presence of an oppressive ruler has been described as the most virtuous Jihad (Sunan al-Nasāʾī, 4209; Sunan al-Tirmidhī, 2174; Sunan Ibn Mājah, 4011-2). In so far as the elders are concerned, Shaykh al-Hind said: “As modern weaponry is lawful to repel the enemy despite not existing in previous eras, there is no hesitation in the permissibility of protests and joint political acts, because for those who do not have weapons, these are the only weapons” (Naqsh Ḥayāt, p.679).

- In 1923, Shaykh al-Islām made the demand for total freedom from British rule at a time when the Indian National Congress were only demanding home rule. It was six years later in 1929 that the Indian National Congress demanded total freedom (p.361).

- Shaykh al-Islām predicted that Islamic laws will not be implemented in Pakistan (p.389). Notwithstanding a few laws and some provisions within the constitution, the vast majority of the legislative and judicial processes and machinery of government and education systems are based on the British system.

- Shaykh al-Islām was of the view that Muslims should marry four wives and have many children, and thereby increase the population and become a majority (p.124).

Personality

- Shaykh al-Islām was very humble and would dislike people standing up for him (p.80, 316, 410). According to him, the ḥadīth “Stand up to your leader” (قوموا إلى سيدكم) was to aid and support Saʿd ibn Muʿādh (d. 5/627, may Allah be pleased with him), not out of his reverence. The issue and the difference of opinion in this regard is briefly discussed in al-ʿIqd al-Thamīn fī Ḥubb al-Nabī al-Amīn ﷺ (p.537). Mawlānā ʿAbd al-Mājid Daryābādī (d. 1397/1977) writes that Shaykh al-Islām’s miracle was his humility, modesty, selflessness, and sacrifice (p.303). He further marvels at Shaykh al-Islām’s hospitality and going out of his way to personally attend to the needs of guests (p.308). This hospitality was renown and continues to runs in the family, as I have experienced several times at the residence of Shaykh al-Islām’s son Sayyid Mawlānā Arshad Madanī (b. 1360/1941) and grandson Sayyid Mawlānā Maḥmūd Madanī (b. 1383/1964) in Deoband, as outlined in my travelogues.

- In relation to Shaykh al-Islām’s humility, on one occasion, whilst travelling on the train, his assistant needed the toilet. He went but returned as it was very dirty. Shaykh al-Islām sensed that he did not relieve himself for this reason, so after a short while he himself went to the toilet and cleaned it. He returned and told his assistant to use the toilet (p.306). Shaykh al-Islām would travel in the third-class train carriage (p.313).

- Shaykh al-Islām was extremely particular about fulfilling promises (p.311).

- Whenever Shaykh al-Islām would request something, he would insist on paying for it (p.138).

- Throughout his life, Shaykh al-Islām was offered various roles but declined them. They include the role of Shaykh al-Ḥadīth in Azhar University. He was also offered a role in Dhaka University (p.313, 409).

Darul Uloom Deoband

- It is suggested by some that in the period between the demise of Shaykh al-Hind and Shaykh al-Islām re-joining Darul Uloom Deoband, the institute was indirectly under the patronage of British rulers (p.103). In difficult times, difficult judgements have to be made, and sometimes mistakes are also made. Individuals within institutions sometimes, with all good intentions and without any malice, make judgements based on what they think is in the best interests of the institution. Ḥusn Ẓann is vital, however the truth should not be sidestepped. This is mentioned because sometimes the protection, or presumed protection, of organisational interests results in certain compromises. In the UK context, contentious issues for example on sexuality are no longer being discussed on the pulpit in the way that they should be, and certain Fatwas will no longer be issued by institutes. It is a difficult balance, but one cannot deny that we are being silenced and the current trend is set to have disastrous consequences.

