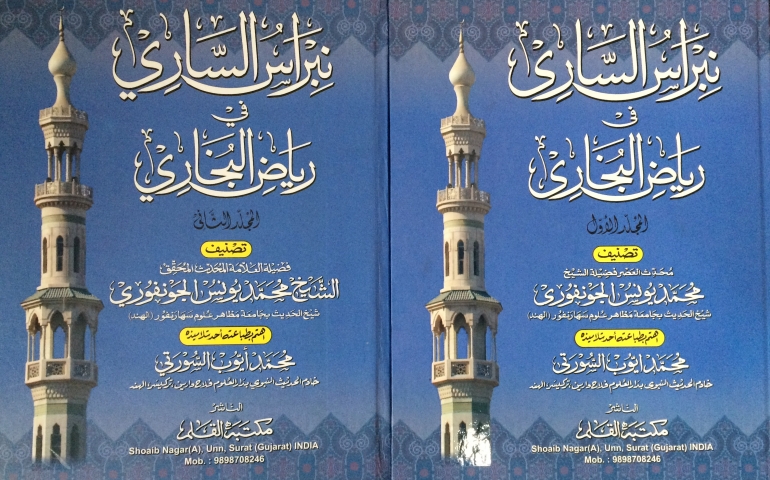

Ten salient features of the Arabic commentary Nibrās al-Sārī ilā Riyāḍ al-Bukhārī by Muḥaddith al-ʿAṣr Shaykh Muḥammad Yūnus Jownpūrī

Our respected teacher Muḥaddith al-ʿAṣr Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Muḥammad Yūnus Jownpūrī (b. 1356/1937) has dedicated his entire life to the ḥadīths of the Prophet ﷺ. He has been teaching Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī at Mazahirul Uloom Saharanpur in India for fifty years and was appointed to do so by Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Muḥammad Zakariyyā Kāndhelwī (d. 1402/1982) notwithstanding the fact that he was relatively young and there were other senior scholars alive. Mawlānā Muḥammad Zakariyyā Kāndhelwī’s confidence in his student can be further gauged by the the fact that he has quoted his student’s views in his al-Abwāb wa al-Tarājim in at least three places (1: 268, 419; 6: 788) as well as in his footnotes on Lāmiʿ al-Dirārī (10: 319), and he would regularly consult him and refer senior scholars to him particularly for ḥadīth related queries (see al-Yawāqīt al-Ghāliyah vols. 1 and 2).

Over the past fifty years, Muḥaddith al-ʿAṣr Shaykh Muḥammad Yūnus Jownpūrī has taught Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī and mastered its sciences in a manner that is unprecedented in the current era. His understanding of Imam Bukhārī and his methodology is second to none. Those who have studied with him or remained in his company attest to this. This should not come as a surprise, for he has spent his entire life in the midst of ḥadīth collections and did not involve himself in other family, social or communal matters. Despite this, his humility is such that he never intended to write a commentary on the Ṣaḥīḥ. A few years ago, at the insistence of some of his students, he agreed to collate his Arabic notes on the Ṣaḥīḥ and publish them. These notes are not mere notes. They are invaluable gems. Thus, after the hard work of some of his students and in particular our beloved Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Ayyūb Sūrtī, the first volume of the Arabic commentary by the name of Nibrās al-Sārī ilā Riyāḍ al-Bukhārī was recently published. I thought it would be useful, particularly for students, to share some salient features of this commentary. By no means is the list comprehensive or exhaustive; nor does it attempt to do justice to this invaluable book; indeed it is inconceivable for the efforts of a ḥadīth master over fifty years to be captured in a few bullet points.

(1) The commentary touches on various aspects related to the Ṣaḥīḥ with a particular and unique insight into the tarājim (chapters) of Imam Bukhārī and the profuse ocean of knowledge they contain. In this regard, this commentary is unique and offers added value; it provides an outline of the views of scholars of the past such as ʿAllāmah Ibn Baṭṭāl (d. 449/1057), ʿAllāmah Kirmānī (d. 786/1384), Ḥāfiẓ Ibn Ḥajar (d. 852/1149), Ḥāfiẓ Badr al-Dīn al-ʿAynī (d. 855/1451), Shāh Walī Allah Dehlawī (d. 1176/1762) as well scholars of the recent era such as Mawlānā Rashīd Aḥmad Gangohī (d. 1323/1905), Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Muḥammad Zakariyyā Kāndhelwī (d. 1402/1982), Shaykh al-Hind Mawlānā Maḥmūd Ḥasan Deobandī (d. 1339/1920), ʿAllāmah Anwar Shāh Kashmīrī (d. 1352/1933) and others. This is routinely followed by a critical analysis, as the author gives preference to one of the stated positions (for example, p. 329, 538) or formulates his own position, as is the case in several chapters (for example, p. 33, 133, 235, 434, 445, 551). This, as he has mentioned on several occasions, is a result of the grace of Almighty Allah who enabled Shaykh to read the text of the Ṣaḥīḥ through the lenses of Imam Bukhārī (d. 256/870) and not through the lenses of any commentator or a pre-determined jurisprudential position (see p. 475 for an example of this). Having taught Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī for several years, I can affirm that there are many chapters of the Ṣaḥīḥ where the explanation offered by our Shaykh is more often than not the most satisfactory explanation, not found in earlier commentaries. Thus, the author’s rigorous attempts to understand Imam Bukhārī deserve recognition and a particular mention.

