In the name of Allah, the Compassionate the Merciful

Introduction

Muslims ruled Al-Andalus (the Iberian Peninsula) which includes Portugal and most of modern-day Spain for almost 800 years.

This began in 92 Hijrī (711 CE), when the Muslim Berber Commander, Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād (d. 101/720) led an army here and initiated the conquest. Within seven years, the Peninsula was conquered. There are many reasons for this swift conquest including the persecution of certain communities under the Catholic Church’s rule. Soon, Al-Andalus became a prosperous cultural and economic centre where education and the arts and sciences flourished for centuries. Its civilisation had a profound imprint across Europe and beyond. Its heartland was Andalusia in the South of the Country with Cordoba (Qurṭubah), Granada (Garnāṭah), Seville (Ishbīliyyah) and Malaga (Mālaqah) among some of its major hubs. The historian Victor Robinson wrote:

“Europe was darkened at sunset, Cordova shone with public lamps; Europe was dirty, Cordova built a thousand baths; Europe was covered with vermine, Cordova changed its undergarments daily; Europe lay in mud, Cordovas streets were paved; Europes palaces had smoke-holes in the ceiling, Cordovas arabesques were exquisite; Europes nobility could not sign its name, Cordovas children went to school; Europes monks could not read the baptismal service, Cordovas teachers created a library of Alexandrian dimensions.” (Victor Robinson, The Story of Medicine (1932), Kessinger Publishing, 2005, p.164),

Over time, the strength of the Muslims diminished, creating inroads for Christians who resented Moorish rule. The term ‘Moorish’ was used by the Christian Europeans to describe the Muslim reign here with the Muslims described as ‘Moors’. For centuries, Christian groups challenged Muslim territorial dominance here and slowly expanded their territory. This culminated in 1492, when Catholic monarchs Ferdinand II and Isabella I won the Granada War and completed the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. Most Muslims were expelled from Spain whilst many were forcefully converted to Christianity or killed.

With this history and tradition in mind, a visit to Spain was long overdue. In 2014, I had booked tickets to fly to Malaga but this did not materialise and the journey was cancelled. It was then in mid-July two weeks ago that my cousin and teacher, Mawlānā Khalīl ibn Mawlānā Hāshim mentioned to me that Ryan Air has some very cheap flights to Malaga. It was an opportunity not to be missed, so we booked the £15 return flight from Manchester to Malaga for my family (wife, two sons and daughter). My respected teacher Qārī Zakir Husen Gajaria Ṣāḥib contacted me a day or two later and also booked tickets for his family.

Day 1 – Wednesday 21 July 2021

From Manchester to Malaga

As outlined in my recent travelogues on India and Sierra Leone and The Gambia, travelling in this new world order of Covid-19 is not hassle free. Spain is currently on the amber list in the UK and does not require a PCR test for travelers who have had both their Covid-19 vaccine doses 14 days prior to travel. Children are exempt. Thus, we are saved from the hassle of the pre-travel PCR tests and also home quarantine on return, although we (adults) will have to take a PCR test in Spain and also a Day 2 test upon return (for all children aged four and above). A pre-travel declaration form is also necessary for entry into Spain, which can be completed online. Due to Brexit, Passports should also be checked to ensure they do not expire within six months.

We depart from home at 5pm with my elder sister who kindly drops us to Manchester Airport. There are very few people at the Airport. Wearing a mask is mandatory although most other Covid-19 related legal restrictions have ended in England. Qārī Ṣāḥib has already arrived with his wife Asiya Apa, three daughters, Safeeyah, Zainab, Rayhana and young son Muhammad, who recently completed the memorisation of the Quran. We check in and board the 8pm Ryan Air flight to Malaga where we arrive at midnight. Spain is an hour ahead of the UK. It is relatively quiet at Malaga Airport although it is the fourth busiest airport in Spain after Madrid–Barajas, Barcelona and Palma de Mallorca.

At Malaga Airport, we realise very quickly that English is not commonly understood in Spain which reflects the Spaniards’ pride in their own heritage, culture and language. This is something our respected Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani (b. 1362/1943) has highlighted in his travelogue ‘Andalus mey Chand Rowz’, which has also been translated into English recently entitled ‘Few days in Al-Andalus’, wherein he contrasts this with the obsession of the people of the Sub-Continent with the English language and highlights the continuation of the colonial mindset. Interestingly, a recent study suggests that almost 60% of Spanish people speak no English at all, and of the remaining, 35% do not speak it very well. What is surprising is that English is not common in the country’s tourism industry either. This reminds me of my visit to Venezuela in 2016 where like many South American countries, Spanish is prevalent and English is barely understood.

After showing our NHS vaccine certificates and pre-travel declaration forms to the airport staff, we take the taxi to the nearby Holiday Inn Express which is a few minutes away and rest for the night. Wearing a mask is necessary indoors and along with the staff, people are very particular about this.

Day 2 – Thursday 22 July 2021

From Malaga to Granada via Orgiva

Caution with Croissants and other bakery products

At breakfast, a Muslim residing at the hotel warns us that croissants and many other bakery products in Spain are not Halal, because they contain lard (pork fat). This is subsequently confirmed in several hotels during our visit although at one particular hotel, the catering manager confirms that they are Halal. Lard is commonly used in Spain so caution must be exercised.

Car Hire

After breakfast, Qārī Ṣāḥib and I return to the Airport to collect our hire cars from OK Rent a Car.

We hired two cars in advance for a week via the website www.doyouspain.com which has some excellent deals. A few tips are worth mentioning in relation to car hire:

- The earlier a car is hired, the cheaper it is. My car hire of an SUV Peugeot 3008 for the full seven days cost £210 including zero excess.

- Zero excess is recommended in foreign countries, particularly if you are not accustomated to left hand driving.

- When purchasing Zero Excess, it is advised to buy the option direct from the hire car company as part of the rental cost instead of a third-party, even if it costs a bit more. This is preferred from an Islamic perspective and also from a practical perspective, otherwise a large deposit is deducted and in the event of any damage, this is deducted by the hire company, resulting in the hassle of having to claim from the third party.

- If the arrival time is out of office hours, as was the case for us, book a hotel nearby and hire the car from the following day. This will save the hire cost of a day along with the out of hours collection and return fee.

- Choose the option of full fuel and return the car with full fuel.

Malaga (Mālaqah)

We return to the hotel, collect our families, check out and head to Malaga city.

Malaga city is capital of the Province of Malaga, in the autonomous region of Andalusia. In 2021, its population was 578,460 making it the second most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most populous in the country. It lies on the Costa del Sol (Coast of the Sun) of the Mediterranean, 62 miles east of the Strait of Gibraltar and 80 miles from North Africa. Its history spans approximately 2,800 years, making it one of the oldest cities in Europe and one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. The Encyclopaedia Britannica states:

“Málaga, port city, capital of Málaga provincia (province), in the comunidad autónoma (autonomous community) of Andalusia, southern Spain. The city lies along a wide bay of the Mediterranean Sea at the mouth of the Guadalmedina River in the centre of the Costa del Sol. It was founded by the Phoenicians in the 12th century BCE, conquered successively by the Romans and the Visigoths, and taken by the Moors in 711. Under Moorish rule, it became one of the most important cities in Andalusia. When the caliphate of Córdoba disintegrated, the kingdom of Málaga was founded, ruled over by emirs who named it “terrestrial paradise.” After they had failed several times, Christians took the city on August 19, 1487.”

The Alcazaba (Al-Qaṣabah) and Gibralfaro Castle

At 2.30pm, we arrive in the centre of Malaga city where the two monuments, the Gibralfaro Castle and the Alcazaba are located. Both are connected by a wall corridor. The archaeological remains and monuments from the Phoenician, Roman, Arabic and Christian eras are visible, making the centre of the city an ‘open museum’, displaying its history of 2,800 years.

The Alcazaba, a palatial fortification, was built by the Hammudid dynasty in the early 11th century. It is the best-preserved citadel from the Muslim era. Adjacent to the entrance of the Alcazaba are remnants of a Roman theatre dating to the 1st century BC.

The Gibralfaro Castle was built in 929 CE by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III (d. 350/961), Caliph of Cordoba, on a former Phoenician enclosure and lighthouse. Yusef 1, Sultan of Granada, enlarged it at the beginning of the 14th century, also adding the double wall down to the Alcazaba, to protect the Alcazaba. The castle is famous for its three-month siege by the Catholic monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, which ended only when hunger forced the Malagueños to surrender.

The castle is located on the top of the hill known as Mount Gibralfaro behind the Alcazaba, providing scenic views of the city and the Mediterranean Sea. We climb to the top from the side facing the Mediterranean Sea. It is also possible to drive most of the way up from the street adjacent to the exit of the monuments’ car park.

Heladería Freskitto

The temperature is 35 degrees Celsius, which means that it is time to eat some ice cream. A quick google search takes us to an ice cream shop nearby, Heladería Freskitto. The ice-cream here is worth buying.

Some scholars of Malaga

Many people have heard of the scholars of Cordoba, Seville and Granada. However, not many people know about the scholars of Malaga. A brief mention here is thus appropriate.

Many books have been authored in Arabic and other languages on the subject of the history of Spain and the Muslim scholars of the region. Specifically on Malaga, there is a 432-page book in Arabic entitled ‘Aʿlām Mālaqah’ (personalities of Malaga) authored by Qāḍī Abū ʿAbdillāh ibn ʿAskar al-Mālaqī (d. 636/1239) and completed by his nephew Abu Bakr ibn Khamīṣ. The book was published by Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmī and Dār al-Amān in 1420 Hijrī (1999 CE) and has a beneficial introduction by the researcher on the profile of the authors along with the various books authored on the subject of personalities of this region. The published version of the book is incomplete.

Some of the famous scholars of Malaga include:

- Shaykh Abū al-Muṭarrif ʿAbd al-Rahīm ibn Qāsim (d. 497/1104), who was the Mufti of Malaga and was given the title ‘Shaykh al-Mālikiyyah’ (Siyar, 19:227).

- Ḥāfiẓ Abū al-Qāsim al-Suhaylī (d. 581/1185), the famous linguist and author of the famous book al-Rawḍ al-Unuf, which is a commentary of Ibn Hishām’s (d. 218/833) al-Sīrah al-Nabawiyyah. This book of Imam Suhaylī is relied upon by the scholars of ḥadīth and history. Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī (d. 748/1348) describes him as the “scholar of Andalus” (Siyar, 21:157). Imam Suhaylī was born and grew up in Malaga city and passed away in Marrakesh (Wafayāt al-Aʿyān, 3:144). The attribution “Suhaylī” is to a village in close proximity to Malaga, which was probably his ancestral village. This village was named “Suhayl” because the Suhayl star was only visible from a mountain here. Perhaps, this is the location where later the Castillo Sohail was built by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III (d. 350/961), to strengthen the coastal defences. This is 20 miles from Malaga city. Some sources suggest that he was born in Seville (Ishbīliyyah) (Tadhkirat al-Ḥuffāẓ, 4:96), however, his birth in Malaga appears more probable considering the “al-Mālaqī” attribution after his name. This is in contrast with his teacher Qāḍī Abū Bakr ibn al-ʿArabī al-Mālikī al-Ishbīlī (d. 543/1148) who was born in Seville.

- Ḥāfiẓ Ibn al-Fakhkhār, Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm ibn Khalaf al-Mālaqī (d. 590/1194), another student of Qāḍī Abū Bakr ibn al-ʿArabī, who had memorised the entire Sunan Abī Dāwūd at a very young age and whose memorisation of Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim was renown. He was also from Malaga with his ancestral origins in Valencia. He also passed away in Marrakesh (Bugyat al-Multamis fī Tārīkh Rijāl Ahl al-Andalus, p.57; Maṭlaʿ al-Anwār, p.111; Al-Dhayl wa al-Takmilah, 4:95; Tadhkirat al-Ḥuffāz, 4:100; Siyar, 21:241).

- Ḥāfiz Ibn al-Qurṭubī, ʿAbdullāh ibn al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad al-Anṣārī al-Mālaqī (d. 611/1214), a student of the aforementioned Imam Suhaylī, and the Muḥaddīth and Khaṭīb of Malaga, whose father had migrated here from Cordoba. He passed away in Malaga (Maṭlaʿ al-Anwār, p.235; Al-Dhayl wa al-Takmilah, 2:176; Tadhkirat al-Ḥuffāẓ, 4:127; Siyar, 22:69; Al-Iḥāṭah fī Akhbār Garnāṭah, 3:309).

It is worth noting that the Arabic name of the city is spelt ‘Mālaqah’ (Muʿjam al-Buldān, 5:43; Wafayāt al-Aʿyān, 3:144), and not ‘Māliqah’ as incorrectly mentioned by Imam Samʿānī (d. 562/1166-7) in Al-Ansāb (12:46).

From Malaga to Orgiva

At 4.30pm, we depart from Malaga and travel west to Orgiva. Driving in Spain is not difficult, the roads are good. The distance between the two locations is 110km and the journey takes less than 90 minutes. The route is scenic along the coast of the Mediterranean and thereafter north along the River Guadalfeo.

We arrive Orgiva at 6pm. Orgiva is a small Spanish town in the province of Granada, Andalusia. It has a population of around 6,000 and lies in the Alpujarra valley between the Sierra de Lujar and Sierra Nevada. My maternal dear uncle, Mawlānā Muḥammad ibn Adam Patel suggested we visit this town because it is one of the few regions where Muslims remained after the fall of Al-Andalus. In addition, the three neighbouring villages Pampaneira, Bubion and Capileira are the last three villages where the Muslims held up until the very end during the final battle with the Christians.

Orgiva is a multi-cultural town and is home to several hundred Muslims. However, in the case of some, it may not be obvious that they are Muslim until they greet you with Salām.