- Shaykh al-Islām agreed to return to Darul Uloom Deoband to teach on the condition that his travels and efforts for the liberation struggle would continue (p.122). Mawlānā Ashraf ʿAlī Thānawī (d. 1362/1943) and others in the management accepted this and all of his other conditions, which also included “Whatever information reaches you about me, you will seek clarification from me directly before forming a judgement”, “I will have nothing to do with those matters of the Madrasah which are based on cooperation with the Government” (p.496 for the other conditions).

- One of the article writers is critical of the two-volume book Tārīkh Darul Uloom Deoband for failing to detail the reasons why ʿAllāmah Anwar Shāh Kashmīrī (d. 1352/1933) and others left Darul Uloom and also for failing to adequately cover Shaykh al-Islām’s role and contribution in filling the void (p.375). Sometimes there is benefit in sharing uncomfortable truths with adab (etiquette) so that future generations can reflect on them.

- Shaykh al-Islām would often return from long journeys late in the evening and teach (p.198), something one of Shaykh al-Islām’s living students, Mawlānā Bashir Diwan of Auckland mentioned to me a few months ago, as outlined in my travelogue entitled One month in New Zealand, Australia and Singapore.

- Shaykh al-Islām would always walk from his home to the Dār al-Ḥadīth, even in his final parts of life when walking was difficult for him (p.497).

- Shaykh al-Islām would teach Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī from the Egypt print of Irshād al-Sārī of ʿAllāmah Qasṭallānī (d. 923/1517) (p.443).

- During partition, Ḥakīm al-Islām Qārī Muḥammad Ṭayyib Ṣāḥib (d. 1403/1983) had migrated to Pakistan with the intention of staying there. Upon his arrival, he decided to return to Deoband. However, due to the political circumstances, it was difficult to return. Shaykh al-Islam personally met with Jawaharlal Nehru and obtained permission for him (p.253). He thus returned and continued as the rector of Darul Uloom Deoband.

Journeys within India

- Shaykh al-Islām travelled to Kokan and transformed the religious landscape there (p.126) leading to the establishment of Madrasah Ḥusayniyyah (p.134). During this journey, he would emphasise on two things – the beard and how it is a hallmark for Muslims and secondly the Quran (p.133).

- Similarly, his travels to Purnia district had a transformational impact (p.328). He had a habit of emphasising on the beard (p.331), something I have also observed in his son Sayyid Mawlānā Arshad Ṣāḥib. He would also emphasise on simple marriages and campaign against interest-based transactions.

Dealing with differences

- Shaykh al-Islām worked hard to rebut the false accusations laid out in Ḥusām al-Ḥaramayn (p.147).

- When Shaykh al-Ḥind Mawlānā Maḥmūd Ḥasan Deobandī wrote a letter to Mawlānā Aḥmad Raḍākhān regarding a debate, he addressed him therein “Jāmiʿ al-Ashtāt, Janāb Mawlawī Aḥmad Raḍākhān Ṣāḥib” (p.149).

- Separately, ʿAllāmah Iqbal (d. 1357/1938) had published some strongly worded poems against Shaykh al-Islām’s position, as the former championed the establishment of Pakistan. However, when he passed away, Shaykh al-Islām was in Delhi and he requested the congregation of thousands to supplicate for him (p.252). This was his habit that he would supplicate even for those who ridiculed him (p.315), a sign of his sincerity and clean heartedness.

- In 1936, many scholars of Deoband were involved in the takfīr of Mawlānā Shiblī Nuʿmānī (d. 1332/1914) and Mawlānā Ḥamīduddīn Farāhī (d. 1349/1930). Shaykh al-Islam’s habit was to fully research and verify any issue before reaching any conclusion, and he expected the same from others as mentioned above. Thus, he travelled from Deoband to Sarai Meer which is more than 700km away and personally investigated the matter. He concluded that both scholars were wrongly accused of things. He thereafter defended both, which upset some people (p.321; also refer to Kifāyat al-Mufti, 1: 343). Nothing would deter him from speaking the truth. He would also avoid writing forewords until thoroughly studying the content of the books (p.322).