(2) Another salient feature of the commentary is that our Shaykh does not solely rely on the famous commentaries of the Ṣaḥīḥ such as Fatḥ al-Bārī, ʿUmdat al-Qārī and others. Most commentaries published nowadays rely on a few commentaries of the Ṣahīḥ and do not go beyond. The author, however, uses a wide range of primary and secondary sources from range of disciplines including ḥadīth commentary, jurisprudence, history, language, tafsīr and others. The commentary is an encyclopedia full of references with the volume and page numbers listed from hundreds of books. I marvel at the breadth of sources used by our Shaykh at a time when there were no computers and books were not readily available. Once I heard our Shaykh say, “I read the entire Musnad ʿĀʾishah in the Musnad of Imam Aḥmad four times in pursuit of one particular word in a ḥadith.” Whilst glancing through this commentary of Shaykh, I came across the names of some books for the first time. As the compiler Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Ayyūb Sūrtī once said to me in 2010 whilst assisting him on publishing volume three of al-Yawāqīt al-Ghāliyah, “I have never heard of this book and I do not know where Shaykh got hold of such books from in the 70s and 80s.” What is interesting is that the wide range of books used by Shaykh is not restricted to the books of earlier scholars, nor is it restricted to Arabic works. For example, on page 79, Shaykh cites ʿAllāmah Ḥamīdullāh’s Khuṭubāt Bahāwalpūr in the discussion regarding Nāmūs and Nomos. Other examples of scholars of the recent past cited in this first volume include: Maḥmūd Pāshā Falakī (d. 1302/1885) (p. 92), Mawlāna Shāh Waṣī Allah (d. 1383/1964) (p. 52), Mawlānā Khalīl Aḥmad Sahāranpūrī (d. 1346/1927) (p. 429), Mawlānā Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī Nadwī (d. 1420/1999) (p. 92, 96), Shaykh al-Islām Mawlānā Ḥusayn Aḥmad Madnī (d. 1377/1957) (p. 57) and ʿAllāmah Shabbīr Aḥmad ʿUthmānī (d. 1369/1949) (p. 174, 175).

(3) The author does not rely on secondary sources and always attempts to locate the primary source. Thus, if Imam Nawawī (d. 676/1277), for example, quotes Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ (d. 544/1149) he attempts to locate the source. Likewise, if a ḥadīth has been attributed to a primary source, he leaves no stone untouched in locating the source. It is in this process that he often locates errors in attribution. For example, on page 63, he highlights an error of the author of Mishkāt al-Maṣābīḥ in attributing a ḥadīth to Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhārī. Likewise, on page 67, he critiques Ḥāfiẓ Ibn Ḥajar (d. 852/1149) for making an incomplete attribution to ʿAllāmah Ṭībī (d. 743/1342) by directly quoting from the latter’s commentary on Mishkāt al-Maṣābīḥ. Likewise, on page 153, he critiques Ḥāfiẓ Ibn Ḥajar for making an incorrect attribution to Imam Ibn Ḥazm (d. 456/1064) by quoting from the latter’s al-Muḥallā. Similarly, on page 470, he critiques Ḥāfiẓ ʿAyni (d. 855/1451) for an attribution to Imam Abū Ḥanīfah regarding the excrements of the Prophet ﷺ; Shaykh suggests he was unable to locate the attribution in any of the published books of Imam Muḥammad (d. 189/805) or the earlier Ḥanafī texts. Similarly, at one point (p. 85) Shaykh critiques a linguistic point made by ʿAllāmah Anwar Shāh Kashmīrī (d. 1352/1933) suggesting that it is not based on research and also explains the cause of the error; books were not readily available in his era. There are many more similar examples (for example, p. 229) which make this commentary extremely beneficial and highly authoritative. It is important to stress that human beings are prone to making errors, and none of us are immune, a point regularly mentioned by our Shaykh who reminds us that Ḥāfiẓ Ibn Ḥajar is our uncle and master to whom we shall remain indebted for ever. Thus, highlighting a few errors of his does not decrease his status or affect his credentials in any way.