Haqqani Zawiyah

Our first stop here is the Haqqani Zawiyah which also serves as a small mosque. The term Haqqani is an attribution to Shaykh Nāẓim Haqqānī., the controversial Sufi Shaykh who passed away in 2014. This Zawiyah is located in the outskirts of Orgiva and can only be reached via extremely narrow roads. It is not an easy place to locate.

The caretaker ʿAbd al-Raḥmān welcomes us and makes fresh lemonade for us. We also eat some fresh figs. The region is famous for its olives.

We perform Ṣalāh inside the Masjid, where we observe some drums, presumably for Dhikr. However, some locals inform us that the drums are not used.

Just before departing from here, we meet with Sheikh Omar Filipo Margarit who is the spiritual Shaykh here. We are invited to the Qur’an ḥalaqah at 9pm, however, we politely refuse due to our onward journey. The locals are welcoming.

Restaurant Teteria Baraka and Halal food in Spain

We return to Orgiva town and head to the Baraka Restaurant which serves Arab cuisine. The local staff assure us that the food is Halal and the meat is sourced from trusted local abattoirs and not imported from abroad. As a general principle, travellers should make their own enquiries and avoid relying on this travelogue. This particular restaurant nevertheless does not serve alcohol unlike most Halal restaurants we came across in Andalusia in the coming days, and in addition, the owner Brother Qasim, a Spanish revert, is active in the field of Daʿwah as I found out later. The food is good and gluten free options are also available.

The staff at the restaurant also mention that there is a local Muṣalla nearby and offer us its keys. We do not visit the Muṣalla. However, this is worth noting for those who wish to perform Ṣalāh here.

From Orgiva to Granada

We depart from Orgiva and drive to Granada city, which is a 50-minute drive.

We check into the Barcelo Granada Congress hotel at 10pm and rest for the night.

Day 3 – Friday 23 July 2021

Tour of Granada, the last city to fall

Granada (Garnāṭah)

Granada is the capital city of the province of Granada in southern Spain’s Andalusia region, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. It is known for grand examples of medieval architecture dating to the Islamic period, especially the Alhambra. This sprawling hilltop fortress complex encompasses royal palaces, serene patios, and reflecting pools from the Nasrid dynasty, as well as the fountains and orchards of the Generalife gardens. The city’s population is approximately 232,000.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica states:

“Granada, city, capital of Granada provincia (province) in the comunidad autónoma (autonomous community) of Andalusia, southern Spain. It lies along the Genil River at the north-western slope of the Sierra Nevada, 2,260 feet (689 metres) above sea level. The Darro River, much reduced by irrigation works along its lower course, flows for about a mile into the city from the east before turning sharply southward to join the Genil. It is canalized and covered along much of its course through the city. The city’s name may have been derived either from the Spanish granada (“pomegranate”), a locally abundant fruit that appears on the city’s coat of arms, or from its Moorish name, Karnattah (Gharnāṭah), possibly meaning “hill of strangers.” Granada was the site of an Iberian settlement, Elibyrge, in the 5th century BCE and of the Roman Illiberis. As the seat of the Moorish kingdom of Granada, it was the final stronghold of the Moors in Spain, falling to the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II and Isabella I in January 1492.”

It further states:

“In the northeast of the city is the Albaicín (Albayzin) quarter, the oldest section of Granada, with its narrow-cobbled streets and cármenes (Moorish-style houses). Albaicín is bounded to the south by the Darro River, and on the other side of the river is the hill upon which stands the famous Moorish palace the Alhambra, as well as the Alcazaba – the fortress that guarded it – and the Generalife, which was the summer palace of the Moorish sultans. Nearby is the 16th century palace of Emperor Charles V. Other notable Moorish antiquities are the 13th century villa known as the Cuarto Real de Santo Domingo and the Alcázar, which was built in the 14th century as a palace for Moorish queens. The Alhambra and the Generalife were collectively designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1984; the Albaicín was added in 1994.”

Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī (d. 622/1225) mentions in Muʿjam al-Buldān (4:195) that the meaning of Granada in Spanish is Pomegranate, and the city was named after it due to its beauty. As mentioned above, it was the last stronghold of Muslims in Al-Andalus and was the home of Muslim refugees fleeing from other regions during the last 250 years of Muslim rule here.

Some scholars of Granada

Some of the famous Muslim scholars of Granada include:

- Qāḍī Ibn ʿAṭiyyah, ʿAbd al-Ḥaq al-Garnāṭī, (d. 542/1148), the famous exegetist of the Qur’an whose exegesis ‘al-Muḥarrar al-Wajīz’ is published and renown. Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī describes him as ‘Imam, ʿAllāmah, Shaykh al-Mufassirīn’. He passed away in Lorca (Siyar, 19:587; Tadhkirat al-Ḥuffāẓ, 4:45, 61).

- Imam Ibn al-Faras, ʿAbd al-Munʿim ibn Muḥammad al-Anṣārī (d. 597/1201), who was an expert in the Mālikī fiqh, and was afforded the title of ‘Shaykh al-Mālikyyah’ of Granada in his era (Siyar, 21:364).

- Ḥāfiẓ Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wāḥid ibn Ibrāhīm al-Gāfiqī al-Garnāṭī al-Malāḥī (d. 619/1222), the senior ḥadīth expert and author of several works who was from a village known as Malāḥah (Tadhkirat al-Ḥuffāẓ, 4:131; Siyar, 22:162). This is today known as La Malaha, and is situated 15km from Granada city.

- Imam Abū Ḥayyān, Muḥammad ibn Yūsuf al-Garnāṭī (d. 745/1344), whose exegesis ‘al-Baḥr al-Muḥīt’ is among the renown Tafsīrs. He authored many books and eventually settled in Egypt (al-Durar al-Kāminah, 6:58). Whilst some scholars suggest he was a Shāfiʿī, it appears that he was primarily a Ẓāhirī, as outlined in my unpublished work ‘Aqwāl al-Jahābithah fī Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymiyyah’. Generally, the Mālikī fiqh remained dominant in Andalus, whilst the Ẓāhirī fiqh also made some inroads, with Imam Ibn Ḥazm al-Qurṭubī (d. 456/1064) among the leading Andalusian Ẓāhirī scholars.

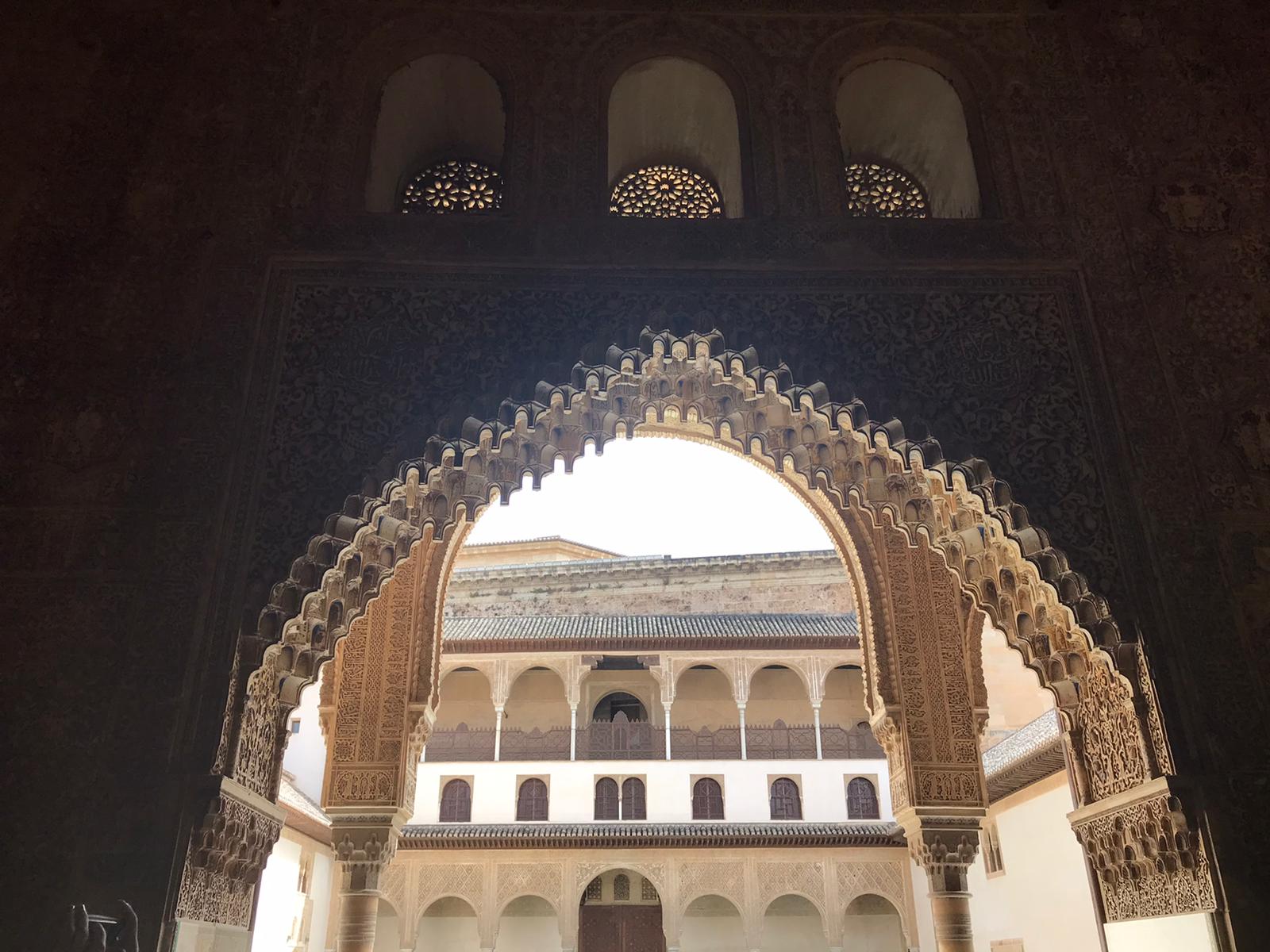

Alhambra

The most prominent and breath-taking attraction of Granada city is the Alhambra (Al-Ḥamrāʾ), which translates as the red (castle/palace), either because of the reddish walls and towers that surrounded the citadel, or because it was built between 1238 and 1358, in the reigns of Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Nasr (d. 671/1273), also known as Ibn al-Aḥmar due to his reddish hair. He was the founder of the Nasrid dynasty (1232-1492) which was the last Muslim dynasty to rule Al-Andalus.

The Alhambra is the most important surviving remnant of the period of Islamic rule in Al-Andalus. It was inscribed on the World Heritage list in 1984 due to its universal beauty and exceptional expression of Moorish and Andalusian culture as well as its ability to convey the history of the changes to the region over time through its architecture and decor. The plateau upon which it was built overlooks the Albaicín (Albayzin) quarter of Granada’s Moorish old city. At the base of the plateau, the Darro River flows through a deep ravine on the north.