- Lucknow had been the centre of Sunni Shiite disputes. Shaykh al-Islām was involved in some of the court proceedings. He was firmly of the view that unity with Shiites is not possible so long as they continue to degrade the hallmarks of Sunnis (p.426). He also made clear that the status of praising the companions is under normal circumstances mustaḥab (desirable), but this changes to wājib (necessary) when they are degraded (refer to Kifāyat al-Mufti 2: 171, 9: 282 for additional details).

Fiqh and Ḥadīth

- Shaykh al-Islām would not eat sitting on a chair and table (p.130). He was vehemently opposed to the English culture and their ideals and customs.

- It appears that Shaykh al-Islām would say Āmīn in Ṣalāh with a slight audible sound (p.193), combining between the narrations of Sirr (quiet) and Jahr (loud). Perhaps, this corresponds to what our respected Shaykh Muḥammad Yūnus Jownpūrī(d. 1438/2017) who was very fond of Shaykh al-Islām, describes in Nibrās al-Sārī (3: 225) as “Jahr Mutawassiṭ”, to reconcile between the narrations. I was aware that Shaykh al-Islām would recite Bismillāh loudly in Ṣalāh, something he has discussed in his Fatāwā (p.54) also, but was unaware about the Āmīn. I have thus today added it to my published copy of Al-ʿInāyah fī Taḥqīq al-Aḥādīth al-Garībah fī al-Hidāyah and also to the unpublished Irshād al-Qārī ilā Ikhtiyārāt Shaykhinā al-ʿAllāmah al-Muḥaddith Muḥammad Yūnus al-Jownfūrī.

- I have heard from our respected Mufti Aḥmad Khānpūrī Ṣāḥib (b. 1365/1946) that Shaykh al-Islam would read رضي الله عنه وعنهم when a Ṣaḥābī’s name would be mentioned in the Isnād, as also quoted in al-ʿIqd al-Thamīn fī Ḥubb al-Nabī al-Amīn ﷺ (p.278). The primary reference of this is in this book (p.186) which has also been added today.

There are many historical facts and experiences found in this collection, not found elsewhere. This is the advantage of such seminars wherein the experiences of various writers and their interactions and observations can be collated into one place, providing an all-rounded and multi-faceted insight into a personality. As I recently suggested to respected Shaykh Ahmad Ali of Leicester and respected Shaykh Khalil Ahmad Kazi of Dewsbury, that such a seminar is required in English on the life of our respected teacher Mawlānā Yusuf Motala Ṣāḥib Raḥimahullāh (d. 1441/2019) so that his personality, contribution and impact on British Muslims can be properly documented for future generations.

Mufti Kifāyatullāh Dehlawī Ṣāḥib

Returning to the book, another fact that caught my eye was that Mufti Kifāyatullāh Dehlawī (d. 1372/1952), a graduate of Darul Uloom Deoband and student of Shaykh al-Hind, was also imprisoned (p.106). He was the first President of Jamiat Ulema Hind. His role within Jamiat and the liberation struggle is not commonly known. He is more famous for his 9-volume Kifāyat al-Muftī. I have heard my respected father Mufti Shabbīr Aḥmad (b. 1376/1957) praise Mufti Ṣāḥib a lot and comment that his edicts reflect profound fahm (understanding).