(4) It follows on from this that this commentary is not merely a summary of previous commentaries as is the case with many commentaries. Rather, it is a critical analytical work. The author does not merely rely on the earlier works. He reviews and critiques where necessary, always with the appropriate etiquette. It is worth noting that throughout the commentary he regularly quotes his teacher Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Muḥammad Zakariyyā Kāndhelwī (d. 1402/1982) and sometimes disagrees with his analysis (for example, see p. 20 as to why Imam Bukhārī did not begin his book with Ḥamd). Anyone who has read the works of Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Muḥammad Zakariyyā Kāndhelwī can affirm that sometimes he disagrees with the ḥadīth and fiqh master Mawlānā Rashīd Aḥmad Gangohī (d. 1323/1905). Thus, capable scholars disagreeing with the views of teachers and scholars of the past is not a negative as some people with limited knowledge appear to suggest, so long as the appropriate etiquette is maintained and the disagreement has a sound basis. Throughout the book, our Shaykh quotes the views of the Sufi saints and scholars such as Shaykh ʿAbd al-Qādir Jīlānī (d. 561/1166) (p. 98) and others (p. 64, 191). However, he has no hesitation in critiquing certain extreme or erroneous Sufi positions where necessary (see for example p. 77, 247).

(5) Another salient feature of the book is that the author has used material from books that have been published recently for the first time. For example, in the commentary of Kitāb al-ʿIlm (the book of knowledge), Shaykh has cited (p. 344, 349, 372) Imam Ibn al-Sunnī’s (d. 364/975) Riyāḍat al-Mutaʿallimīn, which was published for the first time two years ago in 1436/2015.

(6) Shaykh’s attachment and connection with the Ṣaḥīḥ can be gauged by the different versions of the Ṣaḥīḥ which he not only possesses, but uses to draw critical conclusions. For example, on page 50, there is a detailed discussion regarding the first ḥadīth of the Ṣaḥīḥ and why Imam Bukhārī has only narrated the matn (text) partially, unlike the six other places in the Ṣaḥīḥ where the complete matn (text) is transmitted. Various explanations are offered in the commentary. Shaykh suggests that he has found the ḥadīth with the compelte matn (text) in the handwritten version of the Ṣaḥīḥ written by Shaykh Ismāʿīl al-Biqāʿī (d. 806/1403) (Inbāʾ, 2: 273; al-Ḍawʾ al-Lāmiʿ, 2: 303) and outlines other supporting factors for this possibility. Similarly, on page 341, Shaykh makes reference to the Sulṭāniyyah edition of the Ṣaḥīḥ.

(7) Shaykh’s style of writing is very concise and succinct. This style is also visible in his notes on the Muqaddamah of Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, published in the third volume of al-Yawāqīt al-Ghāliyah. Reading this commentary takes you on a journey to the era of Ḥāfiẓ Ibn Ḥajar and beyond. The commentary is traditional in its style and relies heavily on the earlier texts. However, the author has drawn on the writings of the recent past as mentioned already, and there are also occasions where the author has made criticism of orientalists such as Brockelmann (p. 44).

(8) Shaykh is primarily a ḥadīth expert. A few years ago in 1433/2012, Shaykh mentioned to Shaykh al-Islām Mufti Muḥammad Taqī ʿUthmānī (b. 1362/1943) that there is no book in relation to the ḥadīth and its sciences which he has not read. Thus, his insight into ʿIlal (defects), Rijāl (transmitters), Uṣūl al-Ḥadīth (principles of ḥadīth), Takhrīj, character discernment as well as the interpretation and meanings of ḥadīths is visible throughout the commentary. For example, on page 298, he agrees with Imam Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 597/1201) in relation to a ḥadīth not being established and disagrees with Ḥāfiẓ Suyūṭī (d. 911/1505) for suggesting otherwise. At another point in the book (p. 34), he suggests that there has been an omission in Tahdhīb al-Tahdhīb by the transcriber or the publisher. Similarly, on page 365, he provides the names of forty two transmitters who have transmitted a particular ḥadīth along with the references.