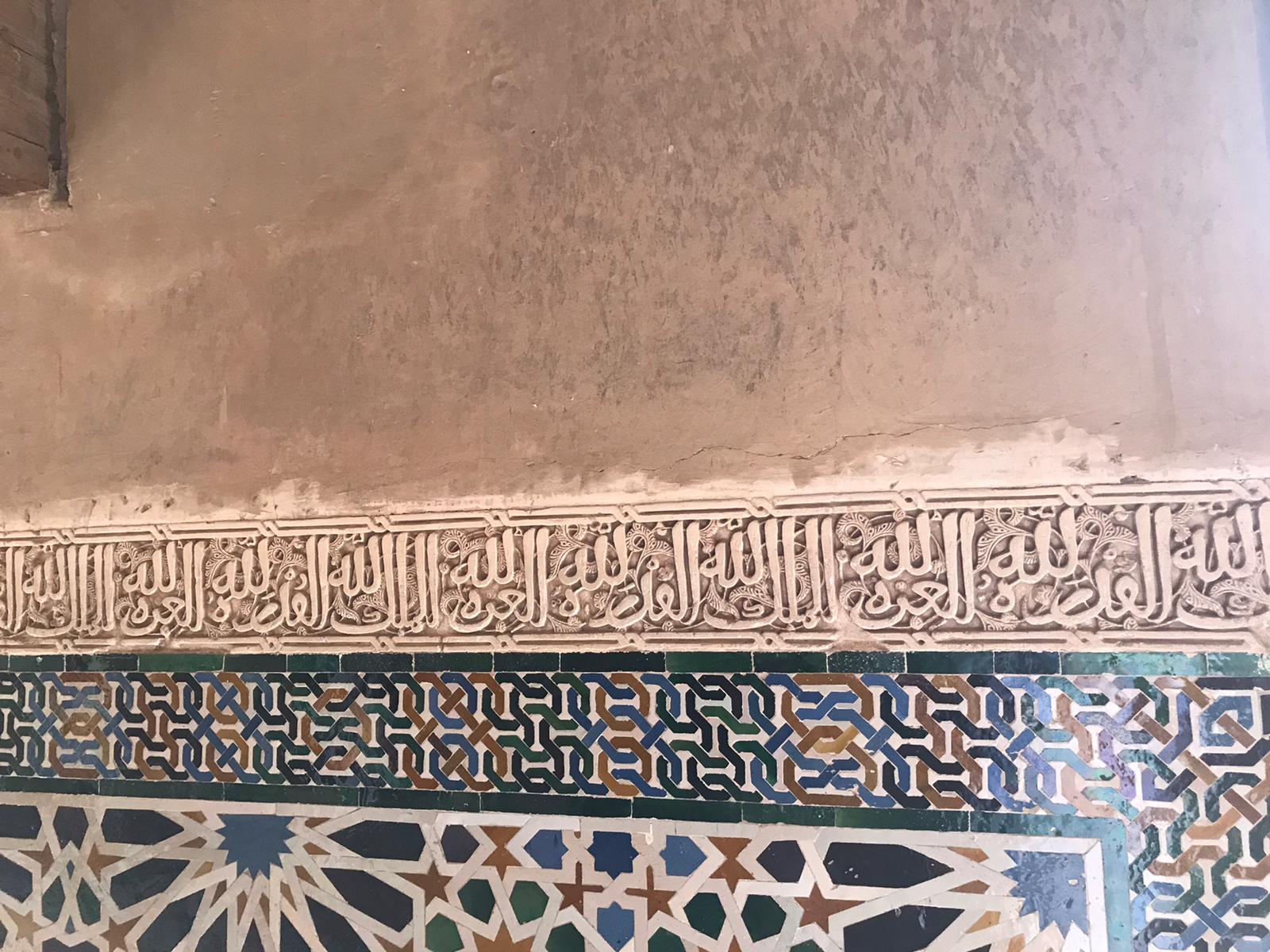

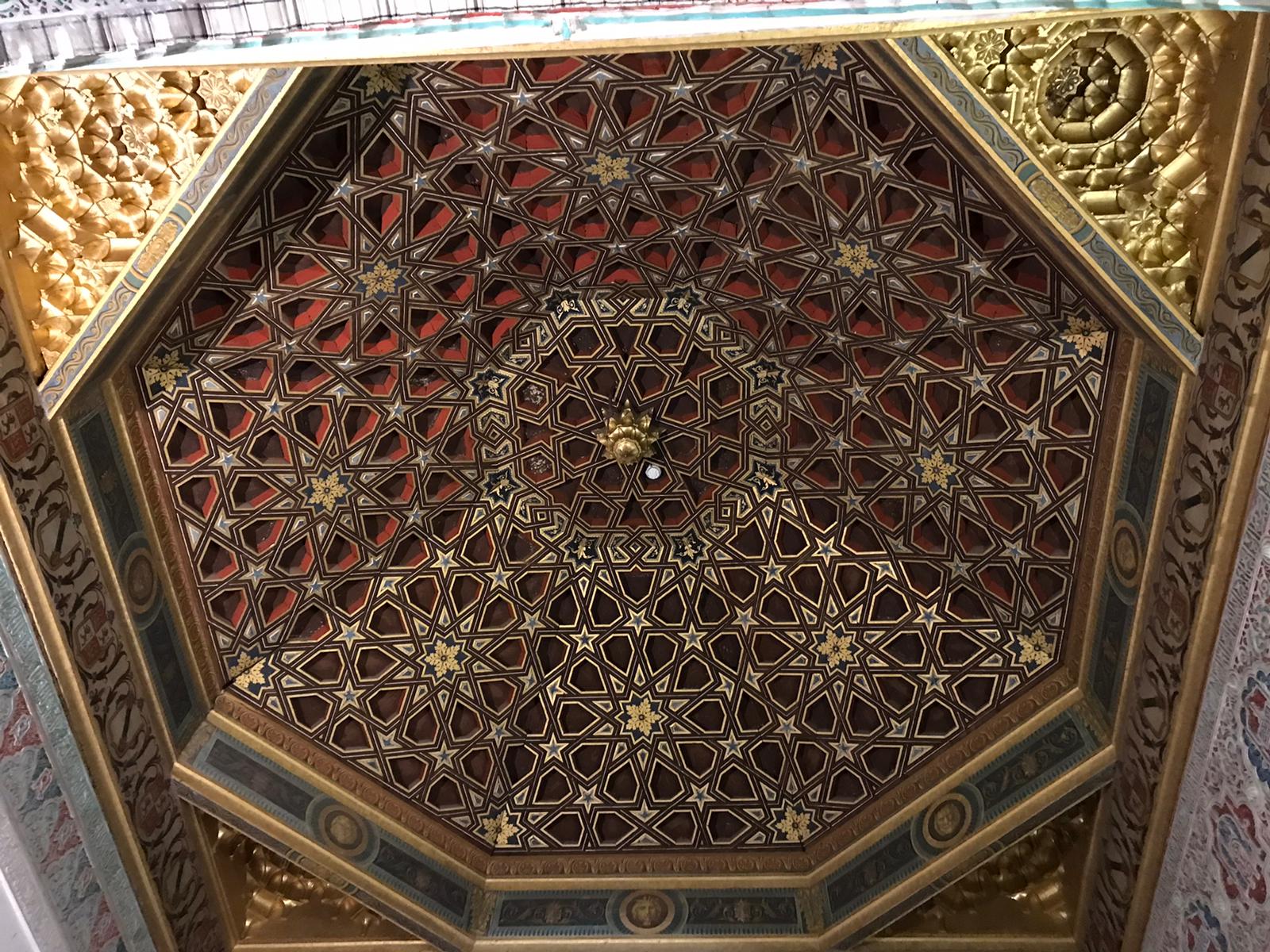

The Alhambra is not just a Palace. It is a castle and a fortress, a royal palace and a town, amazing gardens and a summer retreat. In fact, in its heyday, it was a mini-city separate from the town beneath it. It contained mosques, schools, shops, poor and wealthy quarters, public baths, prisons, barracks, administrative buildings, a royal cemetery, and a mint. Central to the Alhambra complex is the Nasrid Palaces, mostly built in the 14th century. It is a labyrinthine complex, and a sumptuous display of Muslim architecture, with marble floors, colourful azulejos (tiles), arabesque stuccowork, artesonado (elaborately patterned recessed wood) ceilings, muqarnas (hanging honeycomb forms, often compared to stalactites), and beautiful, cursive Arabic calligraphy. There are also gardens, bushes and trees, and an abundance of water in pools or flowing from fountains.

Visit to Alhambra

After breakfast, we take the taxi to the Alhambra. Private cars are not permitted to drive around the Alhambra during the day until 10pm. We arrive at the main entrance of the Alhambra at midday.

We had purchased tickets in advance via https://tickets.alhambra-patronato.es/en/, this is strongly recommended especially during busy seasons. When booking tickets, it is necessary to select a date and also a specific time on that date to visit the Nasrid Palaces. The date and time are not changeable. We had booked 4pm for the Nasrid Palaces assuming that Jumuʿah Ṣalāh will take place at 1.30pm or 2pm. However, we were informed thereafter that Jumuʿah Ṣalāh is at 3pm at a local mosque. We attempted to change the time due to this, however, this was not possible.

As we enter the Alhambra, many guides offer their services to us. They are expensive. Shaykh Muhammad Idreesi (see Seville below for his profile) had suggested we book a Muslim guide and recommended some names. We did not think much of this. However, this would have been worthwhile. We opted for an audio guide which does not cost much.

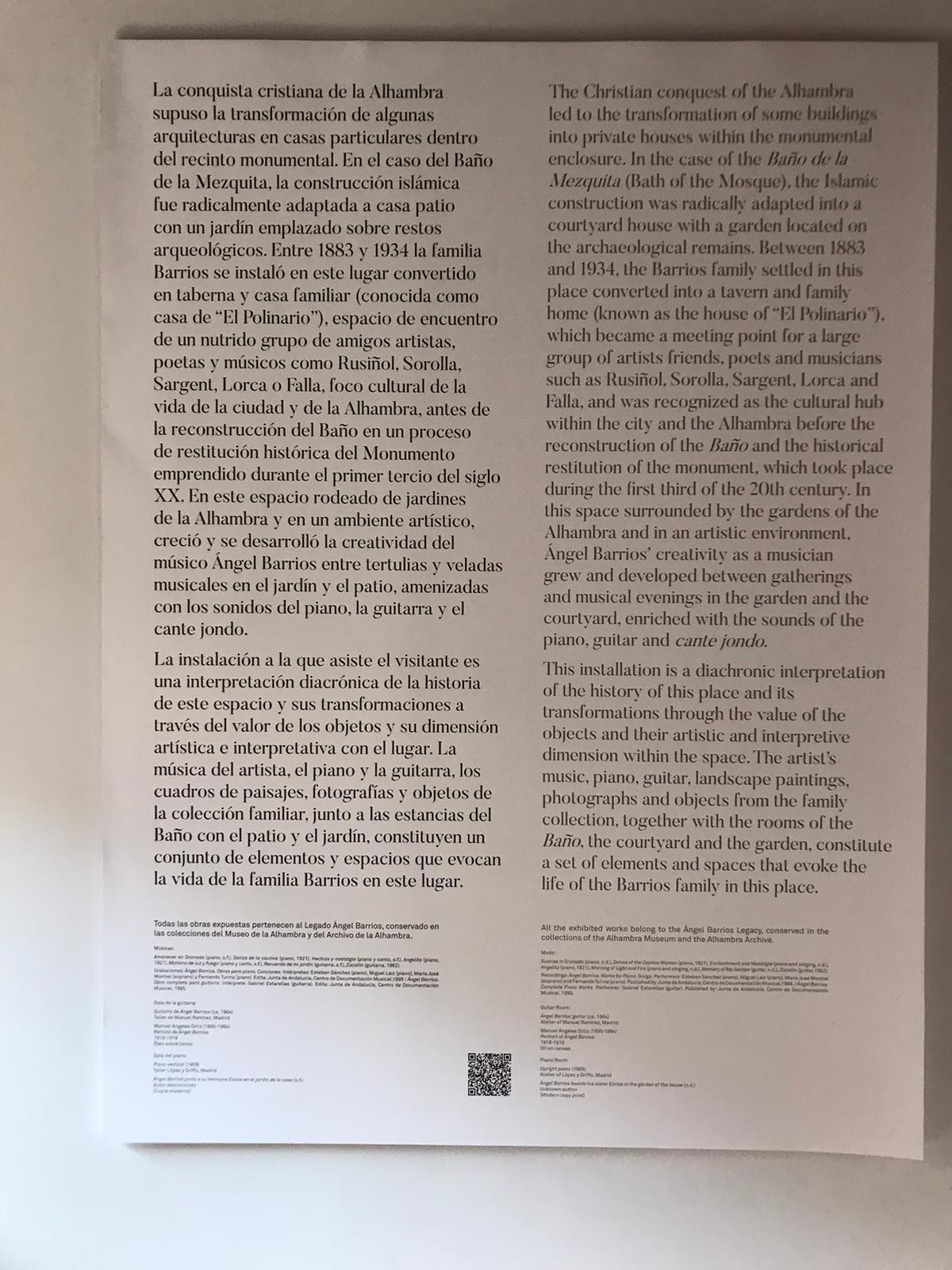

We visit various parts of the Alhambra including Generalife and the historic buildings between the Generalife and Alcazaba including the Palacio De Los Abencerrajes (Abencerrajes Palace), the Bano De La Mezquita (Bath of the Mosque), the Church of Santa María de la which was built on the site of Alhambra’s great mosque, and finally the Alcazaba fortress.

Granada is much warmer than Malaga with the temperature reaching 40 degrees Celsius today. This poses a challenge with young children, and in light of our experience, it would be better to visit the Nasrid Palaces first, to get the most important visit out of the way.

Masjid Garnatah al-Jami – Mezquita Mayor de Granada

At 2.45pm, we leave from the taxi stand close to the Nasrid Palaces and head to Masjid Garnatah al-Jami known as Mezquita Mayor de Granada. The short trip takes you through the narrow streets of the Albaicin, providing a glimpse into this historic Muslim quarter.

We arrive shortly after 3pm, and realise that Jumuʿah Ṣalāh was in fact 2.30pm. We perform Ẓuhr Ṣalāh in the small Masjid which is situated on a hill with a splendid garden offering beautiful views of the Alhambra opposite.

There is also a Halal food outlet outside the Masjid. Some locals inform us that many local Spaniards are reverting to Islam.

It is worth noting that this Masjid was established by the Scottish revert, Abdalqadir as-Sufi (born Ian Dallas), a Shaykh of the Darqawi-Shadhili-Qadiri Tariqa, founder of the Murabitun World Movement and author of numerous books. He was born in Scotland and was an actor before he converted to Islam in 1967. Sadly, a week after our visit, he passed away on 1st August 2021 in Cape Town, South Africa, where he established the Jumu’a Mosque.

There is also another mosque in the city, Masjid Al-Taqwa (Mezquita At-Taqwa), near the Granada Cathedral.

Nasrid Palaces

We return to the Nasrid Palaces by 4pm, our scheduled time.

While all of the Alhambra is fascinating, the Nasrid Palaces are what really makes it worth visiting. As the Huma’s Travel Guide to Islamic Spain notes:

“With their breath-taking decorations, shady arcades and tranquil patios, the visitor is propelled into a different world where Muslim sovereigns lived, ruled and entertained dignitaries. The palaces, patios and gardens were designed to remind the viewer of Paradise, in the interweaving of water channels and pools into the built environment, the representations of heaven in the star-strewn geometric cupolas, and the Qur’anic inscriptions which make up 10% of the 10,000 or so Arabic inscriptions on the palace walls. Although the complex is very, well, complex, there are three main areas that served as the royal palace, each with its own palace, portico and patio: the Mexuar, where justice was imparted to the citizens of Granada; the Torre de Comares, where court was held; and the Palacio de los Leones, the Harem or family residence.”

Undoubtedly, The Nasrid Palaces within the Alhambra feature some breath-taking views.