One cannot deny that a person’s context, experiences of life and work shapes their thinking and also impacts on their views. For a considerable period, I wondered what shaped some of the views and edicts of Mufti Kifāyatullāh Ṣāḥib, such as the permissibility of taking (not giving) interest from banks and distributing it to the poor (1: 36, 8: 65, 77), Qunūt Nāzilah in all the Jahrī Ṣalāh (3: 444 – 452), permitting religious and worldly education for females in response to a question from Afghanistan 100 years ago (2: 66, 69), permitting a female in pardah to deliver a speech in a public protest (2: 69), voting for a local female Muslim candidate who observed pardah (9: 418), permitting an event in a Masjid jointly organised by Muslims and non-Muslims (3: 165), regarding three divorces as one in extremely desperate cases of risk of suicide or apostasy not otherwise (6: 355, 356), differentiating between the sin of shaving and trimming the beard (9: 172, 174, 178) and similar. Thereafter, when I read about his involvement in Jamiat Ulema Hind and the liberation struggle, the reason become clear. When a person remains confined to a Madrasah or Masjid setting with like-minded people, his life experiences and interactions are inevitably different from someone who is active in the socio-political work of the community and interacts with different groups of people. A person’s priorities and thinking are inevitably impacted. There are also geopolitical circumstances and the ground reality and the principle of the “lesser of the two evils” which has an impact. Sometimes there are also other factors such as the strength of evidence.

This point is highlighted because it is noticed in this age of social media that some people often fail to appreciate the context, are quick to pass judgements, whilst thinking or claiming that the elders were always uniform in their approach to jurisprudence. An example is shared here for reflection. I recently visited India and visited the Jamiat Ulema Hind office in Delhi, where there is a modern looking exhibition featuring the history of Muslims in India and the role of Muslim scholars and activists in liberating India. The exhibition includes photos of Shaykh al-Islam and other freedom fighters. I tweeted about this exhibition and also wrote about it in my travelogue.

Extremely impressed with the strategy, vision, professionalism, projects and office layout of Jamiat Ulema Hind. This short clip from the Jamiat office in Delhi. Allah protect the faith, honour and dignity of our brothers and sisters of India and all those striving for them. pic.twitter.com/x3htLoRXry

— Dr Yusuf Shabbir (@ibn_shabbir) December 8, 2022

Following the tweet, a friend objected that printing and displaying such photos are Ḥarām, as though the senior Muftis of Darul Uloom Deoband, including Mufti Abū al-Qāsim (b. 1366/1947) and Mufti Muḥammad Salmān Manṣūrpūrī (b. 1386/1967), who are also senior figures in Jamiat are not aware of the ruling on such photos. Whether one agrees or disagrees, the context has to be understood before passing judgement. Islam faces an existential threat in India, Muslims fear being wiped out, and to achieve this, the whole narrative and discourse pertaining to Muslims in India is being re-written. As such, it was thought necessary to use such methods to convey the role of Muslims in the liberation struggle. This, from the perspective of the management of Jamiat, was probably more important and pressing, than the need for people to have a passport that has a photograph for travels which are not mandatory in Islam. Those who study and teach in countries that do not face challenges and difficulties from the authorities would benefit a lot from travelling to countries where such challenges exist to appreciate the differing contexts.

This is indeed, the underlying lesson, of Shaykh al-Islām’s life. He did not oppose the establishment of Pakistan, because Allah forbid, he was against the implementation of Islamic laws. Rather, he was pragmatic and realistic, he felt that the Islamic system of governance which is being promised will not materialise, and millions of Muslims in the rest of India will be at greater risk. These fears of Shaykh al-Islām are being witnessed today; Pakistan is far from implementing Shariah and the Muslims of India are where they are. This is however the past which cannot be reversed. We have to look forward, and as Shaykh Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī al-Nadwī (d. 1420/1999) who foresaw the current dire state of Indian Muslims said several decades ago (p.48) said that India needs a person with the courage and zeal of Shaykh al-Islām to lead the Muslims through its challenges and to protect Islam (p.48).

We pray to Allah Almighty to illuminate the grave of Shaykh al-Islām and preserve the faith and dignity of Muslims throughout the world and unite the Ummah. Āmīn.

Yusuf Shabbir

17 Dhū al-Ḥijjah 1444 / 5 July 2023

www.islamicportal.co.uk

Book Review: 40 Hadiths on the love of the Prophet (peace be upon him)