(9) In relation to jurisprudence, Shaykh is a follower of the Ḥanafī school of thought. However, on certain issues, Shaykh adopts the views of other schools of thought based on his research, analysis and understanding of the evidences. It is necessary on a person of such a caliber to follow his research, as I have heard Shaykh suggest on several occasions. However, this does not provide a general license for people to start formulating their own opinions as there are conditions for this set out in the books of jurisprudence. It is also worth noting that Shaykh generally errs on the side of caution when adopting a view of another school of thought and his approach is evidence based and not simply ease-based. Thus, one can expect this commentary – particularly in the later volumes – to include criticisms of the Ḥanafī evidences or positions on certain issues, just as the evidences and positions of the other schools of thought will come into the spotlight. An example of the former is on pages 265-7 where the author is inclined towards intention being necessary for all worship including ablution and critiques the Ḥanafī responses to the ḥadīth. Another example is on pages 551-3, where Shaykh outlines twelve views of the Ḥanafī school of thought in relation to an impurity falling in water and suggests that none of the positions are substantiated with sound evidences. Adopting such views does not mean that a person comes out of the fold of a school of thought as highlighted by Mawlānā ʿAbd al-Ḥayy Laknawī (d. 1304/1886), Mufti Muḥammad Taqī ʿUthmānī (b. 1362/1943) and others; both in writing and in practice. Some people assume that Shaykh’s expertise is confined to ḥadīth. A cursory glance at the commentary of Kitāb al-Wuḍūʾ disproves this. Shaykh quotes directly from the many various Ḥanafī texts from the earlier and later era. For example, in the discussion regarding Wuḍū with Nabīdh (dates water), he quotes various Ḥanafī scholars and affirms that Tayammum is to be given preference to performing ablution with Nabīdh (p. 566). Along with Imam Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan (d. 189/805), there appears to be one Ḥanafī jurist in particular who Shaykh admires and quotes regularly in this volume (p. 110, 232, 447, 568) but more so in the forthcoming volumes: Faqīh Abū al-Layth al-Samarqandī (d. 373/983). Shaykh’s approach in using primary fiqh sources is not restricted to the Ḥanafī school of thought. Rather, he uses the primary sources of all schools of thought and in this process also highlights the errors of attribution in matters of jurisprudence (for example, p. 441, 472, 568). This salient feature of Shaykh has been acknowledged by Mawlānā Salīm Allah Khan (d. 1438/2017) who suggests in Kashf al-Bārī (1:58) that he has relied on Shaykh’s durūs (lessons) in determining the jurisprudential positions of the schools of thought as well as in other ḥadīth related matters. This long awaited commentary of Shaykh explains why.

(10) Perhaps one of the most beneficial aspects of this first volume is the commentary on Kitāb al-Īmān (the book of faith). Some of the most difficult concepts and contentious issues related to Īmān (faith) and Kufr (disbelief) are presented in a concise simplified manner, drawing from the works of a broad range of scholars such as Imam Ṭaḥāwī (d. 321/933), Imam Lālkāʾī (d. 418/1027), Imam Bayhaqī (d. 458/1066), Ḥāfiẓ Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr (d. 463/1071), Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymiyah (d. 728/1328), Imam Ibn Ḥazm (d. 456/1064), Imam Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 597/1201) and others. It would be remiss of me if I did not make a particular mention of Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymiyah. Our Shaykh admires him a great deal and holds him in high regard. Like his teacher Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Mawlānā Muḥammad Zakariyyā Kāndhelwī, he describes him using lofty titles such as Shaykh al-Islām throughout his works. I have heard our Shaykh say on several occasions that he has acquired particular expertise in the science of ḥadīth from the following experts: ʿAllāmah Ibn Taymiyah (d. 728/1328), Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī (d. 748/1348), Ḥāfiẓ Ibn Kathīr (d. 774/1373), Ḥāfiẓ Ibn al-Qayyim (d. 751/1350), Ḥāfiẓ Ibn Rajab (d. 795/1393), Ḥāfiẓ Ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī (d. 744/1343), Ḥāfiẓ Zaylaʿī (d. 762/1360) and Ḥāfiz Ibn Ḥajar (d. 852/1149). Thus, throughout this commentary, there are at least twenty references and quotes from Ḥāfiẓ Ibn Taymiyah. In fact, at one juncture (p. 402), Shaykh suggests with an example, that a famous commentator of the Ṣaḥīḥ sometimes presents the research of Ḥāfiẓ Ibn Taymiyah and Ḥāfiẓ Ibn al-Qayyim without attributing it to them. I have also experienced this on a few occasions and collated some examples of this in an English article. May Allah have mercy on all these scholars to whom we shall remain indebted forever.

These are some random thoughts based on a cursory read of the book. Anyone reading this commentary will be left in no doubt that this is the most authoritative commentary of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī of the current era and the recent past. No doubt his more competent students and other readers will further highlight the salient features of this commentary and convey them more proficiently.

The first volume is 580 pages and covers the chapters of the Ṣaḥīḥ until the end of the Book of Ablution. We pray to Allah that the remaining commentary sees the light of the day and is published as soon as possible. I seek Allah’s forgiveness for my shortcomings and pray we are united in Jannah with our pious predeccessors.

Yusuf Shabbir

29 Rajab 1438 / 26 April 2017

Click on the following link for an Arabic version of the article: Ten salient features of the Arabic commentary Nibras al-Sari (Review in Arabic by Yusuf Shabbir)

Click on the following link for a detailed Urdu version of the article: Ten salient features of the Arabic commentary Nibras al-Sari (Review in Urdu by Yusuf Shabbir)

Book Review: 40 Hadiths on the love of the Prophet (peace be upon him)