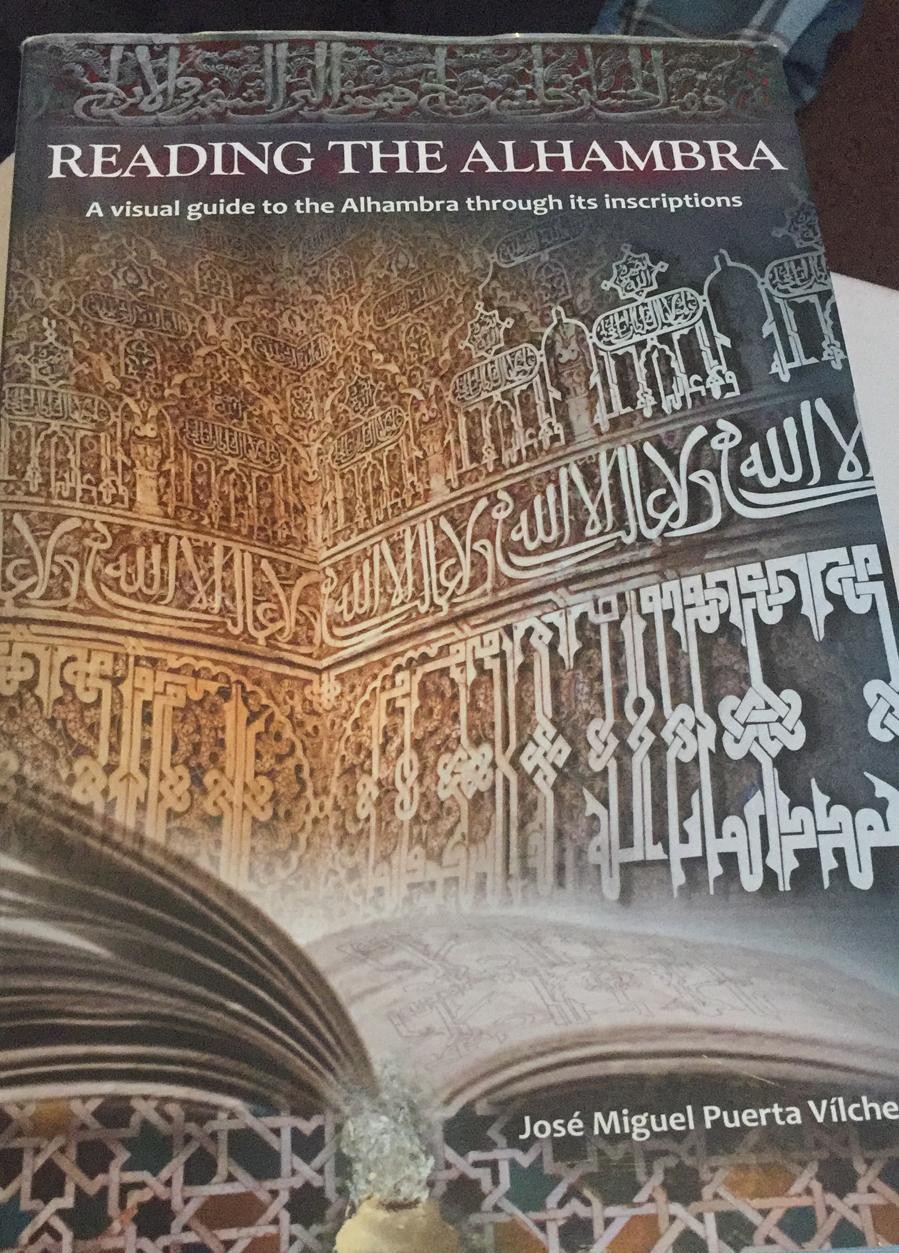

The most prominent and often repeated inscription on the walls states “Wa-la Ghalib illa Allah” (There is no Victor but Allah). In this specific context of the inscriptions, there is a book in English by Professor José Miguel Puerta Vílchez entitled ‘Reading the Alhambra – A visual guide to the Alhambra through its inscriptions.’

A practical tip for those with young children or elderly people is that if you wish to suffice on the visit to the Nasrid Palaces, you can take the Taxi to the stand near the Nasrid Palaces, as opposed to the main entrance of the Alhambra. The Alcazaba fortress is very close to the Nasrid Palaces, so this can also be visited, to view the entire city.

Halal Food Places

We leave the Alhambra at 5.30pm and head to ‘Elvira’ road, where there are several Halal restaurants and take-aways. Again, the locals insist that the meat is Halal, sourced from local Spanish abattoirs. Almost all the restaurants here serve alcohol.

Other attractions in Granada

We had planned to visit several other attractions today, however, we returned to the hotel as the children were tired. They are:

- Hammam Al Andalus

- Madraza (Madrasa Yusufiyyah), the last Madrasah of Islamic Spain. At the time, it stood directly opposite the Jame Mosque, which was destroyed and rebuilt as a cathedral.

- Zoco/Souk – the traditional market.

All three are located in close proximity to each other, within a short walking distance from the food places mentioned above. When arriving in Granada, and likewise Cordoba and Seville, it is useful to obtain a map of the city from the hotel staff to plan the visit in an orderly manner.

Lidl

In the evening, we visit a local Lidl superstore and purchase snacks and water bottles. There are many Lidl and Aldi superstores across Spain. This is particularly useful because prices in tourist areas are very expensive. In addition, if the holiday flight does not allow luggage, there is no need to pay extra.

Day 4 – Saturday 24 July 2021

Cordoba, where the heart bleeds

Barcelo Granada Congress hotel, Granada

Yesterday morning, the hotel staff confirmed to us that the croissants and some other bakery products are not Halal. Although this hotel is rated four star, its service and the breakfast are undoubtedly five star. Of particular mention is the fresh orange juice and the Churros which has its origins in Spain. The swimming pool on the hotel roof is not as large as we assumed. Hotels in Spain charge for car parking, however, the hotel reduces the price for us from 18 euros to 9 euros per night per vehicle.

From Granada to Cordoba

We depart from Granada at 1pm for Cordoba. There are several routes to Cordoba. We travel on the fastest route which takes us west on the A-92 towards Loja (لوشة) and Antequera (أنتقير، الأنتكيرة) and thereafter north on the A-45 via Lucena (ليسانة، أليسانة). The distance between the two cities on this route is 200km.

Loja is where the famous poet, writer, historian, philosopher, physician and politician, Lisān al-Dīn Ibn al-Khaṭīb (d. 776/1374) was born. Among his famous works is: ‘al-Iḥāṭah fī Akhbār Garnāṭah’ (الإحاطة في أخبار غرناطة).

Lucena was a Jewish town. This is where the famous philosopher and Mālikī jurist, Imam Ibn Rushd al-Qurṭubī (d. 595/1198) who is known as Averroes was exiled for some time.

Another route from Granada to Cordoba is via Jaen (جيَّان). A famous scholar of Jaen is the Muḥaddith of Andalus, the great Ḥadīth expert, Ḥāfiẓ Abū ʿAlī al-Gassānī al-Jayyānī (d. 498/1105), the author of ‘Taqyīd al-Muhmal wa Tamyīz al-Mushkil’, an authoritative book on the transmitters of ḥadīths in Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhārī and Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim. Interestingly, he never left Andalus (Siyar, 19:148; Tadhkirat al-Ḥuffāẓ, 4:22). Another famous scholar of Jaen is ʿAllāmah Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAbdullah al-Jayyānī (d. 563/1168) who was advised by the Prophetﷺ in a dream to avoid polemics and instead occupy himself with ḥadīths (Siyar, 20:509).

There is also a shorter route between Granada and Cordoba, via the N-432 local road. The distance on this route is 163km.

Cordoba (Qurṭubah)

We arrive Cordoba after 3pm. The city appears less developed than Malaga and Granada although it does have an airport. It is the capital of the province of Cordoba and is the third most populated municipality in Andalusia, after Sevilla and Malaga. Its population in 2018 was 325,708.

The Encyclopedia Britannica provides a useful overview of the history of the city:

“Córdoba, conventional Cordova, city, capital of Córdoba provincia (province), in the north-central section of the comunidad autónoma (autonomous community) of Andalusia in southern Spain. It lies at the southern foot of the Morena Mountains and on the right (north) bank of the Guadalquivir River, about 80 miles (130 km) northeast of Sevilla. Córdoba was probably Carthaginian in origin and was occupied by the Romans in 152 BC.”

“The city flourished under their rule, though 20,000 of its inhabitants were massacred in 45 BC by Julius Caesar for having supported the sons of Pompey. Under Augustus, the city became the capital of the prosperous Roman province of Baetica. It declined under the rule of the Visigoths from the 6th to the early 8th century AD.”

“In 711 Córdoba was captured and largely destroyed by the Muslims. Its recovery was impeded by tribal rivalries until ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I, a member of the Umayyad family, accepted the leadership of the Spanish Muslims and made Córdoba his capital in 756. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I founded the Great Mosque of Córdoba, which was enlarged by his successors and completed about 976 by Abū ʿĀmir al-Manṣūr. Though troubled by occasional revolt, Córdoba grew rapidly under Umayyad rule; and after ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III proclaimed himself caliph of the West in 929, it became the largest and probably the most cultured city in Europe, with a population of some 100,000 in 1000. Under Umayyad rule, Córdoba was enlarged and filled with palaces and mosques. The city’s woven silks and elaborate brocades, leatherwork, and jewelry were prized throughout Europe and the East, and its copyists rivaled Christian monks in the production of religious works. When the caliphate was dismembered by civil war early in the 11th century, Córdoba became the centre of a contest for power among the petty Muslim kingdoms of Spain. It fell to the Castilian king Ferdinand III in 1236 and became part of Christian Spain.”

It further states:

“Córdoba remains a typically Moorish city with narrow, winding streets, especially in the older quarter of the centre and, farther west, the Judería (Jewish quarter). A Moorish bridge with 16 arches on Roman bases connects Córdoba with its suburbs across the river. The bridge is guarded at its southern end by the Calahorra fortress. West of the bridge, near the river, lies the Alcázar, or palace, which was the residence of the caliphs and is now in ruins. Other important buildings include several old monasteries and churches, the city hall, various schools and colleges, and museums of fine arts and archaeology. Córdoba’s Moorish character and its fine buildings—especially the Great Mosque—have made it a popular tourist attraction.”

Eurostars Palace Hotel

We check into the five-star Eurostars Palace Hotel, on Paseo de la Victoria, which is ideally located at the pivot point between modern Cordoba and the old city centre. Book a junior suite with views of the old city including the Great Mosque and enjoy the stay here.

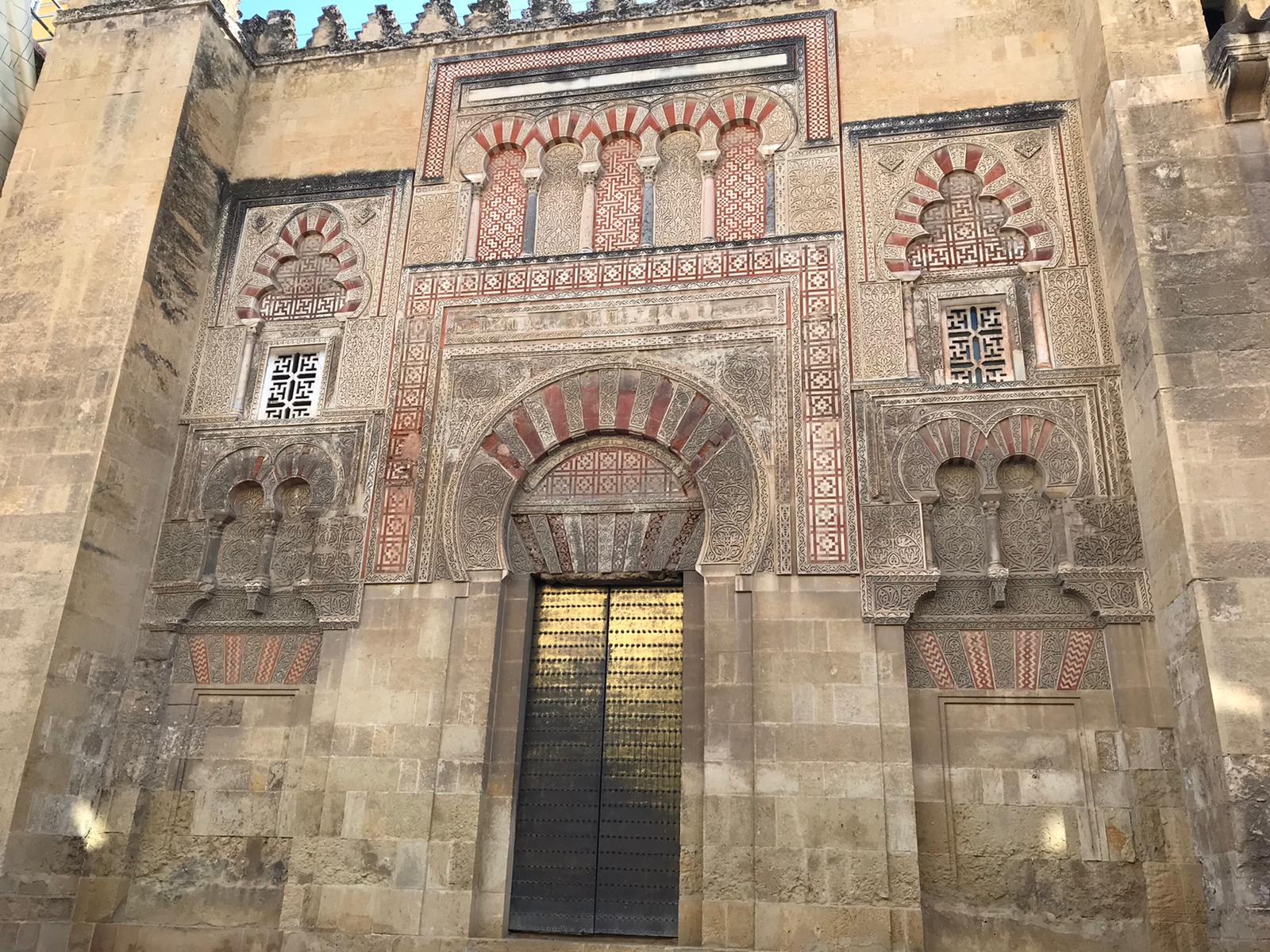

The Great Mosque of Cordoba (Jāmiʿ Qurṭubah)

There are many attractions in Cordoba. However, the most important is the Great Mosque. The hotel staff inform us that it closes at 7pm. We therefore walk to the Mosque, purchase tickets (11 euros for adults, free for children) and enter. The Masjid can only be truly appreciated after visiting it. It is one of the world’s most impressive buildings, making it one of the most remarkable tourist attractions in Spain.

Later in the evening, I post the following on Facebook:

“The heart bleeds when you visit the Masjid in Cordoba (Qurṭubah) which was converted to a church in the 13th century. It was probably the largest Masjid building at the time across the world. The building has mammoth dimensions: It stretches across 24,000 square meters and features as many as 856 aesthetic columns made of marble, granite, jasper and other fine materials. This was the hub of Islamic learning and civilisation in general. Great scholars such as Ibn Ḥazm, Ibn Rushd, Abu al-ʿAbbās al-Qurṭubī, Abū ʿAbdullāh al-Qurṭubī lived and taught here, whose books feature on the shelves of Islamic libraries worldwide. A 1000 years ago, Cordoba was the most spectacular city in Europe. It boasted paved and well-lit streets, running water, thousands of shops and libraries, including the caliph’s library, which held some 400,000 books. However, today we were unable to perform two Rakʿat Ṣalāh here in this Masjid. Security officers followed us around. The most we (my respected teacher Qari Zakir Sahib and I) could do was perform Ṣalāh on a chair by Ishārah (gestures). The Masjid is filled with Christian imagery. How humiliating for the Ummah of over a billion. May Allah unite us and revert this region and other parts of the Muslim world to a glorious united Muslim rule.”

I also posted the following couplets from the Nūniyyah of the Andalusian poet, Abū al-Baqā al-Rundi (d. 684/1285), in which he documents the exile of the Muslims and the state of the Masjids:

حيث المساجد قد صارت كنائس ما

فيهن إلا نواقيس وصلبان حتى

المحاريب تبكي وهي جامدة

حتى المنابر ترثي وهي عيدان

Where Masjids have become churches

Where only bells and crosses are found

Even the mihrabs weep

Though they are solid

Even the pulpits mourn

Though they are of wood

This remains true to date. Much has been written about the reasons for the fall of Spain. One fundamental reason and cause is division and friction within the Muslims. ʿAllāmah Abū al-ʿAbbās al-Qurṭubī (d. 656/1258) writes, “When the rulers of the Maghreb fought and argued with each other, the Firanj (Franks/Europeans) took over all the cities of Al-Andalus” (al-Mufhim, 7:218). Thus, the message from the Masjid is loud and clear – unite yourselves, otherwise your fate will be like mine.

Some scholars of Cordoba

As we tour the Masjid, we think to ourselves that this was the place where once upon a time, great scholars delivered their lessons and authored books. It is beyond the scope of this travelogue to list the famous scholars of Cordoba. Nevertheless, a few are mentioned by way of example:

- ʿAllāmah Ibn Ḥazm (d. 456/1064), the famous Ẓāhirī jurist and ḥadīth expert and author of many works including his infamous ‘al-Muḥallā’ was born in Cordoba. He was renowned for his attacks on other schools of jurisprudence and in this regard held public debates with ʿAllāmah Abū al-Walīd al-Bājī al-Mālikī (d. 474/1081) who was from Beja (Bājah). He eventually moved to Manta Lisham in Lablah (Neibla) and spent the final years of his life there. Despite his style, Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī comments that his critic the great Imam Abū Bakr ibn al-ʿArabī al-Ishbīlī al-Mālikī (d. 543/1148) did not reach his status. The great Shāfiʿī scholar, ʿIzz al-Dīn ibn ʿAbd al-Salām (d. 660/1262), who was known as the Sulṭān of scholars said, “I have not seen among the Islamic books on knowledge anything like al-Muḥallā of Ibn Ḥazm and al-Mugnī of Shaykh Muwaffaq al-Dīn (Ibn Qudāmah al-Ḥanbalī).” Ḥāfiz Dhahabī adds to this al-Sunan al-Kubrā of Imam Bayhaqī (d. 458/1066) and al-Tamhīd of Ḥāfiẓ Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr (d. 463/1071) (Siyar, 18:184; 20:202). What is remarkable about ʿAllāmah Ibn Ḥazm is that he authored a book ‘Ḥajjat al-Wadāʿ’ which is relied upon by scholars after him, despite the fact that he never performed Hajj (Zād al-Maʿād, 2:213).

- Shaykh al-Islam Ḥāfiẓ Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr (d. 463/1071), the great Mālikī ḥadīth scholar whose books al-Tamhīd, al-Istidhkār, al-Istīʿāb, Jāmiʿ Bayān al-ʿIlm wa Faḍlih and others are universally accepted and relied upon books. His students include the aforementioned Imam Ibn Ḥazm as well as Ḥāfiẓ Abū ʿAlī al-Gassānī. He was born in Cordoba and passed away in Shāṭibah (Jativa) (Siyar, 18:153).

- The Mālikī judge based in Cordoba, ʿAllāmah Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Khalf al-Tujībī, known as Ibn al-Ḥāj (d. 529/1134), who was an expert in the ḥadīth sciences as well as legal verdicts. He was patient, forbearing and humble. His students include ʿAllāmah Ibn Bashkuwāl al-Qurṭubī (d. 578/1183), the author of many books, who was also born in Cordoba. ʿAllāmah Ibn al-Ḥāj was killed in the Great Masjid of Cordoba whilst performing Jumuʿah Ṣalāh in the state of Sajdah at the age of 71 (al-Ṣilah, p.550; Siyar, 19:614; al-Aʿlām, 5:317). It is for this reason, he is included in the following article on the pious luminaries who passed away in Sajdah https://islamicportal.co.uk/forty-pious-people-who-passed-away-in-sajdah/. It should be noted that this is not ʿAllāmah Ibn al-Ḥāj al-Mālikī (d. 737/1336), the famous author of al-Madkhal.

- Imam Ibn Rushd (d. 595/1198), whose name is often latinized as Averroes, a Mālikī jurist and intellectual, who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, mathematics, Islamic jurisprudence and law, and linguistics. He is known as the father of rationalism. He was born in Cordoba and passed away in Marrakesh. His famous work in Islamic jurisprudence is ‘Bidāyat al-Mujtahid’ (Siyar, 21:307).

- ʿAllāmah Abū al-ʿAbbās al-Qurṭubī (d. 656/1258), the author of ‘Al-Mufhim’, the commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim which is fully published. When the term ‘al-Qurṭubī’ is mentioned on its own in ḥadīth commentaries, it generally refers to him. Sometimes it refers to ʿAllāmah Abū ʿAbd Allah al-Qurṭubī particularly when matters pertaining to the hereafter are cited from his ‘Al-Tadhkirah bi Aḥwāl al-Mawtā wa Umūr al-Ākhirah’. ʿAllāmah Abū al-ʿAbbās al-Qurṭubī was born in Cordoba and passed away in Alexandria, Egypt. Interestingly, he mentions in al-Mufhim (5:22) that rape and other indecent actions increased in Al-Andalus among Muslims which resulted in Allah enabling the enemy to overpower them. He also mentions (5:439) that it was common in Al-Andalus for Taḥnīk to be done on the seventh day with raisins and figs.

- ʿAllāmah Abū ʿAbd Allah al-Qurṭubī (d. 671/1273), whose exegesis of the Quran is among the most famous tafsīr books. When ‘al-Qurṭubī’ is mentioned on its own in tafsīr books, it refers to him. He grew up in Cordoba and after its capture in 633/1236 by Ferdinand III, he moved to Egypt and passed away there. In 1971, his body was exhumed and reburied under a mausoleum in his name which is open to visitors.

Some of the famous scientists of Cordoba include:

- ʿAbbās ibn Firnās (d. 274/887), the first man to fly and thereby the father of aviation. He was born in Ronda and lived and died in Cordoba.

- Abū al-Qāsim al-Zahrāwī (d. ca. 404/1013), who is considered to be the greatest surgeon of the Middle Ages and has been referred to as ‘the father of modern surgery’. He was born in Madinat al-Zahra near Cordoba and passed away in Cordoba.

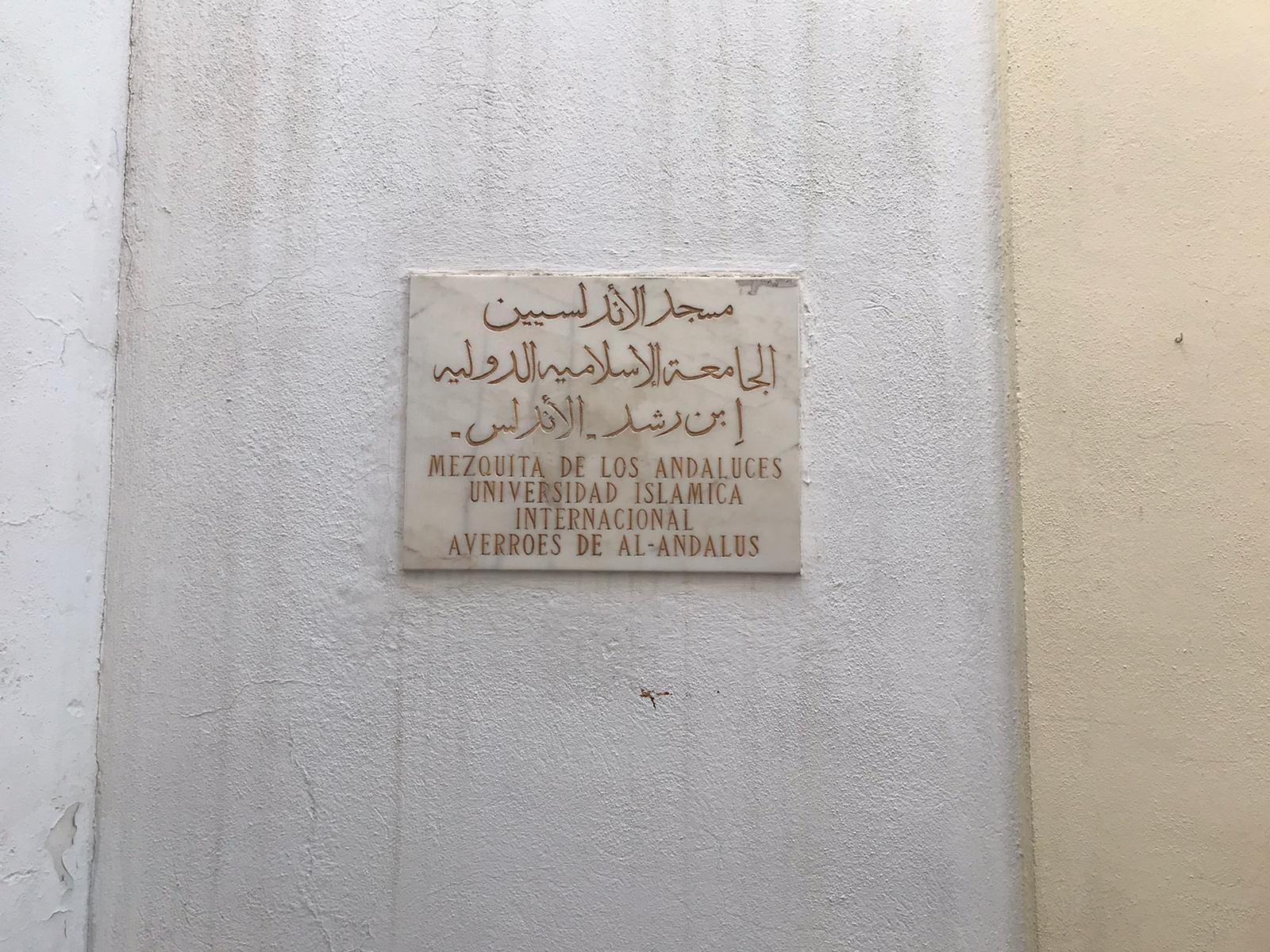

Masjid al-Andalusiyyīn (Mezquita de los Andaluces)

As we exit the Great Mosque of Cordoba, we enquire about a Masjid where we can perform Ṣalāh. We are directed to a small Masjid located in a narrow alley behind the Great Mosque. Qārī Ṣāḥib’s wife Asiya Apa comments that this Masjid is smaller than the Stansfield Street Mosque in Blackburn which is based in a terraced house.

We perform Ṣalāh at this Masjid, eat dinner in the neighbouring Teteria Petra restaurant which serves Arabic cuisine, and return to our hotel. There are some beautiful ponds outside the walls of the old city.

Qiblah of the Great Mosque of Cordoba

Later in the evening, as I try to work out the Qiblah from our hotel, I feel that either my mobile compass is wrong or the Qiblah of the Great Mosque of Cordoba is wrong. In Granada, I had used 100 degrees from the North as the Qiblah direction and when I apply the same in Cordoba, there appears to be a big variance with the Qiblah of the Masjid which is visible from my hotel room window. After performing Ṣalāh, a cursory search on the internet suggests that there is indeed an issue and that the Qiblah of the Great Mosque is facing the deserts of Algeria and not Saudi Arabia. It is 150 degrees from North, when it should be 100 degrees.

One explanation behind this is that the early Muslims applied the Qiblah direction of Damascus given that it was the capital of the Umayyads. The Qiblah direction from Damascus is 164 degrees, however, the prevalent Qiblah there at the time was 150 degrees. This is perhaps the most plausible explanation although David A. King rejects this in his article, ‘The enigmatic orientation of the Great Mosque of Córdoba’ suggesting that it is pure coincidence (p.41). Perhaps, the earlier Muslims applied the ḥadīth “What is between the east and west is a qiblah” (Sunan al-Tirmidhī, 342) to deduce southern alignments more broadly although the ḥadīth was specifically for the blessed city of Madīnah.

David A. King suggests that both the Mosque and the Kaʿbah are aligned in the same direction via astronomical horizon phenomena. In simple terms, the different sides of the Kaʿbah are associated with different parts of the Muslim world, the northwest face of the Kaʿbah was associated with Al-Andalus and, accordingly, the Great Mosque of Cordoba was oriented towards the southeast as if facing the Kaʿbah’s north-western facade, with its main axis parallel to the main axis of the Kaʿbah structure.

This, however, does not appear plausible. David A. King quotes (p. 58) earlier scholars who mention that during the Islamic rule, there were attempts to correct the Qiblah of the Great Mosque as it was strongly deviated towards the west. However, the Qiblah was not modified due to opposition based on the practice of the predecessors, without any reference to an alternative method of determining the Qiblah.

Another reason why King’s theory is not plausible is because later mosques in Al-Andalus had more eastern-facing orientations, for example, the Mosque of Madinat al-Zahra built in the 10th century. Another reason is that I am not aware of any jurists who have permitted determining Qiblah in the way described by King.

I have not had the chance to investigate the matter further, the issue requires more research. And Allah Almighty knows best regarding the basis of this Qiblah direction and why it was not corrected in subsequent centuries.

Day 5 – Sunday 25 July 2021

Visit to Madinat al-Zahra

Madinat al-Zahra

After breakfast at the hotel, we start the day by visiting the historic Madinat al-Zahra, a fortified palace city, which is a few kilometers from Cordoba city. We travel by car; it is also possible to travel by coach from opposite our hotel. The city was built by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III (d. 350/961), the 1st caliph of Al-Andalus, and it served as the capital of the Caliphate of Cordoba. The UNESCO website states:

“The Caliphate city of Medina Azahara is an archaeological site of a city built in the mid-10th century CE by the Umayyad dynasty as the seat of the Caliphate of Cordoba. After prospering for several years, it was laid to waste during the civil war that put an end to the Caliphate in 1009-1010. The remains of the city were forgotten for almost 1,000 years until their rediscovery in the early 20th century. This complete urban ensemble features infrastructure such as roads, bridges, water systems, buildings, decorative elements and everyday objects. It provides in-depth knowledge of the now vanished Western Islamic civilization of Al-Andalus, at the height of its splendour.”

We arrive at the car park and ride on the official bus to the city. There is no entrance fee for EU citizens including British people. However, there is a nominal cost for the bus ride. We arrive at the site and walk through the remains of the city, which is now a major archaeological site.

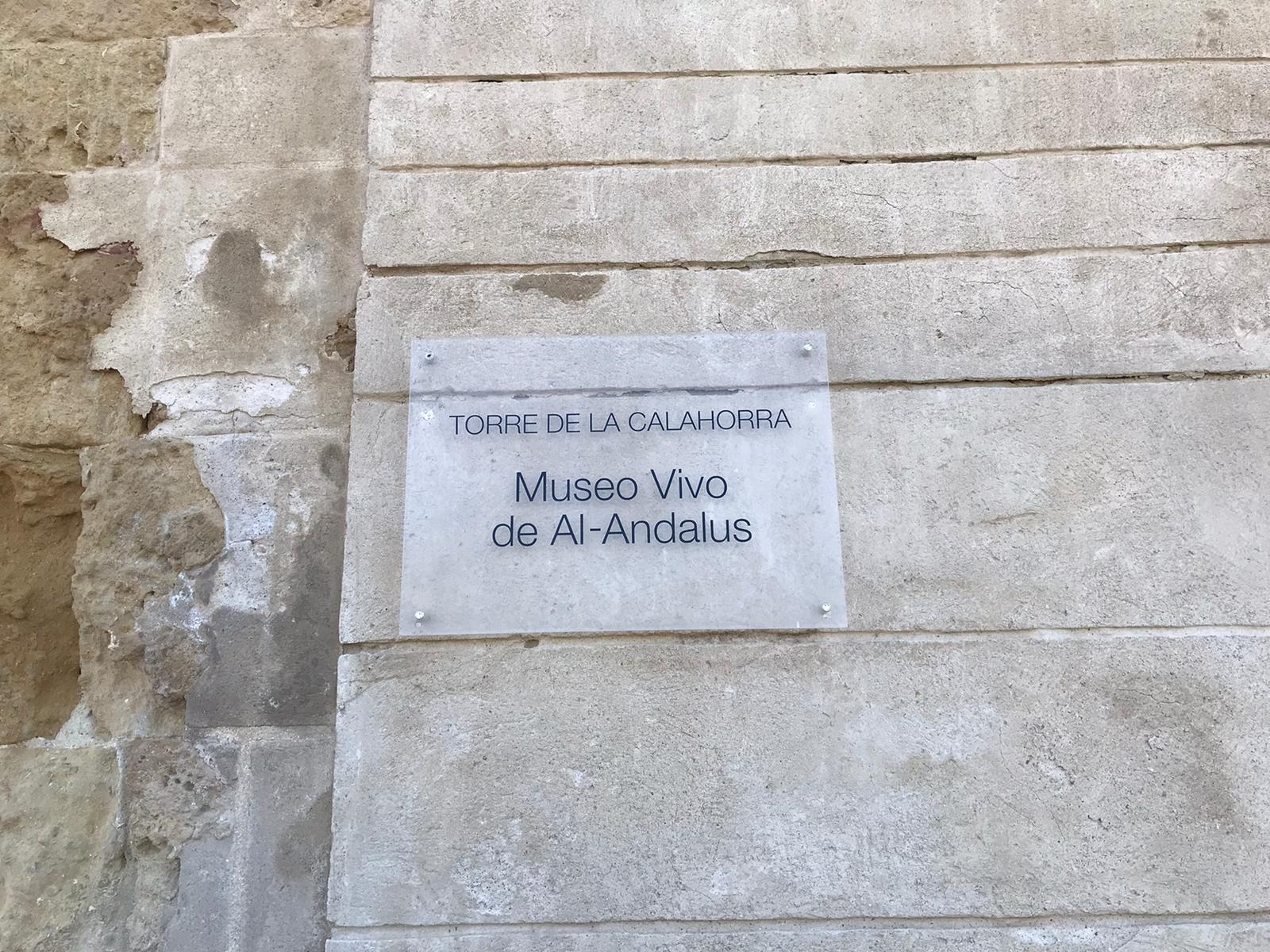

The Calahorra Tower (Torre de la Calahorra)

We return to Cordoba city and head to the Calahorra Tower. We park the car in a neighbouring street for free and enter the Tower. The Tower was built by the Muslims on the far side of the Roman Bridge on the other side of the River Guadalquivir (Wādī al-Kabīr) to prevent the city from being attacked. It thus served as a fortified gate.

Today, the Tower along with its impressive appearance and views of the old city serves as a museum. It features artifacts and documents of the rich Cordoban history which is characterised by the peaceful coexistence of Jews, Muslims, and Christians over centuries. It also presents the early height of science, culture, and engineering that gave Andalusia a leading position centuries ago. A multimedia show, which is available in English, makes the stories the museum has to tell an enjoyable experience. A model of the Great Mosque in its original state and a number of documents and pictures round off this informative journey through Cordoba’s history.

We exit the Tower and walk on the Roman Bridge over the River Guadalquivir towards the old city. The river is dirty and not navigable. If properly maintained, it has the potential to become a tourist attraction similar to the Thames. The bridge offers some good views of the Great Mosque and the old city.

Alcazar de los Reyes Cristianos

Our first stop after crossing the bridge is the Alcazar de los Reyes Cristianos (Castle of the Christian Kings), also known as the Alcazar of Córdoba, located next to the Guadalquivir River and near the Great Mosque. The fortress served as one of the primary residences of Isabella and Ferdinand who built it upon the ruins of a vast Muslim fort, inspired by Muslim principles of design.

It was from here they plotted and succeeded in taking the last remaining Muslim stronghold of Granada from the Nasrids. This is also the place where they welcomed Christopher Columbus who explained his plans to find a westbound sea route to India.

Sinagoga

Next, we walk to the Synagogue within the Jewish quarter of the old city which was built in 1315. It is one of only three synagogues throughout Spain and the only one in Andalusia. It is small and square, but very tall, probably to collect daylight from above the rooftops. Its walls are covered with rich white Islamic style decoration and Hebrew inscriptions.

Casa Andalusi

Next to the Synagogue is the Casa Andalusi, a house-museum which provides a glimpse into the Muslim Andalusian era. Inside, a cozy and cool courtyard welcomes visitors with the pleasant sound of water from its fountain and the greenery of the plants. It is also home to the Museo del Papel (Paper Museum), which features an interesting journey through the manufacturing process of paper manufacturing in the Cordoba Caliphate. There are also some handwritten verses of the Quran and some pages of a Fiqh text on display. Underneath the current house are typical elements of the houses from the Jewish Quarter, passageways that run under the buildings and reach beyond the city walls.

Siesta

It is now 3pm and we return to the hotel. Most restaurants are closed during late afternoon, as Siesta is common in Spain. Many tourist attractions also close at 2pm or 3pm, so it is best to start early.

Taj Mahal Restaurant and La Flor de Levante

Later in the evening, we visit the Taj Mahal Restaurant which is not far from our hotel. Qārī Ṣāḥib has been missing Indian food and I remembered this Indian restaurant from the Huma’s Travel Guide to Islamic Spain. The restaurant has a good meat and vegetarian menu and the food was good. The fresh Tandoori Naan deserves a special mention. Although alcohol bottles are sold, the owner is adamant that the meat is Halal and explains the local source.

As this restaurant is not within the old city or the tourist area, the price is reasonable. We also experience similar when we visit a really nice ice cream place, La Flor de Levante, thereafter.

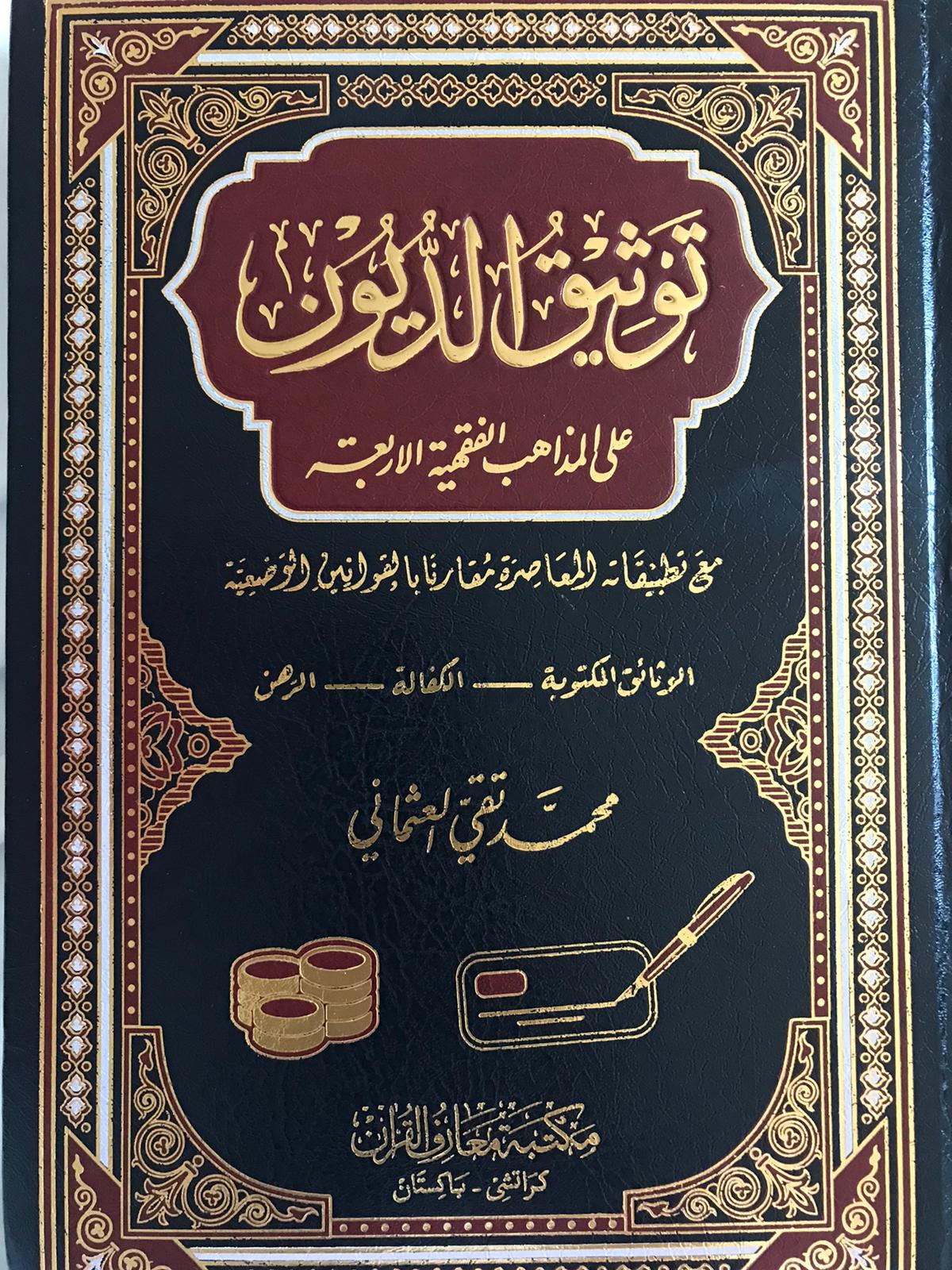

Later in the evening, I tweet, “I finished reading ‘Tawthīq al-Duyūn’ (توثيق الديون) by our respected Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani in the historic city of Cordoba (Qurṭubah) which was once a global centre of knowledge.” It is my habit to try and read a book and also do some writing while travelling although it is challenging when constantly on the move. Tawthīq al-Duyūn follows on from Mufti Ṣāḥib’s Fiqh al-Buyūʿ, which has received widespread acceptance.

Day 6 – Monday 26 July 2021

From Cordoba to Seville

Matalascañas Beach

We check out from our hotel in Cordoba at midday and travel towards Seville.

As most tourist attractions are closed on Monday throughout Spain, we decide to make most of the day by visiting the closest beach to Seville, in Matalascañas. The distance between Cordoba and Seville is 142km, which takes an hour and a half. The drive from Seville to Matalascañas takes another hour.

The Matalascañas Atlantic coast line is surrounded by Doñana National Park. The beach itself is 7 kms long. The mild Mediterranean climate, fine golden sand of the beachfront, mobile dunes, and clean water attract tourists throughout the year. We attempt to locate a quiet spot.

After enjoying the beach in Matalascañas, we return to Seville and check into Hotel Sevilla Centre at 6.30pm. It is evident that Seville is a very large and well-developed city.

Seville (Ishbīliyyah)

Seville is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous region of Andalusia and the province of Seville with its population exceeding 700,000. The Andalusian Parliament is based here. The city is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula. Known as Ishbīliyyah after the Islamic conquest in 711, Seville became the center of the independent Taifa of Seville following the collapse of the Caliphate of Cordoba in the early 11th century. It was then ruled by Almoravids (Al-Murābiṭūn) and Almohads (Al-Muwaḥḥidūn).

Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī (d. 622/1225) writes in Muʿjam al-Buldān (1:195) in reference to his era that there is no city in Al-Andalus greater than Seville. He also makes reference to the Cotton that is imported from Seville to other parts of Al-Andalus and the Maghreb. Even today, the large majority of cotton production is concentrated in Andalucía, especially in the provinces of Cadiz and Seville. Across the EU, Spain is the second largest producer of Cotton after Greece.

In 1248, Seville was incorporated to the Crown of Castile and its role diminished thereafter. However, by the 16th century, it became one of the largest cities in Western Europe due to its role as gateway of the Spanish Empire’s transatlantic trade.

Some scholars of Seville

Like other towns and cities of Al-Andalus, Seville also takes pride in many scholars and luminaries who lived there. They include:

- Imam Qāḍī Abū Bakr ibn al-ʿArabī al-Mālikī (d. 543/1148) who requires little introduction. He was born in Seville and also presided over the judiciary here. His commentaries on Sunan al-Tirmidhī and the Muwaṭṭaʾ along with his Aḥkām al-Quran and al-ʿAwāṣim are from among his notable published works. Recently, his book ‘Sirāj al-Murīdīn’ has been published from Morocco which is another unique book. He passed away in Fes, Morocco (Siyar, 20:203).

- Qāḍī Ibn al-ʿArabī al-Mālikī should not be confused with the controversial Sufi scholar, Shaykh Muḥyuddīn ibn ʿArabī al-Mursī al-Dimashqī (d. 638/1240), who is known as Shaykh al-Akbar among his supporters. He was born in Murcia, Spain and moved to Seville as an adolescent. Later he travelled across the Muslim world and passed away in Damascus. The ‘Ibn Arabi’ sculpture that exists in the Calahorra Tower museum in Cordoba is of him. Interestingly, he was a Ẓāhirī and on the subject of the number of Rakʿah of Tarāwīḥ Ṣalāh, he holds the view held by his ardent critic Shaykh al-Islam Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 728/1328), as outlined in my book ‘Al-Waḍāḥah fī al-Taṭawwuʿ bi al-Jamāʿah’. Scholars hold three views regarding Shaykh Ibn ʿArabī which I have detailed in ‘Aqwāl al-Jahābithah fī Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymiyyah’ and also ‘Irshād al-Qārī ilā Ikhtiyārāt Shaykhinā al-ʿAllāmah al-Muḥaddith Muḥammad Yūnus al-Jownfūrī’. Some reject him outright, whilst others affirm his credentials and a group prefers silence and abstention (tawaqquf) on the issue.

- Ḥāfiẓ ʿAbd al-Ḥaqq al-Ishbīlī (d. 581/1185) who grew up in Seville and later moved to Bijayah, Algeria (Siyar, 21:198). Ḥāfiẓ Dhahabī describes him as “Ḥāfiẓ of the Maghreb” (Siyar, 21:157). The great master of ḥadīth, Ḥāfiẓ Zaylaʿī (d. 762/1360) relies on his book “al-Aḥkām al-Kubrā” and frequently quotes from it in his famous Takhrīj work on the ḥadīths of Hidāyah, which is commonly and incorrectly known as Naṣb al-Rāyah. Ḥāfiẓ Zaylaʿī also relies on Imam Ibn al-Qaṭṭān al-Fāsī’s (d. 628/1231) “al-Wahm wa al-Īhām” which highlights errors within “al-Aḥkām”. It is in this context Shaykh Muḥammad ʿAwwāmah (b. 1358/1940) writes, “Were it not for the citations of Ibn al-Qaṭṭān, Ibn Daqīq al-ʿĪd and Ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī in Naṣb al-Rāyah, the book would have lost half its significance and academic worth”.

Jaipur Palace

After checking into the hotel and freshening up, we decide to search for an Indian Halal restaurant. A google search takes us to the Taj Mahal restaurant where the Muslim worker confirms that the food is Halal. We feel uncomfortable because in addition to the alcohol, it is filled with Hindu idols and imagery. The workers confirm that the owner is a Hindu.

We head to Jaipur Palace in the centre of the city next to the Metropol Parasol, an attraction we plan to visit tomorrow morning. The food at Jaipur Palace is of decent quality, although it serves alcohol like most Halal restaurants in this region.

Day 7 – Tuesday 27 July 2021

The Muezzin would ascend the 342ft minaret on a horse in Seville

Metropol Parasol (Las Setas) and Antiquarium

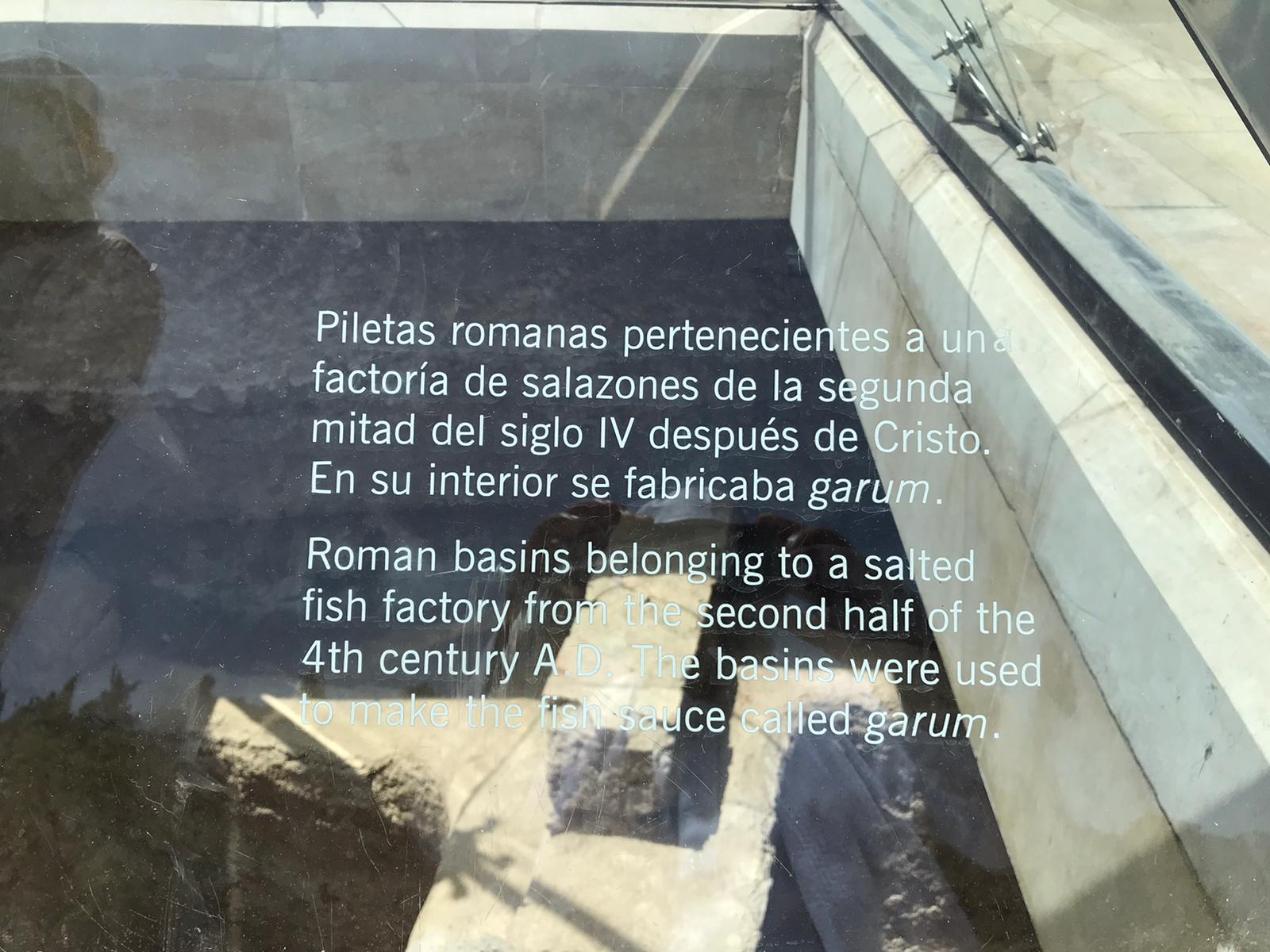

Our time is limited in Seville so we checkout after breakfast and head to the Metropol Parasol, which also houses the Antiquarium archaeological museum on the underground level. The museum was created to allow people to visit the outstanding archaeological Romana and Moorish remains that were found during the early excavations for the realisation of the Metropol Parasol.

The Metropol Parasol is a wooden structure located at La Encarnación square, in the old quarter of Seville, Spain. It was designed by the German architect Jürgen Mayer and completed in April 2011. It has dimensions of 150 by 70 metres (490 by 230 ft) and an approximate height of 26 metres (85 ft) and is the largest wooden structure in the world. The structure consists of six parasols in the form of giant mushrooms (‘Las setas’ in Spanish), whose design is inspired by the vaults of the Cathedral of Seville and the Ficus trees in the nearby Plaza de Cristo de Burgos. Metropol Parasol is organised in four levels. The underground level (Level 0) houses the Antiquarium as mentioned above. Level 1 (street level) is the Central Market. The roof of Level 1 is the surface of the open-air public plaza, shaded by the wooden parasols above and designed for public events. Levels 2 and 3 are the two stages of the panoramic terraces (including a restaurant) which offer some excellent views of the city.

Due to limited time, we do not visit the inside of the museum. However, we ascend to the panoramic terraces and walk through the mushrooms.

Shaykh Muhammad Idreesi

Our next stop at 12.30pm is the Alcazar, the Royal Palace of Seville. Here, we meet Shaykh Muhammad Idreesi who has agreed to give us a tour. He advises us to park our cars in the nearby ‘Parking Roma’ car park.

Shaykh Muhammad Idreesi studied in Dewsbury Markaz for eight years and is the first graduate scholar of a Dars Niẓāmī system in modern-day Spain. His mother is a Spanish Muslim whilst his father is Moroccan. Our respected Mawlānā Yūsuf Darwān Ṣāḥib of Dewsbury kindly provided me with his contact details and informed him of my visit. He greets us and gives us an insight into the history of Seville, highlighting that Seville was the first capital of Al-Andalus when ʿAbd al-Azīz ibn Musā ibn Nuṣayr (d. 97/716) chose the town of Seville as his capital city in approximately 711 CE. Today, there are only six Masjids and Musallas in the city, although there are 15,000 Muslims residing in Seville city and 30,000 in Seville province.

Alcazar (Al-Qaṣr) of Seville

Shaykh Muhammad Idreesi first takes us to the Alcazar, the Royal Palace of Seville, which is the most famous attraction in Seville. It is made up of diverse palaces and gardens designed during different historical periods. The Christian king Fernando III moved into the Alcazar when he captured Seville in 1248, and several later monarchs used it as their main residence. The palace is still in use today by the Spanish King, making it the oldest palace in use in Europe. The Encyclopaedia Britannica states:

“The finest survival from the Moorish period is the Alcázar Palace, which lies near the cathedral. The Alcázar was begun in 1181 under the Almohads but was continued under the Christians; like the cathedral, it exhibits both Moorish and Gothic stylistic features.”

Shaykh Idreesi explains that although some parts of the Palace were built during Christian rule, the builders were Muslims. This explains the inscription on the walls, “Wa-la Ghalib illa Allah” (There is no Victor but Allah). In addition, he explains that the trees planted in a lower patio and the water stream all symbolise paradise, as per the verse of the Quran (69:23):

قطوفها دانية

Its fruits are close.

along with the following verse (2:25):

جنات تجري من تحتها الأنهار

(Gardens beneath which the rivers flow).

Cathedral and La Giralda (Minaret)

At 2.30pm, we walk towards Seville Cathedral opposite the Alcazar. It is the largest gothic cathedral across the world. It was constructed between 1402 and 1506 on the site of the city’s Great Mosque, which during Muslim rule was the second largest mosque in Al-Andalus after the Cordoba Mosque. There are no remains of the mosque except the minaret (La Giralda) which was incorporated as the bell tower of the cathedral and the ablution area outside.

We enter the cathedral and view the treasure trove, the tomb of Christopher Columbus and the royal chapel.

We also walk to the top of the minaret (La Giralda), which is 104m (342ft) high. Built in 1198, it was the tallest minaret and tower worldwide. It does not have stairs to ascend. Instead, it has 35 wide ramps enabling the Muezzin to ascend on a horse. Walking to the top is a unique experience reminding a person of the glorious past and providing a beautiful panoramic view of the city. The minaret has surfaces almost entirely covered with beautiful yellow brick and stone panelling of Moorish design, and it has survived several earthquakes.

As we descend into the cathedral, I ask Shaykh Idreesi if this is the Masjid where the likes of Imam Abū Bakr ibn al-ʿArabī studied and taught. He replies in the affirmative. I also ask him about the graves of the scholars who passed away in Spain. He explains that the graves of Muslim scholars and luminaries are not known. All signs were obliterated.

We exit the building and view the ablution area outdoors. Thereafter, we exit the complex and observe the following engraved on the doors: الملك لله والبقاء لله.

Tower of the Gold (Torre del Oro) – Burj al-Dhahab

We collect our cars at 4pm and are now heading to the Madrasah Al-Andalusia, run by Shaykh Muḥammad Idreesi. On our route, we go past the Torre del Oro, the Tower of the Gold, a tower from the 12th century located on the Guadalquivir River. At the time, it was part of the Moorish city wall of Seville and once served as a storage place for gold and also as a prison. It now houses a small maritime museum. The Encyclopaedia Britannica aptly describes it as “A decagonal brick tower, the Torre del Oro, once part of the Alcazar’s outer fortifications, remains a striking feature of the riverbank.”

River Guadalquivir (Wādī al-Kabīr)

The Guadalquivir is the fifth longest river in the Iberian Peninsula and the second longest river with its entire length in Spain. It is the only navigable river in Spain today. Currently, it is navigable from the Cadiz to Seville, but in Roman times it was navigable to Cordoba. As mentioned above, the river is in a poor condition in Cordoba. However, in Seville it is in a good condition and offers boat tours and water sports.

The river has played a leading role in many of the city’s historic moments. Sieges, defences and conquests have been fought on its waters, and exploits and crossings have been forged from its shores. In October 844 (230 hijrī), the Vikings used this river to raid Seville. Shaykh Muḥammad Idreesi suggests that the Vikings introduced cheese in Seville.

More recently, in the 16th century, the city was the mercantile centre of the western world as mentioned above, and this river was the main maritime route for Atlantic traffic.

The double walls of Seville

As we head to the Madrasah Al-Andalusia in the Macarena neighbourhood of Seville, we notice some old walls. These are a series of defensive walls surrounding the old town of Seville. The city has been surrounded by walls since the Roman period, and they were maintained and modified throughout the subsequent Visigoth, Islamic and finally Castilian periods. The walls remained intact until the 19th century, when they were partially demolished after the revolution of 1868. Some parts of the walls still exist, especially around the Alcazar of Seville and some curtain walls in Macarena.

The double walls are of particular interest. This doubling of the walled enclosure was a strategic move that took place between the 11th century and 12th century to strengthen the defence of the city. Attackers had to cross several gates and courtyards before entering the city. From the heights of the inner wall, defenders fired arrows and poured boiling oil on the attackers. This explains how the Muslims were able to resist the Christian siege between July 1247 and 28 November 1248. It was hunger in the end which forced the Muslims to surrender.

Mr Kebab Damasco

At 4.30pm, we arrive in Macarena and first visit a local Halal take-away Mr Kebab Damasco with Shaykh Idreesi. The food here is good notwithstanding the delays.

Madrasah Al-Andalusia

Our final stop in Seville is the Madrasah Al-Andalusia run by Shaykh Idreesi. The institute serves 200 students on site with primary Islamic education, the equivalent of a Maktab in the UK. In addition, the institute has also started a programme to create scholars (Alim course) in Spanish. Due to Covid-19, the classes have been running online for a year and some 150 students have enrolled from 17 countries. This is significant because English is rarely understood in countries where Spanish is prevalent such as South America.

Shaykh Idreesi explains that there are many challenges in Spain with the Muslims who are first generation, many of whom have come from Arab countries where Islamic education is provided for free. There also some parents who cannot afford the nominal fees.

It is pleasing to learn that Ummah Welfare Trust (UWT) is funding the teachers of the institute, something I was unaware of. It is holidays at the moment, so there are no classes running. Nevertheless, we visit the classes and perform Ṣalāh here. The institute is currently in a rented facility. May Allah accept the efforts of Shaykh Idreesi and all the teachers and students.

Divisions within the Ummah

During the day, some interesting discussions take place with Shaykh Idreesi. We reflect on the fall of Islamic Spain and how divisions and conflicts among Muslims were a major cause and contrasted this with the divisions within the Ummah today. I cite the example of Sierra Leone which I visited a few weeks ago, where there is a huge challenge of preserving the faith of people combined with acute levels of poverty. Despite this, the country has not been spared from the divisions within the Tabligh movement. Only if the seniors understood and appreciate the ramifications of the division on the ground in such countries.

From Seville to La Línea de la Concepción on the Spain-Gibraltar border

Shaykh Idreesi bids us farewell at 6.15pm as we start the 200km journey south towards Gibraltar. The beautiful scenery begins some 20 minutes before arriving.

At 8pm, we arrive at the ‘Ohtels Campo De Gibraltar’ hotel in the Spanish town of La Línea de la Concepción which lies on the border of Gibraltar. Gibraltar is relatively expensive so we decide to stay here for two nights. Many people who work in Gibraltar prefer to live in Spain because of cheaper living costs. Our hotel is advertised as four star, but at best it is three star. One of the things I notice across the hotels of Spain is the prevalence of the Bidet in toilets which I understand is common in Catholic countries, similar to Muslim countries.

Day 8 – Wednesday 28 July 2021

Jabal Ṭāriq (Gibraltar)

Gibraltar

Gibraltar is a small British Overseas Territory on Spain’s south coast. It has an area of 2.6 square miles. The beautiful landscape is dominated by the Rock of Gibraltar, a 426m-high limestone ridge, at the foot of which is a densely populated town, home to over 32,000 people, primarily Gibraltarians. It is named after Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād (d. 101/720) who commanded the Muslim army here on 5 Rajab 92 Hijrī (29 April 711 CE). It was ruled by the Muslims during the Middle Ages, and thereafter by Spain.

In 1704, Anglo-Dutch forces captured Gibraltar from Spain during the War of the Spanish Succession on behalf of the Habsburg claim to the Spanish throne. The territory was ceded to Great Britain in perpetuity under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. During the Napoleonic Wars and World War II, it was an important base for the Royal Navy as it controlled the entrance and exit to the Mediterranean Sea, the Strait of Gibraltar, which is only 8.9 miles wide at this naval choke point. It remains strategically important, with half the world’s seaborne trade passing through the strait. The sovereignty of Gibraltar remains contentious because Spain asserts a claim to it. Gibraltarians rejected proposals for Spanish sovereignty in a 1967 referendum and, in a 2002 referendum, the idea of shared sovereignty was also rejected.

Entry into Gibraltar

We head to the Spain-Gibraltar border crossing at 10.30am which is only several hundred yards away. Gibraltar is very scenic. It is possible to enter Gibraltar on foot and also in the car. Entering on foot is quicker and one can use the bus to travel in the small territory. We opt for the car for convenience. It takes us 20 minutes to cross over and we are somewhat relieved to be in a British territory where English is spoken and understood and where the British pound can be used.

Rapid COVID-19 Testing Service at Gibraltar Airport

As soon as you enter Gibraltar, the first attraction is the four-lane Winston Churchill Boulevard, the main road leading into and out of Gibraltar which cuts across the runway. The traffic on the road is closed during every take off and landing.

Gibraltar Airport offers a rapid Covid-19 testing service which can be booked in advance. A test is necessary within 72 hours prior to returning to the UK, so we proceed first to the test booth outside the terminal. The service is excellent and the results are emailed within 30 minutes of the test. The cost is £30. The certificate is signed by Dr Sohail Bhatti, the Director of Public Health of Gibraltar. Dr Sohail is known to us because he worked in public health in Lancashire for many years. Later in the day, we read in the newspaper that he is leaving his post and returning to England.

Cable Car

The Gibraltar Cable Car is our next stop. It is located near the southern end of Main Street, next to Alameda Gardens. The journey to the top of the rock only takes 6 minutes, offering some of the most scenic views of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean.

From the top, both sides of the rock are visible.

Caution must be exercised with the monkeys at the top of the rock, and backpacks and rucksacks must be held in front. There is also a nature reserve at the top of the rock, for which there is an additional cost. Generally, it is more advantageous to use Pounds here than Euros.

We take the return journey on the cable car and collect our cars from the car park.

From the Cable Car, we continue our tour of Gibraltar and pass a mountain from which water is gushing down, reminding us of the verse of the Qur’an (2:74):

وَإِنَّ مِنَ ٱلْحِجَارَةِ لَمَا يَتَفَجَّرُ مِنْهُ ٱلْأَنْهَٰرُ، وَإِنَّ مِنْهَا لَمَا يَشَّقَّقُ فَيَخْرُجُ مِنْهُ ٱلْمَآءُ

And indeed there are some stones from which rivers burst forth, and indeed there are some that split open and water comes out.

King Fahad Mosque

Next, we visit the Ibrahim-al-Ibrahim Mosque, also known as the King Fahd bin Abdulaziz al-Saud Mosque, which was inaugurated in 1997. It took two years to build at a cost of £5 million. The mosque is perfectly located on the southern tip of Gibraltar and is the southernmost mosque in continental Europe. There is a lighthouse nearby and also a playground for children.

We perform Ẓuhr Ṣalāh here. There are only a few worshippers. We understand that Muslims in Gibraltar number approximately 1000.

There is also a small mosque in the centre of the territory named after Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād.

Dolphin Watching Boat Trip

At 3.30pm, we take a 90-minute boat trip in the strait area for dolphin watching. Dolphins are very intelligent and sociable animals, spending almost all of their time in the company of others of their species. Dolphins work together to gather food, help each other to sleep, to give birth or to assist when another dolphin is ill or injured. They can be found around the coast of Gibraltar where they feed on sardines, herring, squid, anchovies and flying fish and have been known to dive to a depth of about 280 metres. There is a difference of opinion among Ḥanafī jurists whether dolphin is a fish or not from a jurisprudential perspective, because scientifically it is a mammal.

Roy’s Fish and Chips

Following the boat ride, we drive to the Roy’s Fish and Chips in the town centre because the fish and chips shop outside King Fahad Mosque on the waterfront is closed. The owner of Roy’s Fish and Chips is English and acutely aware of our dietary requirements. She confirms that the batter is alcohol free and the fish is fried separately.

Outside the fish and chips shop is the ‘Mama Lulus Ice Cream’ shop. The owner is proud to be British and informs us with price that he imports cream from South England for his ice cream. The ice-cream is worth buying. He has Irish roots and his ancestors have resided in Gibraltar for 285 years. He confirms that most Gibraltarians want to remain with Britain and that the Spanish are merely playing politics.

Gibraltar is a very expensive place to live in. The property prices are high. A visit to the territory, however, would be incomplete without visiting the Morrisons, where the prices are reasonable. Fuel is cheaper in Gibraltar than Spain so it is worth filling the tank.

Gibraltar is a beautiful blend of British life, sprinkled with Spanish flair and gently simmered in the Mediterranean sunshine. The drive around this small territory is amazing. It is simply from the signs of Allah and should not be missed by anyone travelling to South Spain.

Golden Palace Indian Continental Restaurant

We return to our hotel in Spain. Later in the evening, Qārī Ṣāḥib and I go for a ride in La Línea de la Concepción which has many beaches. The evening ends with a delicious meal at the Golden Palace Indian Continental Restaurant, where Fresh Bhindī (Okra) and Prawns are served with fresh Tandoori Naan and Roti. A delicious meal to end the day.

Day 9 – Thursday 29 July 2021

Return home

Another Covid-19 test

Today is our final day in Spain. Some of my cousins are currently in Saudi Arabia and I am thinking of joining them. The fit to fly tests in the UK are expensive and a hassle, so I decide to return to Gibraltar Airport, this time on foot, and take another test, enabling me to travel to Saudi Arabia on Saturday should I decide to do so. Crossing the border on foot is much quicker.

King Abdul Aziz Mosque, Marbella

We depart from La Línea de la Concepción and start the journey to Malaga Airport. On the way, we stop at the King Abdul Aziz Mosque in Marbella.

Marbella is a city and resort area on southern Spain’s Costa del Sol. The Sierra Blanca Mountains are the backdrop to 27 km of sandy Mediterranean beaches, villas, hotels, and golf courses. West of Marbella town, the Golden Mile of prestigious nightclubs and coastal estates leads to Puerto Banús marina, filled with luxury yachts, making it a popular holiday destination for rich Arabs.

The King Abdul Aziz Mosque was built in 1981 and is one of the first Spanish mosques built in modern Spain. We perform Ṣalāh here and head to Malaga Airport, as we do not have time to visit the city.

Ronda

My dear friend Shaykh Ebrahim Bham of South Africa messaged me earlier that we should consider visiting Ronda because of its history, adding that there was an agreement among its Khānqas (Sufi lodges) of rotating the Adhkār in a way that Dhikr would take place throughout the 24 hours of the day and night. The poet Abū al-Baqā al-Rundi (d. 684/1285) was from here whose couplets were cited above. ʿAbbās ibn Firnās (d. 274/887), the father of aviation, was also born here, as mentioned above.

Ronda is 62km from Marbella and 102km west of Malaga. We do not have the time to visit it. The Huma’s travel guide to Islamic Spain has a section on Ronda for those who are interested.

Morocco

A place we had intended to visit during this journey was Morocco. However, there are currently no ferries between Spain and Morocco. Previously, ferries would travel from both Algeciras and Tarifa to Tangier in Morocco.

Return journey home

We arrive at Malaga Airport at 2.45pm, return our rental cars and check in for the 17.50 Ryan Air flight to Manchester. Prior to this, we completed the Passenger Locator Forms and also booked the day 2 tests.

After security, we sit near the shopping areas thinking that the boarding gate is only a few minutes away. We do not realise that there is passport control before the boarding gate and when we arrive here, there is a long queue. Perhaps, this is a result of Brexit. We reach the boarding gate 15 minutes prior to the departure time. Some 25 passengers also arrive after us. However, Ryan Air has closed the gates and do not allow us to board.

We are left with no choice but to book new tickets to Edinburgh, where we arrive shortly before midnight. New passenger locator forms are completed. My dear friend Mawlānā Wasim Amin and Mawlānā Mubassir, the Imam at Glasgow Markaz, kindly bring food for us at Edinburgh Airport and also drop us to Blackburn. May Allah reward them for their support at such short notice. One has to be prepared for all circumstances when travelling.

Concluding Thoughts